I bow to better terminology: mass-market is much more accurate than open-enrollment. Students in my mass-market college are terrified of (if they're ever heard it) Liberal Arts. Most will describe themselves as undecided, pending, general studies, or gettin' my basics. When I urge them to declare themselves Liberal Arts majors, a look of horror passes over their faces. Of course, living in the Texas Panhandle, any mention of Liberal is akin to blasphemy. Over and over and over, students I encounter in my mass-market institution have no idea what Liberal Arts means. If this be (fair & balanced) frustration, so be it.

[CHE]

Liberal Arts and the Mass Market

By JOHN A. FLOWER

The millions of first-generation undergraduates now in mass-market institutions, like regional state universities and community colleges, have had little to no exposure to the power of thought within the liberal arts. They have no great interest in the life of the mind. The lack of experience on the part of these students in how to handle ideas -- as contrasted to the immediate, hedonistic response of their senses -- is both a national disgrace and a disaster. The inherent contradictions are highlighted by the billions of dollars spent on their "education'' in the public schools. These students desperately need the influence of the proven great thinkers of the past. They are not getting it.

This inherited thought cannot be presented to these college students in the same way that worked in the past for the select undergraduate students in privileged campus enclaves. As contrasted to yesteryear's full-time students, vast numbers of today's students at mass-market campuses are supporting themselves with outside jobs. They are enrolled part time and cannot fit themselves into the conventional and conveniently structured (convenient for professors) schedules of academic life.

Unfortunately, liberal-arts faculties in mass-market institutions have failed to understand the need to adjust their styles and methods of teaching to accommodate these everyday students who come from tract houses in the suburbs, trailer parks, walk-ups in urban areas, and public-housing projects. There are few books on the shelves of the homes where millions of our citizens live. While mounds of information can be downloaded from computers either at home or at workstations at school, surfing the Internet is no substitute for reading Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics and then discussing it with a sensitive and responsive member of the faculty.

To connect these students to the power of ideas and to accommodate to their needs should be the primary mission of the liberal-arts faculty members of mass-market campuses. But this has not happened. Current and practical student needs have altered the missions of these campuses to exalted trade schools. The forces motivating most humanities faculties and those motivating students on these campuses are at odds.

I believe we must teach liberal arts to every one of the millions of current college students. For the most part (excepting upper-tier private colleges and not always those), I believe faculties are not doing a very good job of this kind of teaching. What do I think would help? It would help if humanities professors understood the motivations and ways of thinking of their students from the mass market. The differences in thinking between these professors and their students inhibit the transfer of vitally important concepts and ideas. Thus, liberal-arts and humanities professors periodically should get themselves out into the marketplace and onto the street in order to learn how to communicate better with their students. At regular intervals they should venture beyond their protected positions behind lecterns, in seminar rooms, or in library carrels, where too many of them churn out never-ending streams of papers and reports that have little or no significance and for all practical purposes are read by no one.

How to do this? The academic year plus the summer, which together have many more periods of recess than businesses and public organizations do, afford opportunities for professors of the liberal arts to do different things. Too many of them simply mow their lawns and paint their houses. A creative liaison between business and university departments (perhaps encouraged by some modest foundation funding) could provide opportunities for liberal-arts professors to experience what is going on in the worlds outside their academic departments. How wonderful it would be for a philosophy professor to have an internship at the City Council. What a fine opportunity it would be for a language professor to have an internship at the welfare office. Think how a history professor could benefit from identifying with an emerging business, or with an office in venture capital. This is what is needed in many hundreds of liberal-arts and humanities units serving the mass ma-ket of students. It has far more importance than sitting in shared-governance-committee meetings.

Teaching the liberal arts on mass-market campuses cannot be approached in the same ways that are effective in elite colleges with selected students from privileged homes providing well-prepared backgrounds -- where their conditioning makes an approach to humanities subjects much easier for the teacher. In mass-market institutions where students' aims are, first, to train for jobs and only second to become educated, teachers must create an intellectual environment where humanities subjects can be credibly approached.

John A. Flower is former president of Cleveland State University. This article is excerpted from his Downstairs Upstairs: The Changed Spirit and Face of College Life in America, published by University of Akron Press. Copyright © 2003 by John A. Flower.

Copyright © 2003 by The Chronicle of Higher Education

Sunday, November 30, 2003

Mass-Market Institutions?

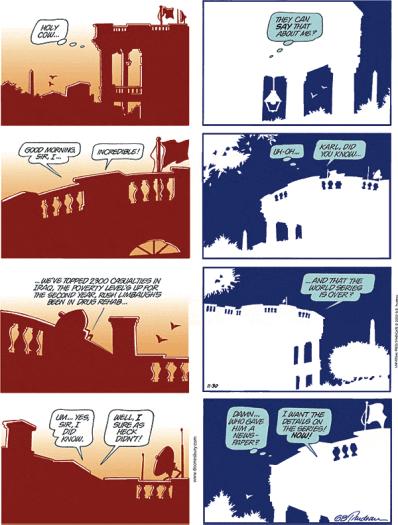

Garry Trudeau Strikes Again!

The Amarillo Fishwrap doesn't carry the Sunday issue of Doonesbury. Instead, the Fishwrap just bought out Opus by Berke Breathed. Opus was a character in Bloom County which Breathed stopped doing several years ago. This latest stip just is NOT funny. Instead of Doonesbury, the Fishwrap opts for a second-rate version of Bloom County. If this be (fair & balanced) comic-rage, so be it!

Friday, November 28, 2003

TXE?

I dunno. Texas English? Spanglish? Ebonics? It sounds like rock'n roll to me (pace Billy Joel). If this is (fair & balanced) linguistics, so be it.

[x NYTimes]

Scholars of Twang Track All the 'Y'Alls' in Texas

By RALPH BLUMENTHAL

COLLEGE STATION, Tex. — "Are yew jus' tryin' to git me to talk, is that the ah-deah?"

That was the idea. John O. Greer, an architecture teacher at Texas A&M University, sat at his dining table between two interrogators and their tape recorder. They had precisely 258 questions for him. But it waddn what he said that interested them most. It was how he said it.

Those responses, part of an ambitious National Geographic Society survey of Texas speech, with its "y'alls," "might-coulds" and "fixin' to's," are helping language investigators throw a scientific light on a mythologized and sometimes ridiculed mainstay of Americana: the Texas twang.

Among the unexpected findings, said Guy Bailey, a linguistics professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio and a leading scholar in the studies with his wife, Jan Tillery, is that in Texas more than elsewhere, how you talk says a lot about how you feel about your home state.

"Those who think Texas is a good place to live adopt the flat `I' — it's like the badge of Texas," said Dr. Bailey, 53, provost and executive vice president of the university and a transplanted Alabamian married to a Lubbock native, also 53.

So if you love Texas, they say, be fixin' to say "naht" for "night," "rahd" for "ride" and "raht" for "right."

And by all means say "all" for "oil."

In addition to quickly becoming enamored of Western garb like cowboy boots and hats, big-buckled belts, western shirts and vests, newcomers to the state — and there are a lot of them — are especially likely to adopt the lingo pronto.

At the same time, the speech of rural and urban Texans is diverging, Dr. Bailey said. Texans in Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth and San Antonio are sounding more like other Americans and less like their fellow Texans in Iraan, Red Lick or Old Glory.

Indeed, Dr. Tillery and Dr. Bailey wrote in a recent paper called "Texas English," a new dialect of Southern American English may be emerging on the West Texas plains. It is not what a linguist might expect, they wrote, "but this is Texas, and things are just different here."

The changes are being tracked by researchers for the two San Antonio linguists, who are working with scholars from Oklahoma State University and West Texas A&M in Canyon, outside Amarillo, under the sponsorship of the National Geographic Society. They divided Texas into 116 squares and are interviewing four native Texans spanning four age groups— from the 20's to the 80's, in each.

As part of the latest effort, two master's students in linguistics from the University of North Texas at Denton, Amanda Aguilar, 24, and Brooke Earheardt, 23, arranged recently to record Mr. Greer, 70, as he responded to an exhaustive 31-page questionnaire.

Ms. Aguilar first probed some of Mr. Greer's attitudes toward Texas. Was it a barren state?

"It's in the ahs of the beholder," responded Mr. Greer, who was born in Port Arthur. The state, he said, was "dee-vahded, you kin almost draw a lahn."

Was it a progressive state?

"Compared to who?" he said. "Califohnia? Baghdad? Ah'd have to say Texas is a progressive state."

Distinctive?

"Most are distinctive in their own way," he said, smiling, "with the possible exception of Ah-wah." (That was Iowa.)

Next Ms. Aguilar quizzed Mr. Greer on a lexicon of Texas words and phrases. Had he ever heard the expression "y'all?"

Of course. "Ah think `you' sometimes just duddn't work bah itself."

Could you use it for just one person?

"Ah would trah to confahn it to the plural," he said. "It's just like `youse guys.' "

Had he heard "fixin' to?"

Of course again. " `Ahma' often goes with it," he said. "Ahma fixin' to go."

The questions and Mr. Greer's answers kept coming. A dragonfly? That's a "miskeeta hahk." A wishbone was a "pulleybone." A cowboy's rope was a lasso or a lariat, or just a "ropin' rope." A drought was worse than a "drah spell"; no rain, or "it haddn for a long tahm." You wait "for" a friend who hadn't shown up, but you wait "on" someone who is nearby and delayed, perhaps upstairs putting on makeup.

Afterward, Ms. Aguilar and Ms. Earheardt said that Mr. Greer, though white, employed some noticeable African-American and Deep South speech patterns. There were also Spanish influences, common in Texas, where Spanish was widely spoken for nearly a hundred years before English.

Dr. Tillery and Dr. Bailey warned that it was possible to exaggerate the distinctiveness of Texas English because the state loomed so large in the popular imagination. Few speech elements here do not also appear elsewhere.

"Nevertheless," they wrote in their paper on Texas English, "in its mix of elements both from various dialects of English and from other languages, TXE is in fact somewhat different from other closely related varieties."

Perhaps the most striking finding, Dr. Tillery said, was the spread of the humble "y'all," ubiquitous in Texas as throughout the South. Y'all, once "you all" but now commonly reduced to a single word, sometimes even spelled "yall," is taking the country by storm, the couple reported in an article written with Tom Wikle of Oklahoma State University and published in 2000 in the Journal of English Linguistics. No one other word, it turns out, can do the job.

"Y'all" and "fixin' to" were also spreading fast among newcomers within the state, they said, particularly those who regard Texas fondly. Use of the flat `I,' they found, also correlated strikingly to a favorable view of Texas.

But they found some curious anomalies, as well.

One traditional feature of Texas and Southern speech — pronouncing the word "pen" like "pin," known as the pen/pin merger — is disappearing in the big Texas cities, while remaining common in rural areas, Dr. Tillery said. Texans in the prairie may shell out "tin cints," but not their metropolitan brethren.

Urban Texas is abandoning the "y" sound after "n," "d" and "t," exchanging dipthongs for monophthongs. So folks in the cities read a "noospaper" — what their rural counterparts call a "nyewspaper." They'll hum a "tyewn" on the range, a "toon" in Houston. The upgliding dipthong, too, is an endangered species in the cities, where a country "dawg" is just a dog.

Why city Texans, more than country folk, should disdain to write with a "pin" is not clear, although it seems that some pronunciations carry a stigma of unsophistication while others do not.

It was such mixed patterns that suggested the emergence of a new dialect on the West Texas plains, Dr. Tillery said.

Other idiosyncrasies have all but vanished over time. Texans for the most part no longer pray to the "Lard," replacing the "o" with an "a," or "warsh" their clothes. How the interloping "r" crept in remains an especially intriguing question, Dr. Bailey said. Trying to trace the peculiarity, he asked Texans to name the capital of the United States, often drawing the unhelpful answer "Austin."

The opposite syndrome, known as r-lessness, which renders "four" as "foah" in Texas and elsewhere, is easier to trace, Dr. Bailey said. In the early days of the republic, plantation owners sent their children to England for schooling. "They came back without the `r,' " he said.

"The parents were saying, listen to this, this is something we have to have, so we'll all become r-less," he said. The craze went down the East Coast from Boston to Virginia (skipping Philadelphia, for some reason) and migrating selectively around the country.

Other common Texas locutions that replace an "s" with a "d" — "bidness" for "business," "waddn" for "wasn't" — are simply matters of mechanical efficiency, Dr. Bailey said. "With `n' and `d' the tongue stays in the same position," he said. "It's ease of articulation."

So even "fixin' to" becomes "fidden to" or "fith'n to." And fixin' to — where did that come from, anyway?

"Who knows?" Dr. Bailey said.

Copyright © 2003 The New York Times Company

Wednesday, November 26, 2003

Daffinitions

Thanks to Tom Terrific of Madison, WI, here are some funny daffinitions for your holiday delight. If this be (fair & balanced) lexicography, so be it!

The Washington Post publishes a yearly contest in which readers are asked to supply alternate meanings for various words. These are the 2002 winners:

1. Coffee (n.), a person who is coughed upon.

2. Flabbergasted (adj.), appalled over how much weight you have gained.

3. Abdicate (v.), to give up all hope of ever having a flat stomach.

4. Esplanade (v.), to attempt an explanation while drunk.

5. Willy-nilly (adj.), impotent.

6. Negligent (adj.), describes a condition in which you absent-mindedly answer the door in your nightgown.

7. Lymph (v.), to walk with a lisp.

8. Gargoyle (n.), an olive-flavored mouthwash.

9. Flatulence (n.) the emergency vehicle that picks you up after you are run over by a steamroller.

10. Balderdash (n.), a rapidly receding hairline.

11. Testicle (n.), a humorous question on an exam.

12. Rectitude (n.), the formal, dignified demeanor assumed by a proctologist immediately before he examines you.

13. Oyster (n.), a person who sprinkles his conversation with Yiddish expressions.

14. Pokemon (n), A Jamaican proctologist.

15. Frisbeetarianism (n.), The belief that, when you die, your Soul goes up on the roof and gets stuck there.

16. Circumvent (n.), the opening in the front of boxer shorts.

Joseph Epstein's Meditation On Fatherhood

Oh, my pa-pa, to me he was so wonderful

Oh, my pa-pa, to me he was so good

No one could be, so gentle and so lovable

Oh, my pa-pa, he always understood.

If this be (fair & balanced) sentimentality, so be it.

[x Commentary]

Oh Dad, Dear Dad

by Joseph Epstein

November 2003

IT WILL It will soon be five years since my father died, leaving me, at a mere sixty-two, orphaned. He was ninety-one when he died, in his sleep, in his own apartment in Chicago. Such was the relentlessness of his vigor that, until his last year, I referred to him behind his back as the Energizer Bunny: he just kept going. I used to joke—half-joke is closer to it—about “the vague possibility” that he would pre-decease me. Now he has done it, and his absence, even today, takes getting used to.

When an aged parent dies, one’s feelings are greatly mixed. I was relieved that my father had what seems to have been an easeful death. In truth, I was also relieved at not having to worry about him any longer (though, apart from running certain errands and keeping his checkbook in the last few years of his life, he really gave my wife and me very little to worry about). But with him dead, I have been made acutely conscious that I am next in line for the guillotine: C’est, as Pascal would have it, la condition humaine.

Now that my father is gone, many questions will never be answered. Not long before he died I was driving him to his accountant’s office and, without any transition, he said, “I wanted a third child, but your mother wasn’t interested.” This was the first I had heard about it. He was never a very engaged parent, certainly not by the full-court-press standards of today. Having had two sons—me and my younger brother—had he, I suddenly wondered, begun to yearn for a daughter?

“Why wasn’t mother interested?” I asked.

“I don’t remember,” he said. Subject closed.

On another of our drives in that last year, he asked me if I had anything in the works in the way of business. I told him I had been invited to give a lecture in Philadelphia. He inquired if there was a fee. I said there was: $5,000.

“For an hour’s talk?” he said, a look of astonishment on his face.

“Fifty minutes, actually,” I said, unable to resist provoking him lightly. His look changed from astonishment to bitter certainty. The country had to be in one hell of a sorry condition if they were passing out that kind of dough for mere talk from his son.

Was he, then, a good father? This was the question an acquaintance put to me at lunch recently. When I asked what he meant by good, he said: “Was he, for example, fair?”

My father was completely fair, never showing the least favoritism between my brother and me (a judgment my brother has confirmed). He also set an example of decency, nicely qualified by realism. “No one is asking you to be an angel in this world,” he told me when I was fourteen, “but that doesn’t give you warrant to be a son-of-a-bitch.” And, as this suggests, he was an unrelenting fount of advice, some of it pretty obvious, none of it stupid. “Always put something by for a rainy day.” “People know more about you than you think.” “Work for a man for a dollar an hour—always give him a dollar and a quarter’s effort.”

Some of his advice seemed wildly misplaced. “Next to your brother, money’s your best friend,” was a remark made all the more unconvincing by the fact that my brother and I, nearly six years apart in age, were never that close to begin with. On the subject of sex, the full extent of his wisdom was: “Be careful.” Of what, exactly, I was to be careful—venereal disease? pregnancy? getting entangled with the wrong girl?—he never filled in.

My father and I spent a lot of time together when I was an adolescent. He manufactured and imported costume jewelry (also known as junk jewelry) and novelties—identification bracelets, cigarette lighters, miniature cameras, bolo ties—which he sold to Woolworth’s, to the International Shoe Company, to banks, and to concessionaires at state fairs. I traveled with him in the summer, spelling him at the wheel of his Buicks and Oldsmobiles, toting his sample cases, writing up orders, listening to him tell— ad infinitum, ad nauseam —the same three or four jokes to customers. We shared rooms in less than first-class hotels in Midwestern towns— Des Moines, Minneapolis, Columbus—but never achieved anything close to intimacy, at least in our conversation. His commercial advice was as useful as his advice about sex. “Always keep a low overhead.” “You make your money in buying right, you know, not in selling.” “Never run away from business.” Some of it has stuck, however: nearly a half-century later, I still find it hard to turn down a writing assignment lest I prove guilty of running away from business.

My least favorite of his maxims was: “You can’t argue with success.” In my growing-up days, I thought there was nothing better to argue with. I tried to tell him why, but I never seemed to get my point across. The only time our arguments ever got close to the shouting stage was over the question of whether or not federal budgets had to be balanced. I was then in my twenties, and our ignorance on this question was equal and mutual—though he turned out to be right: all things considered, balanced is better.

WHEN NOT in his homiletic mode, my father could be very penetrating. “There are three ways to do business in this country,” he once told me. “At the top level you rely heavily on national advertising and public relations. At the next level, you take people out to dinner or golfing, you buy them theater tickets, supply women. And then there’s my level.” Pause. Asked what went on there, he replied: “I cut prices.” His level, I thought then and still think, was much the most honorable.

He appreciated jokes, although in telling them he could not sustain even a brief narrative. His own best wit entailed a comic resignation. In his late eighties, he made the mistake of sending to a great-nephew whom he had never met a bar-mitzvah check for $1,000, instead of the $100 he had intended. When I discovered the error and pointed it out to him, he paused only briefly, smiled, and said, “Boy, is his younger brother going to be disappointed.”

Work was the place where my father seemed most alive, most impressive. Born in Montreal and having never finished high school, he came to America at seventeen, not long before the Depression. He took various flunky jobs, but soon found his niche as a salesman. “Kid,” one of his bosses once told him, so good was he at his work, “try to remember that this desk I’m sitting behind is not for sale.” Eventually, he owned his own small business.

He worked six days a week, usually arriving at 7:30 a.m. If he could find some excuse to go down to work on Sunday, he was delighted to do so. On his rare vacations, he would call in two or three times a day to find out what was in the mail, who telephoned, what deliveries arrived.

He never had more than seven or eight employees, but the business was fairly lucrative. In the late 1960’s I recall him saying to me, “The country must be in terrible shape. You should see the crap I’m selling.” In later years, a nephew worked for him; neither my brother nor I ever seriously thought about joining the business, sensing early on that it was a one-man show, without sufficient oxygen for two. One day, after he had had a falling-out with this nephew, my father said to me, “He’s worked for me for fifteen years. We open at 8: 30, and for fifteen years he has come in at exactly 8:30. You’d think once—just once—the kid would be early.”

“I call people rich,” Henry James has Ralph Touchett say in The Portrait of a Lady, “when they’re able to meet the requirements of their imagination.” Although not greatly wealthy, my father made enough money fully to meet the demands of his. He could give ample sums to (mostly Jewish) charities, help out poor relatives, pay for his sons’ education, buy his wife the diamonds and furs and good clothes that were among the trophies of my parents’ generation’s success, in retirement take his grandsons to Israel, Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Soviet Union, New Zealand. At the very end, he told me that what most pleased him about his financial independence was never having to fall back on anyone else for help, right up to and including his exit from the world.

IN MY late twenties, my father, then in his late fifties, had a mild heart attack, and I feared I would lose him without ever getting to know him better. Having just recently returned to Chicago after a stint directing the anti-poverty program in Little Rock, Arkansas, I thought it might be a good thing if we were to meet once a week for lunch. On the first of these occasions, I took him to a French restaurant on the near north side. The lunch lasted nearly 90 minutes. I could practically smell his boredom, feel his longing to get back to “the place,” as he called his business, then located on North Avenue west of Damon. We never lunched alone again until after my mother’s death, when I felt he needed company.

At some point—around, I think, the time he hit sixty—my father, like many another successful man operating within a fairly small circle, ceased listening. A courteous, even courtly man, he was, please understand, never rude. He would give you your turn and not interrupt, nodding his head in agreement at much of what you said. But he was merely waiting—waiting to insert one of his own thoughts. He had long since mastered the falsely modest introductory clause, which he put to regular use: “I’m inclined to believe that there is more good than bad in the world,” he might offer, or “I may be mistaken, but don’t you agree that disease and war are Mother Nature’s way of thinning out the population?” I winced when I learned that the father of a friend of mine, having met him a few times, had taken to referring to my father as “the Rabbi.”

Although he did not dwell on the past, neither was he much interested in the future. He had an astonishing ability to block things out, including his own illnesses, even surgeries. He claimed to have no memory of his heart attack, and he chose not to remember that, like many men past their mid-eighties, he had had prostate cancer. “I’m a great believer in mind over matter,” he used to say.

He also liked to say that there wasn’t anything really new under the sun. When I would report some excess to him—for example, a lunch check of $180 for two in New York—he would say: “What’re ya, kidding me?” Although he was greatly interested in human nature, psychology at the level of the individual held no attraction for him. If I told him about someone’s odd or unpredictable or stupid behavior, he would respond, “What is he, crazy?”

Then, after his retirement at seventy-five, my father began to write. His own father had composed two books—one in Hebrew and one in Yiddish—for which my father had paid most of the expense of private publication. Offering to sell some of these books, he kept a hundred or so copies stored in our basement. This turned out to be a ruse for increasing the monthly stipend he was already sending my grandfather: each month he would add $30, $45, or $50, saying it represented payment for books he had sold. Then one day a UPS truck pulled up with another hundred books and a note from my grandfather, who had grown worried that his son’s stock was running low.

And now here was I, his eldest son, also publishing books. My father must have felt—with a heavy dose here of mutatis mutandis—like the Mendelssohn who was the son of the philosopher and the father of the composer but never quite had his own shot at a touch of intellectual glory. So he, too, began writing. His preferred form was the two- or three-sentence pensée (he would never have called it that), usually pointing a moral. “Man forces nature to reveal her chemical secrets,” is an example of his work in this line. “Nature evens the score because man cannot always control the chemicals.”

In the middle of the morning my phone would ring, and it would be my father with a question: “How do you spell affinity?” Then he would ask if he was using the word correctly in the passage he was writing, which he would read to me. I always told him I thought his observations were interesting, or accurate, or that I had never thought of the point he was making. Often I tossed in minor corrections, or I might suggest that his second sentence didn’t quite follow from his first. I loved him too much to say that a lot of what he had written bordered on the commonplace and, alas, often crossed that border. I’m not sure he cared all that much about my opinion anyway.

He began to carry a small notepad in his shirt pocket. On his afternoon walks, new material would occur to him. Adding pages daily—hourly, almost—he announced one day that he had a manuscript of more than a thousand pages. He referred to these writings offhandedly as “my stuff,” or “my crap,” or “the chazerai I write.” Still, he wanted to know what I thought about sending them to a publisher. The situation was quite hopeless; but I lied, said it was worth a try, and wrote a letter over his name to accompany a packet of fifty or so pages of typescript. He began with the major publishers, then went to the larger university presses, then to more obscure places.

After twenty or so rejections, I suggested a vanity-press arrangement—never using the deadly word “vanity.” For $10,000 or so, he could have 500 copies of a moderate-size book printed for his posterity. But he had too much pride for that, and after a while he ceased to send out his material. What he was writing, he concluded, had too high a truth quotient—it was, he once put it to me, “too hot”—for the contemporary world. But he kept on scribbling away, flagging only in the last few years of his life, when he complained that his inspiration was drying up.

Altogether, he had ended up with some 2,700 pages—his earnest, ardent attempt to make sense of the world before departing it. Although he had no more luck in this than the rest of us, there was, indisputably, something gallant about the attempt.

BECOMING AWARE of our fathers’ fallibilities is a jolt. When I was six years old, we lived in a neighborhood where I was the youngest kid on the block and thus prey to eight- and nine-year-olds with normal boyish bullying tendencies. One of them, a kid named Denny Price, was roughing me up one day when I told him that if he didn’t stop, my father would get him. “Ya fadda,” said Denny Price, “is an asshole.” Even to hear my father spoken of this way sickened me. I would have preferred another punch in the stomach.

World War II was over by the time I was eight, but I remember being disappointed that my father had not gone to fight. (He was too old.) I also recall my embarrassment—I was nine—at seeing him at an office party of a jewelry company he then worked for (Beiler-Levine on Wabash Avenue), clownishly placing his hand on the stomach of a pregnant secretary, closing his eyes, and predicting the sex of the child.

He was less stylish than many of my friends’ fathers. He had no clothes for leisure, and when he went to the beach (which he rarely did), he marched down in black business shoes, socks with clocks on them, and very white legs. He cared not at all about sports—which, when young, was the only thing I did care about. Later, I saw him come to wrong decisions about real estate, worry in a fidgeting way over small sums he was owed, make serious misjudgments about people. He preferred to operate, rather as in his writing, at too high a level of generality. “Mother nature abhors a vacuum,” he used to say, and I, to myself, would think, “No, Dad, it’s a vacuum-cleaner salesman she abhors.” At some point in my thirties I concluded that my father was not nearly so subtle or penetrating as my mother.

What do boys and young men want from their fathers? For the most part I think we want precisely what they cannot give us—a painless transfusion of wisdom, a key to life’s mysteries, the secret to happiness, assurance that one’s daily struggles and aggravations amount to something more than some stupid cosmic joke with no punch line. Oh, Dad, you have been here longer than I, you have been in the trenches, up and over the hill, quick, before you exit, fill me in: does it all add up, cohere, make any sense at all, what’s the true story, the real emes, tell me, please, Dad? By the time my father reached sixty, I knew he could not deliver any of this.

But, now past sixty myself, I cannot say I expect to do better. Besides, the virtues my father did have, and did deliver on, were impressive. Steadfastness was high on the list. He was a man you could count on. He saw my mother through a three-year losing fight against cancer, doing the shopping, the laundry, even some of the cooking, trying to keep up her spirits, never letting his own spirits fall. He called himself a realist, but he was in fact a sentimentalist, with a special weakness, in his later years, for his extended family. (He and his twin brother were the youngest of ten children, eight boys and two girls, my father being the only financial success among them.) He had great reverence for his own father, always repeating his sayings, marveling at his wisdom.

We may not have reverenced him; but certainly we paid him obeisance. His was the last generation of fathers to draw off the old Roman authority of the paterfamilias. The least tyrannical of men, my father was nevertheless accorded a high level of service at home because of his role as head of the household and efficient breadwinner. Dinner always awaited his return from work. One did not open the evening paper until he had gone through it first. “Get your father a glass of water,” my mother would say, or, “Get your father his slippers,” and my brother and I would do so without quibble. A grandfather now myself, I have never received, nor ever expect to receive, any of these little services.

My father lived comfortably with his contradictions—another great virtue, I think. He called himself an agnostic, for example, and belonged to no synagogue, yet it was clear that he would have been greatly disappointed had any of his grandsons not had a bar mitzvah. He always invoked the soundness of business principles, yet in cases of the least conflict between these principles and a generous impulse, he would inevitably act on the latter: loaning money to the wrong people, giving breaks to men who did not seem to deserve them, helping out financially whenever called upon to do so. To bums stopping him for a handout he used to say, “Beat it. I’m working this side of the street,” yet he gave his old suits and overcoats to a poor brain-fozzled alcoholic who slept in the doorways on North Avenue near his place of business.

NOT LONG before my high-school graduation, my father told me that he would naturally pay for college but wondered if maybe I, who had never shown even mild interest as a student, might not do better to forget about it. “I think you have the makings of a terrific salesman,” he said. But he let me make the decision. I chose college, chiefly because most of my friends were going and I, still stalling for time, was not yet ready to go out into the world.

But then my father allowed me to make nearly all my own decisions. True, he had insisted that I go to Hebrew school, on the grounds, often repeated, that “A Jew should know something of his background, about where he comes from.” But apart from that, my brother and I decided what we would study, where we would go to school, and with whom. He never told me what kind of work to go into, offering only another of his much-repeated apothegms: “You’ve got to love your work.” He never told me whom or what kind of woman to marry, how to raise children, what to do with my money. He let me go absolutely my own way.

Only now does it occur to me that I never sought my father’s approval; growing up, I mainly tried to avoid his disapproval, so that I could retain the large domain of freedom he permitted me. For starters, he was unqualified to dispense approval where I sought it: for my athletic prowess when young; for my intellectual work when older. Then, too, artificially building up his sons’ confidence through a steady stream of heavy and continuous approval—the modus operandi of many contemporary parents—was not his style. “You handled that in a very business-like way,” my father once told me about some small matter I had arranged for him, but I cannot recall his otherwise praising me. I would send him published copies of things I wrote, and he would read them, usually confining his response to “very interesting” or remarking on how something I said had suggested a thought of his own.

In my middle thirties I was offered a job teaching at a nearby university. In balancing the debits and credits of the offer, I suggested to my father that the job would allow me to spend more time with my two sons. “I don’t mean to butt in,” he said, before proceeding to deliver the longest speech of his paternal career, “but that sounds to me like a load of crap. If you’re going to take a teaching job, take it because you want to teach, or because you can use the extra time for other work, not because of your kids. Con yourself into thinking you make decisions because of your children and you’ll end up one of those pathetic old guys whining about his children’s ingratitude. Your responsibilities to your sons include feeding them and seeing they have a decent place to live and helping them get the best schooling they’re capable of and teaching them right from wrong and making it clear they can come to you if they’re in trouble and setting them an example of how a man should live. That’s how I looked upon my responsibility to you and your brother. But for a man, work comes first.”

In the raising of my own sons, I attempted, roughly, to imitate my father—but already the historical moment for confidence of the kind he had brought to fatherhood was past. For one thing, I was a divorced father (though with custody of my sons), so I had already done something to them that my father never did to me—break up their family. For another, I found myself regularly telling my sons that I loved them. I told them this so often that they probably came to doubt it.

True, I wasn’t like one of those fathers who these days show up for all their children’s school activities, driving them to four or five different kinds of lessons, making a complete videotaped record of their first eighteen years, taking them to lots of ball games, art galleries, and (ultimately, no doubt) the therapist. But I was, nonetheless, plenty nervous in the service, wondering if I was doing the right thing, never really confident I was good enough—or even adequate. The generation of fathers now raising children, I sense, is even more nervous than I was then, and the service itself, thanks to feminism and other factors, has become a good deal more arduous.

MANY ARE the kinds of bad luck one can have in a father. Being the son of certain men—I think here of Alger Hiss’s son, Tony, who seems to have devoted so much of his life to defending his father’s reputation—can seem almost a full-time job. One can have a father whose success is so great as to stunt one’s own ambition, or a father whose failure has so embittered him as to leave one with permanently bleak views and an overwhelmingly dark imagination of disaster. Having too strong a father can be a problem, but so can having too weak a father. A father may desert his family and always leave one in doubt, or a father may commit suicide and leave one in a despair much darker and deeper than any doubt. Worst luck of all, perhaps, is to have one’s father die of illness or accident before one has even known him.

“They fuck you up, your mum and dad,” famously wrote Philip Larkin, in a line that is not only amusing but, it is agreed, universally true. But need it be true? Ought one to blame one’s parents for all that one (disappointingly) is, or that one (equally disappointingly) has never become? One of the most successful men I know once told me, without the least passion in his voice, “Actually, I dislike my parents quite a bit”—which didn’t stop him, when his parents were alive, from being a good and dutiful son. (We are, after all, commanded to honor our parents, not necessarily to love them.) Taking the heat off parents for the full responsibility for the fate of their children throws the responsibility back on oneself, where it usually belongs. “I mean, I blame for every fuckups in my life my parents?,” asked Mikhail Baryshnikov, who had a horrendously rough upbringing. His resounding answer to his own question was “No.”

The best luck is, of course, to love one’s parents without complication, which has been my fortunate lot. Whether consciously or not—I cannot be certain even now—my parents gave me the greatest gift of all. By leaving me alone, while somehow never leaving me in doubt that I could count upon them when needed, they gave me the freedom to go my own way and to become myself. Of the almost cripplingly excessive concern for the proper rearing of children in our own day, in all its fussiness and fear, my father’s response, I’m almost certain, would have been: “What’re they, crazy?”

JOSEPH EPSTEIN is the author of sixteen books. The most recent are Fabulous Small Jews (Houghton Mifflin), a collection of stories many of which first appeared in COMMENTARY, and Envy (Oxford), a volume in a series on the seven deadly sins. Epstein was honored by President George W. Bush with a 2003 National Humanities Medal.

Copyright © 2003 Commentary Magazine

Eat Your Heart Out, David Letterman!

Forget Late Night With David Letterman! Sapper's (Fair & Balanced) Rants & Raves provides the Top Ten Myths About Thanksgiving without fanfare. If this be (fair & balanced) mockery, so be it!

[x History News Network]

Top 10 Myths About Thanksgiving

By Rick Shenkman

MYTH # 1

The Pilgrims Held the First Thanksgiving

To see what the first Thanksgiving was like you have to go to: Texas. Texans claim the first Thanksgiving in America actually took place in little San Elizario, a community near El Paso, in 1598 -- twenty-three years before the Pilgrims' festival. For several years they have staged a reenactment of the event that culminated in the Thanksgiving celebration: the arrival of Spanish explorer Juan de Onate on the banks of the Rio Grande. De Onate is said to have held a big Thanksgiving festival after leading hundreds of settlers on a grueling 350-mile long trek across the Mexican desert.

Then again, you may want to go to Virginia.. At the Berkeley Plantation on the James River they claim the first Thanksgiving in America was held there on December 4th, 1619....two years before the Pilgrims' festival....and every year since 1958 they have reenacted the event. In their view it's not the Mayflower we should remember, it's the Margaret, the little ship which brought 38 English settlers to the plantation in 1619. The story is that the settlers had been ordered by the London company that sponsored them to commemorate the ship's arrival with an annual day of Thanksgiving. Hardly anybody outside Virginia has ever heard of this Thanksgiving, but in 1963 President Kennedy officially recognized the plantation's claim.

MYTH # 2

Thanksgiving Was About Family

If by Thanksgiving, you have in mind the Pilgrim festival, forget about it being a family holiday. Put away your Norman Rockwell paintings. Turn off Bing Crosby. Thanksgiving was a multicultural community event. If it had been about family, the Pilgrims never would have invited the Indians to join them.

MYTH # 3

Thanksgiving Was About Religion

No it wasn't. Paraphrasing the answer provided above, if Thanksgiving had been about religion, the Pilgrims never would have invited the Indians to join them. Besides, the Pilgrims would never have tolerated festivities at a true religious event. Indeed, what we think of as Thanksgiving was really a harvest festival. Actual "Thanksgivings" were religious affairs; everybody spent the day praying. Incidentally, these Pilgrim Thanksgivings occurred at different times of the year, not just in November.

MYTH # 4

The Pilgrims Ate Turkey

What did the Pilgrims eat at their Thanksgiving festival? They didn't have corn on the cob, apples, pears, potatoes or even cranberries. No one knows if they had turkey, although they were used to eating turkey. The only food we know they had for sure was deer. 11(And they didn't eat with a fork; they didn't have forks back then.)

So how did we get the idea that you have turkey and cranberry and such on Thanksgiving? It was because the Victorians prepared Thanksgiving that way. And they're the ones who made Thanksgiving a national holiday, beginning in 1863, when Abe Lincoln issued his presidential Thanksgiving proclamations...two of them: one to celebrate Thanksgiving in August, a second one in November. Before Lincoln Americans outside New England did not usually celebrate the holiday. (The Pilgrims, incidentally, didn't become part of the holiday until late in the nineteenth century. Until then, Thanksgiving was simply a day of thanks, not a day to remember the Pilgrims.)

MYTH # 5

The Pilgrims Landed on Plymouth Rock

According to historian George Willison, who devoted his life to the subject, the story about the rock is all malarkey, a public relations stunt pulled off by townsfolk to attract attention. What Willison found out is that the Plymouth Rock legend rests entirely on the dubious testimony of Thomas Faunce, a ninety-five year old man, who told the story more than a century after the Mayflower landed. Unfortunately, not too many people ever heard how we came by the story of Plymouth Rock. Willison's book came out at the end of World War II and Americans had more on their minds than Pilgrims then. So we've all just gone merrily along repeating the same old story as if it's true when it's not. And anyway, the Pilgrims didn't land in Plymouth first. They first made landfall at Provincetown. Of course, the people of Plymouth stick by hoary tradition. Tour guides insist that Plymouth Rock is THE rock.

MYTH # 6

Pilgrims Lived in Log Cabins

No Pilgrim ever lived in a log cabin. The log cabin did not appear in America until late in the seventeenth century, when it was introduced by Germans and Swedes. The very term "log cabin" cannot be found in print until the 1770s. Log cabins were virtually unknown in England at the time the Pilgrims arrived in America. So what kind of dwellings did the Pilgrims inhabit? As you can see if you visit Plimoth Plantation in Massachusetts, the Pilgrims lived in wood clapboard houses made from sawed lumber.

MYTH # 7

Pilgrims Dressed in Black

Not only did they not dress in black, they did not wear those funny buckles, weird shoes, or black steeple hats. So how did we get the idea of the buckles? Plimoth Plantation historian James W. Baker explains that in the nineteenth century, when the popular image of the Pilgrims was formed, buckles served as a kind of emblem of quaintness. That's the reason illustrators gave Santa buckles. Even the blunderbuss, with which Pilgrims are identified, was a symbol of quaintness. The blunderbuss was mainly used to control crowds. It wasn't a hunting rifle. But it looks out of date and fits the Pilgrim stereotype.

MYTH # 8

Pilgrims, Puritans -- Same Thing

Though even presidents get this wrong -- Ronald Reagan once referred to Puritan John Winthrop as a Pilgrim -- Pilgrims and Puritans were two different groups. The Pilgrims came over on the Mayflower and lived in Plymouth. The Puritans, arriving a decade later, settled in Boston. The Pilgrims welcomed heterogeneousness. Some (so-called "strangers") came to America in search of riches, others (so-called "saints") came for religious reasons. The Puritans, in contrast, came over to America strictly in search of religious freedom. Or, to be technically correct, they came over in order to be able to practice their religion freely. They did not welcome dissent. That we confuse Pilgrims and Puritans would have horrified both. Puritans considered the Pilgrims incurable utopians. While both shared the belief that the Church of England had become corrupt, only the Pilgrims believed it was beyond redemption. They therefore chose the path of Separatism. Puritans held out the hope the church would reform.

MYTH # 9

Puritans Hated Sex

Actually, they welcomed sex as a God-given responsibility. When one member of the First Church of Boston refused to have conjugal relations with his wife two years running, he was expelled. Cotton Mather, the celebrated Puritan minister, condemned a married couple who had abstained from sex in order to achieve a higher spirituality. They were the victims, he wrote, of a "blind zeal."

MYTH # 10

Puritans Hated Fun

H.L. Mencken defined Puritanism as "the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy!" Actually, the Puritans welcomed laughter and dressed in bright colors (or, to be precise, the middle and upper classes dressed in bright colors; members of the lower classes were not permitted to indulge themselves -- they dressed in dark clothes). As Carl Degler long ago observed, "The Sabbatarian, antiliquor, and antisex attitudes usually attributed to the Puritans are a nineteenth-century addition to the much more moderate and wholesome view of life's evils held by the early settlers of New England."

Rick Shenkman is the editor of HNN.

Copyright © 2003 HNN

Should Presidents Read Newspapers?

This is unbelievable! Ronald Reagan was an avid reader of newspapers! W—the self-annointed second coming of the Great Communicator—reads no newspapers because they don't project an optimistic picture of him! Duh! If this be (fair & balanced) ignorance, so be it!

[x History News Network]

Should Presidents Read Newspapers?

"It's not to say I don't respect the press. I do respect the press. But sometimes it's hard to be an optimistic leader. A leader must project an optimistic view. It's hard to be optimistic if you read a bunch of stuff about yourself." -- President Bush, in an interview with British journalist Martin Newland, Nov. 14, 2003

In a recent interview President Bush revealed that he doesn't read newspapers. Though he occasionally glances at the headlines, he relies on his advisors to provide him with "objective" accounts, "And the most objective sources I have are people on my staff who tell me what's happening in the world." He said this has been his practice since he became president.

President Bush's reliance on aides for news is at variance with the previous occupants of his office. President Eisenhower, according to his press secretary, read nine newspapers a day. President Kennedy also read multiple newspapers; to digest the news quickly he famously signed up for Evelyn Wood's speed reading course--and insisted that other high officials do as well. Lyndon Johnson was by his own confession a news junkie.

Richard Nixon began his day by reading a special news digest, upwards of sixty pages, prepared by aides (including Patrick Buchanan) that reported on the contents of dozens of papers across the country. Although the digest was often packed to suit Nixon's biases (aides included articles that played to his prejudices against liberals), the news summary offered an extraordinarily broad exposure to events and views. Nixon would jot his reactions to stories in the margins, indicating the action he wanted officials to take in response to developments. Biographer Stephen Ambrose observed that Nixon in effect governed the country through these jottings.

Ronald Reagan was an avid reader of newspapers. His ex-wife Jane Wyman confessed to friends that she was bored by his constant diatribes about news. Both Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clifton read the papers daily.

Copyright © 2003 HNN

Tuesday, November 25, 2003

American Amnesia Is Fatal

The chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities descries rampant historical ignorance in the United States. Of course, Amarillo College—my academic home for the past 32 years—has insisted on lumping history into a department called Social Sciences to differentiate it from the K-12 misnomer of Social Studies. History is one of the humanities. One of the nine Muses of Greek mythology was Clio, goddess of history. The ancient Greeks knew nothing of the Social Sciences, much less the Social Studies. Clio was not a Social Scientist nor a Social Student. Names and words are powerful. No wonder most of my students at Amarillo College have thought they were in Grade 13; Amarillo College doesn't use college language. There is enough ignorance to go around and then some. If this be (fair & balanced) elitism, so be it.

How to Combat 'American Amnesia'

The humanities are vital to our country's defense.

BY BRUCE COLE

In his Inaugural Address, President Bush called on all Americans to be citizens, not spectators; to serve our nation, beginning with our neighbors; to speak for the values that gave our nation birth. That call took on new meaning after the attacks of September 11. We witnessed the true measure of what it is to be a good citizen--when evil is countered with acts of courage and compassion.

As chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, my duty is to share the wisdom of the humanities with all Americans. The humanities are, in short, the study of what makes us human: the legacy of our past, the ideas and principles that motivate us, and the eternal questions that we still ponder. The classics and archeology show us whence our civilization came. The study of literature and art shape our sense of beauty. The knowledge of philosophy and religion give meaning to our concepts of justice and goodness.

The NEH was founded in the belief that cultivating the best of the humanities has real, tangible benefits for civic life. Our founding legislation declares that "democracy demands wisdom." America must have educated and thoughtful citizens who can fully and intelligently participate in our government of, by and for the people. The NEH exists to foster the wisdom and knowledge essential to our national identity and survival.

Indeed, the state of the humanities has real implications for the state of our union. Our nation is in a conflict driven by religion, philosophy, political ideology and views of history--all humanities subjects. Our tolerance, our principles, our wealth and our liberties have made us targets. To understand this conflict, we need the humanities.

The values implicit in the study of the humanities are part of why we were attacked. The free and fearless exchange of ideas, respect for individual conscience, belief in the power of education--all these things are anathema to our country's enemies. Understanding and affirming these principles is part of the battle.

The attack on September 11 targeted not only innocent civilians, but also the very fabric of our culture. The terrorists struck the Twin Towers and the Pentagon and aimed at either the White House or Capitol dome--all structures rich in meaning and bearing witness to the United States' free commerce, military strength and democratic government. As such, they also housed many of the artifacts--the manuscripts, art and archives--that form our history and heritage.

In the weeks following the attack, the NEH awarded a grant to an organization that conducted a survey of the damage to our cultural holdings. They found that the attack obliterated numerous art collections of great worth. Cantor Fitzgerald's renowned "museum in the sky" is lost, as well as priceless works by Rodin, Picasso, Hockney, Lichtenstein, Corbusier, Miro and others.

Archaeological artifacts from the African Burial Ground and other Manhattan sites are gone forever, as are irreplaceable records from the Helen Keller archives. Artists perished alongside their artifacts. Sculptor Michael Richards died as he worked in his studio on the 92nd floor of Tower One. His last work, now lost, was a statue commemorating the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II.

Of course, the loss of artifacts and art, no matter how priceless and precious, is dwarfed by the loss of life. Yet preserving and protecting our cultural holdings is of immense importance to civic life. Our cultural artifacts carry important messages about who we are and what we are defending. These irreplaceable objects are among our enemies' targets.

The Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn and Bay Bridges, our skyscrapers, the Liberty Bell, our libraries and our schools are all potential targets--precisely because they stand as symbols of America's defining principles.

In light of that fact, today it is all the more urgent that we study American institutions, culture and history. Defending our democracy demands more than successful military campaigns. It also requires an understanding of the ideals, ideas and institutions that have shaped our country.

This is not a new concept. America's founders recognized the importance of an informed and educated citizenry as necessary for the survival of our participatory democracy. James Madison famously said, "The diffusion of knowledge is the only true guardian of liberty." Such knowledge tells us who we are as a people and why our country is worth fighting for. Such knowledge is part of our homeland defense.

Our values, ideas and collective memories are not self-sustaining. Just as free peoples must take responsibility for their own defense, they also must pass on to future generations the knowledge that sustains democracy.

It has been said that the erosion of freedom comes from three sources: from without, from within and from the passing of time. Though not as visible as marching armies, the injuries of time lead to the same outcome: a surrender of American ideals. Abraham Lincoln warned of this "silent artillery"--the fading memory of what we believe as Americans and why. And this loss of American memory has profound implications on our national security.

All great principles and institutions face challenges, and the wisdom of the humanities, and the pillars of democratic self-government, are not immune. We face a serious challenge to our country that lies within our borders--and even within our schools: the threat of American amnesia.

One of the common threads of great civilizations is the cultivation of memory. Many of the great works of antiquity are transliterated from oral traditions. From Homer to "Beowulf," such tales trained people to remember their heritage and history through story and song, and pass those stories and songs throughout generations. Old Testament stories repeatedly depict prophets and priests encouraging people to remember, to "write on their hearts" the events, circumstances and stories that make up their history.

We are in danger of forgetting this lesson. For years, even decades, polls, tests and studies have shown that Americans do not know their history and cannot remember even the most significant events of the 20th century.

Of course, Americans are a forward-looking people. We are more concerned with what happens tomorrow than what happened yesterday. But we are in peril of having our view of the future obscured by our ignorance of the past. We cannot see clearly ahead if we are blind to history. Unfortunately, most indicators point to a worsening of our case of American amnesia.

I'll give just a few examples. One study of university students found that 40% could not place the Civil War in the correct half-century. Only 37% knew that the Battle of the Bulge took place during World War II. A national test of high school seniors found that 57% performed "below basic" level in American history. What does that mean? Well, over half of those tested couldn't say whom we fought in World War II. Eighteen percent believed that the Germans were our allies!

Such collective amnesia is dangerous. Citizens kept ignorant of their history are robbed of the riches of their heritage, and handicapped in their ability to understand and appreciate other cultures.

If Americans cannot recall whom we fought, and whom we fought alongside, during World War II, it should not be assumed that they will long remember what happened on September 11 or why we must be prepared and vigilant today. And a nation that does not know why it exists, or what it stands for, cannot be expected to long endure. As columnist George Will wrote, "We cannot defend what we cannot define."

Our nation's future depends on how we meet these challenges. We all have a stake, and a role to play, in recovering America's memory. There are several things we can do to alleviate our serious case of American amnesia.

This is where the National Endowment for the Humanities is answering the President's call to service. Announced by President Bush last September, the We the People initiative marks a systematic effort at the NEH to promote the study and understanding of American history and culture.

The President has requested $100 million over the next three years to support the initiative. If you watched and enjoyed Ken Burns's "The Civil War," you have seen the kind of public program we are supporting. We are working on equally powerfully projects for museums, scholars, teachers and students. Young people will compete for $10,000 in prizes in the annual "Idea of America" essay contest. Other nationwide programs will reach students from kindergarten through college.

In the coming months and years, I want the NEH to help lead a renaissance in knowledge about our history and culture. We are the inheritors and guardians of a noble tradition, citizens of a democracy taking personal responsibility for our common defense. It is a heritage that extends back to the first democracies of Ancient Greece and runs through the whole history of our country.

Our values and traditions must be preserved and passed on. Without an active and informed citizenry, neither the toughest laws nor the strongest military can preserve our freedom. Knowing our nation's past, our founding ideas and our legacy of liberty is crucial to our homeland defense.

Our nation has faced many difficult challenges in the past, but, just as history teaches us to remain vigilant, it also shows us--with such vigilance--liberty and justice will prevail.

Bruce Cole is chairman of the National Endowment of the Humanities. This is adapted from a speech he gave at the National Citizen Corps Conference on July 29.

Copyright © 2003 The Wall Street Journal

Just In Time! The Rules Of Thanksgiving

Another bit of Thanksgiving wisdom, courtesy of Sapper's (Fair & Balanced) Rants & Raves. If this be (fair & balanced) generosity of spirit, so be it.

[x New Yorker]

THANKSGIVING RULES REVISED

by BRUCE McCALL

The Three Wise Men of Thanksgiving (Three men offering their holiday advice, 1You don’t really want to deep-fry an entire turkey on a hot plate in a bitsy apartment. 2Nobody is forcing you to play touch football. 3There is no need to drink a lot of cranberry liqueur.’)

Copyright © 2003 The New Yorker

Post this document within ten feet of all liquor cabinets, TV sets, sofas, and any distant relations who are still sitting or standing upright.

Article XII of the 1663 Jamestown Convention has been amended as of this date to include the following:

1. Thanksgiving-dinner guests are no longer required to play Scrabble, Go Fish, or Monopoly with children under the age of ten. Withholding of liquor is coercion.

2. A shaker of Martinis no longer has official standing as Thanksgiving breakfast. Early risers: the Thanksgiving Day cocktail hour now begins only after you have arrived at the venue and parked your car, and never before sunrise.

3. You cannot decline the Kansas Riesling served with dinner out of professed adherence to the claim that “the official Thanksgiving mascot is the 101-proof Wild Turkey.” This is apocryphal.

4. The mandatory minimum number of guests related by blood to the host/hostess is increased to sixteen. Seating them on the sun porch, in the attic, or in the basement for the Thanksgiving meal is no longer permissible, nor is the requirement that they wear bags over their heads and/or name tags. Asking how they’re doing remains optional.

5. In-laws must now be accorded full human status. Their chairs must face the dinner table, and they must be offered a choice of dark or white meat.

6. Native American guests must now be offered bourbon, Scotch, gin, or other alcoholic beverages by name. They must not be described as “heap strong firewater.”

7. When you are handed a family scrapbook or photo album, you must keep such article in your possession for at least a hundred and twenty seconds before passing it to the next person. You may not ask if your hundred and twenty seconds are up.

8. Precocious children under twelve years of age may now be fitted with muzzles by a non-parent after the first hour.

9. Reminiscences that touch upon parental favoritism, unpaid personal loans, and arrests of blood relations’ children are discouraged.

10. You are entitled to ten naps per twelve-hour Thanksgiving Day period. Moments after 4 p.m., when time itself seems to have stopped, do not count as naps. Do not commence a nap when a blood relation older than you is addressing you directly.

11. You will be videotaped by your most moronic relation. Failing to coöperate by smiling / making funny faces / rushing the lens carries the penalty of spending next Thanksgiving at this relation’s home.

12. Vacating the premises before Thanksgiving dinner is served in order to “get a breath of fresh air,” “check the pressure in the tires,” or “watch for shooting stars” will now be considered a desertion of familial responsibilities, punishable by talking college football with an in-law for thirty minutes without the aid of an alcoholic beverage.

13. The host / hostess cannot depart the house, for any reason, until one hour after the last guest has left, been expelled, or vanished. (Check corners, crawl spaces, and under the dinner table before lights-out.)

Happy Thanksgiving! *

* “Happy Thanksgiving!” is meant only as an encouraging phrase and will not necessarily insure a result like the one depicted in the Norman Rockwell painting.

Copyright © 2003 The New Yorker

Happy Days Are Here Again

How high can the bubble float? Who'd of thought that Rants & Raves would be passing along investment tips? If this be a (fair & balanced) sure thing, so be it.

[x Business Wire]

Fitch Assigns Amarillo Jr College Dist, TX GOs Initial 'AA' Rtg

AUSTIN, Texas--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Nov. 25, 2003--Fitch Ratings assigns an initial 'AA' rating to $6.7 million of Amarillo Junior College District (AJC or the district), Texas' general obligation refunding bonds, series 2003, which are expected to price Dec. 1 via a syndicate led by Banc of America Securities LLC. Additionally, Fitch has assigned a 'AA' rating on the district's $12.6 million in outstanding general obligation bonds. The Rating Outlook is Stable.

Dated Dec. 15, 2003, the bonds mature serially beginning Feb. 15, 2004-2014 and are subject to optional redemption as prescribed in the offering statement. The bonds are direct and voted obligations of the district, payable from an ad valorem tax levy within the limits prescribed by law on all taxable property within the district. The maximum property tax rate for debt service is $0.50 per $100 taxable assessed valuation. Proceeds will be used to refund outstanding series 1994 bonds for interest savings.

Fitch's initial rating of 'AA' on the district's general obligation bonds reflects steady growth in its enrollment and tax base, low debt load, and satisfactory financial performance. While the combination of enrollment gains and reduced state appropriations present some financial challenge, comfort is provided by the availability of AJC's ample operating tax margin, low tuition rates, and competitive position in a large and modestly growing service area. The lack of a formal capital plan poses some risk. However, the district has historically taken a conservative approach to debt financing.

The district's taxing jurisdiction is coterminous with the City of Amarillo, which covers both Potter and Randall counties. The city's 2000 census grew by more than 10% since the last census and now totals over 179,000. Amarillo serves as the banking, distribution, and commercial center for the Texas panhandle. The district's entire service area, which includes 26 counties, is estimated to total about 400,000. Steady commercial and residential development, averaging over $200 million per year since fiscal 1999, has enabled the city to maintain steady and notably low unemployment rates. Health care and food production and distribution are the largest area employers.

Comprised of four campuses, the district's major capital programs were completed in the mid-1990's. The lack of additional debt financing since then has resulted in a very favorable debt profile and principal payout. Future debt plans are uncertain at this time given the recent appointment of the district's president. Deferred maintenance needs are reportedly modest and addressed through the ongoing use of current reserves.

Enrollment trends have been positive, with student headcount growing to more than 11,700 in fall 2003, a greater than 40% increase since fall 1998. A new branch campus has been proposed in Hereford by community residents; pending approval of a local maintenance tax, the district has agreed to begin operations in fall 2005.

Typically, public colleges and universities record break-even operating results. From fiscal 1998 to fiscal 2001, AJC has recorded essentially break-even or better operating margins. While a direct comparison with prior years' performance is difficult due to a change in reporting format, fiscal 2002 and preliminary fiscal 2003 results point to a continuation of prior year trends. Diversity of revenue sources lends to stability, with the district dependent on a combination of state appropriations, property taxes, and tuition and fees for operations.

As in the case of all state agencies, state appropriations have been reduced, beginning in fiscal 2003. However, reductions have been offset by expenditure cuts, tuition rate and property tax increases, as well as enrollment and tax base growth. No programs have been eliminated. In addition, liquidity remains favorable, with available funds to expenses covering over five months of operations.

Contacts

Fitch Ratings

Jose Acosta 512-322-5324, Austin

Mark Campa, 512-322-5316, Austin

Matt Burkhard, 212-908-0540, New York (Media Relations)

Give Me Molly Ivins Any Day Of The Week!

Ann Coulter—darling of the Radical Right—went over the top recently by expressing regret that Timothy McVeigh didn't blow up The New York Times instead of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. At her worst, Molly Ivins has never spewed such disgusting rhetoric. Coulter is the traitor. In fact, I think I like Timothy McVeigh better than Ann Coulter. Ann Coulter belongs in a porn site. Look at one of her own publicity stills. She probably looks hot in black vinyl to the Radical Righties who need visual stimulation for their self-abuse. If this is (fair & balanced) disgust, so be it!

A CT native, Coulter graduated with honors from Cornell and received her J.D. from University of Michigan Law School, where she was an editor of The Michigan Law Review.

The Uncivil War

By PAUL KRUGMAN

One of the problems with media coverage of this administration," wrote Eric Alterman in The Nation, "is that it requires bad manners."

He's right. There's no nice way to explain how the administration uses cooked numbers to sell its tax cuts, or how its arrogance and gullibility led to the current mess in Iraq.

So it was predictable that the administration and its allies, no longer very successful at claiming that questioning the president is unpatriotic, would use appeals to good manners as a way to silence critics. Not, mind you, that Emily Post has taken over the Republican Party: the same people who denounce liberal incivility continue to impugn the motives of their opponents.

Smart conservatives admit that their own side was a bit rude during the Clinton years. But now, they say, they've learned better, and it's those angry liberals who have a problem. The reality, however, is that they can only convince themselves that liberals have an anger problem by applying a double standard.

When Ann Coulter expresses regret that Timothy McVeigh didn't blow up The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal laughs it off as "tongue-in-cheek agitprop." But when Al Franken writes about lies and lying liars in a funny, but carefully researched book, he's degrading the discourse.

More important, the Bush administration — which likes to portray itself as the inheritor of Reagan-like optimism — actually has a Nixonian habit of demonizing its opponents.

For example, here's President Bush on critics of his economic policies: "Some say, well, maybe the recession should have been deeper. It bothers me when people say that." Because he used the word "some," he didn't literally lie — no doubt a careful search will find someone, somewhere, who says the recession should have been deeper. But he clearly intended to suggest that those who disagree with his policies don't care about helping the economy.

And that's nothing compared with the tactics now being used on foreign policy.

The campaign against "political hate speech" originates with the Republican National Committee. But last week the committee unveiled its first ad for the 2004 campaign, and it's as hateful as they come. "Some are now attacking the president for attacking the terrorists," it declares.

Again, there's that weasel word "some." No doubt someone doesn't believe that we should attack terrorists. But the serious criticism of the president, as the committee knows very well, is the reverse: that after an initial victory in Afghanistan he shifted his attention — and crucial resources — from fighting terrorism to other projects.

What the critics say is that this loss of focus seriously damaged the campaign against terrorism. Strategic assets in limited supply, like Special Forces soldiers and Predator drone aircraft, were shifted from Afghanistan to Iraq, while intelligence resources, including translators, were shifted from the pursuit of Al Qaeda to the coming invasion. This probably allowed Qaeda members, including Osama bin Laden, to get away, and definitely helped the Taliban stage its ominous comeback. And the Iraq war has, by all accounts, done wonders for Qaeda recruiting. Is saying all this attacking the president for attacking the terrorists?

The ad was clearly intended to insinuate once again — without saying anything falsifiable — that there was a link between Iraq and 9/11. (Now that the Iraq venture has turned sour, this claim is suddenly making the rounds again, even though no significant new evidence has surfaced.) But it was also designed to imply that critics are soft on terror.

All this fuss about civility, then, is an attempt to bully critics into unilaterally disarming — into being demure and respectful of the president, even while his campaign chairman declares that the 2004 election will be a choice "between victory in Iraq and insecurity in America."

And even aside from the double standard, how important is civility? I'm all for good manners, but this isn't a dinner party. The opposing sides in our national debate are far apart on fundamental issues, from fiscal and environmental policies to national security and civil liberties. It's the duty of pundits and politicians to make those differences clear, not to play them down for fear that someone will be offended.

Copyright © 2003 The New York Times Company

Monday, November 24, 2003

Gluttony & Thanksgiving

Is gluttony the deadliest sin? According to the Roman Catholic Church: pride is #1, envy #2, wrath #3, sloth #4, avarice #5, gluttony #6, and lust #7. Well, the annual gluttonous day is nigh. If this be (fair & balanced) guilt-mongering, so be it.

[x Boston Globe]

The deadliest sin

As Americans prepare to stuff themselves with turkey and pumpkin pie, two new books ask what's so bad about gluttony, anyway?

By Jim Holt

HERE ARE THREE propositions that sit together uneasily: 1) The United States is a deeply religious country. 2) Gluttony is one of the seven deadly sins. 3) Americans are the fattest people in the world.

The absolute fattest? Well, there may be a few South Sea islands where the people are heavier. But the United States, with 61 percent of its adults -- and one-quarter of its children -- overweight, certainly beats out everyone else. And that means there is a moral irony to be confronted, especially as we look forward to a national holiday later this week in which ritual overeating is deemed a gesture of gratitude for divine providence.

According to a 1998 Purdue University study, obesity is associated with higher levels of religious participation. (Broken down by creed, Southern Baptists have the highest body-mass index on average, Catholics are in the middle, and Jews and other non-Christians are the lowest.) When this finding was brought to the attention of the Reverend Jerry Falwell, he was unperturbed. "I know gluttony is a bad thing," Falwell said. "But I don't know many gluttons." That is one way out of the dilemma -- to deny that overweight people are necessarily sinful gluttons. But it could also be that gluttony is not really a sin.

What is so bad, in a moral sense, about eating extravagantly? As Sir Roy Strong stresses in his new book, Feast: A History of Grand Eating (Harcourt), the sybaritic pleasures to be gained from the copious consumption of food were regarded as perfectly honorable by the classical humanists. Nor is the idea that gastronomic indulgence is an outrage against the divine order to be found in the Bible. In Gluttony, the latest in a series of short books on the seven deadly sins published by the Oxford University Press, Francine Prose observes that most of the feasting in both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament "is, as it should be, celebratory, unclouded by guilt, regret or remorse."