What a life! George Plimpton claimed that he played college football for the Newfoundland Newfs. The Detroit Lions were not amused. I was taken in by the Sidd Finch hoax. I think that George Plimpton lived life well and gracefully. I am not surprised that Robert Kennedy was his friend. If this be (fair & balanced) admiration, so be it.

[x NYTimes]

George Plimpton, Author and Editor, Dies at 76

By RICHARD SEVERO

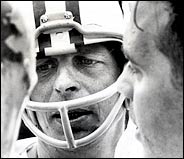

George Plimpton in 1963 as a third-string quarterback with the Detroit Lions, an experience he chronicled in Paper Lion.

George Plimpton, the New York aristocrat and literary journalist whose career was a happy lifelong competition between scholarly pursuits and madcap attempts — chronicled in self-deprecating prose — to try his hand at glamorous jobs for which he was invariably unsuited, died at his home in Manhattan. He was 76.

The cause of death was not immediately known, but Mr. Plimpton's agent, Timothy Seldes, said it was most likely a heart attack.

Mr. Plimpton, a lanky, urbane man possessed of boundless energy and perpetual bonhomie, became, in 1953, the first (and principal) editor of The Paris Review. A cultural force and ubiquitous presence at book parties and other gala social events, he was tireless in his commitment to the serious contemporary fiction the magazine publishes.

Easily identifiable in later years by his thatch of silver hair and always by his cheery, lockjaw delivery, Mr. Plimpton was a familiar figure, ranging above other guests at the restaurants, saloons and weekend destinations where blue-blood New York overlapped with the New York of the famous and the creative.

All of this contributed to the charm of reading about Mr. Plimpton's career as dilettante par excellence — "professional" athlete, stand-up comedian, movie bad guy, circus performer and many other trades — which he described elegantly in nearly three dozen books.

As a boxer, he had his nose bloodied by Archie Moore at Stillman's Gym in 1959. As a major league pitcher, he became utterly exhausted and couldn't finish the inning at an exhibition game between National and American League all-stars in 1959 (though he managed to get Willie Mays to pop up). And as a "professional" third-string quarterback with the Detroit Lions, he lost roughly 30 yards during a scrimmage in 1963. On Sunday Mr. Plimpton was in Detroit for a 40th-anniversary reunion with the players who once lined up with "a 36-year-old free-agent quarterback from Harvard."

He also tried his hand at tennis (Pancho Gonzalez beat him easily), bridge (Oswald Jacoby outmaneuvered him) and golf. With his handicap of 18, he lost badly to Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus.

In a brief stint as a goal tender for the Boston Bruins, he made the mistake of using his gloved hand to catch a flying puck, which caused a nasty gash in his pinky. He failed as an aerialist when he tried out for the Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers Circus. As a symphonist, he wangled a temporary percussionist's job with the New York Philharmonic. He was assigned to play sleigh bells, triangle, bass drum and gong; he struck the last so hard during a Tchaikovsky chestnut that Leonard Bernstein, who was trying to conduct the piece, burst into applause.

That was Mr. Plimpton, the popular commercial writer. His alter ego was as the unpaid editor of The Paris Review, an enduring, chronically impoverished quarterly, founded in 1952 by Peter Mathiessen and Harold L. Humes, who asked him to edit it. He did so from 1953, when publication began, until the end of his life.

Over the years, the magazine gained a loyal following for its dedication to new fiction. Among the many authors it published were Terry Southern, Philip Roth, T. Coraghessan Boyle, Mona Simpson, George Steiner and V. S. Naipaul. It also introduced works by Donald Barthelme, Italo Calvino, Rick Moody and David Foster Wallace.

The Paris Review was a must-read as well for its interviews with established writers: Archibald MacLeish, Pablo Neruda, Gore Vidal, Joan Didion, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Ernest Hemingway and scores more. Mr. Plimpton interviewed some, including Hemingway, personally.

Some years ago, Gay Talese, a longtime friend of Mr. Plimpton's, wrote about The Paris Review in an essay called "Looking for Hemingway." Describing the review's earliest days in Paris, Mr. Talese wrote that the editors, chiefly Mr. Plimpton, turned out a successful magazine because "they avoided using such typical little-magazine words as `zeitgeist' and `dichotomous,' and published no crusty critiques about Melville or Kafka, but instead printed the poetry and fiction of gifted young writers not yet popular."

Later, after Mr. Plimpton and his friends had moved to New York and become known variously as "the Quality Lit Set," "the East Side Gang" and "the Paris Review Crowd," they gathered regularly at the Plimpton apartment, Mr. Talese wrote, "for the liveliest literary salon in the city."

As a "participatory journalist," Mr. Plimpton believed that it was not enough for writers of nonfiction simply to observe; they needed to immerse themselves in whatever they were covering. For example, football huddles and conversations on the bench constituted a "secret world," he said, "and if you're a voyeur, you want to be down there, getting it firsthand."

And he didn't always fall on his face. One night in 1997 (too old by then to engage in strenuous contact sports), he showed up at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, which was then having its amateur night. He announced that he was an amateur, and when asked what he was going to play, replied, "the piano." He knew only "Tea for Two" and a few other tunes, but played his own composition, a rambling improvisation he called "Opus No. 1." The audience adored him, and the charmed judges gave him second prize.

In 1983 he scored another success when he volunteered to help the members of the Grucci family plan and execute a fireworks display to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Brooklyn Bridge. They accepted his kind offer, and he did his job without destroying himself or any of the Gruccis. For a time, he was regarded as New York City's fireworks commissioner, the bearer of a highly unofficial title with no connection to the city government. In 1984 he wrote a book on his love of the rockets' red glare, called "Fireworks: A History and Celebration."

He was given to practical jokes. While he was a writer for Sports Illustrated, he invented a fictitious pitcher, Sidd Finch, whom he described as a Buddhist with a 168-mile-an-hour fastball. This unlikely soul became the centerpiece of his 1987 novel, The Curious Case of Sidd Finch.

Mr. Plimpton was first married in 1968 to Freddy Medora Espy, a photographer's assistant. They had two children, Medora and Taylor, who survive him. The marriage ended in 1988. In 1991 he married Sarah Whitehead Dudley, 26 years his junior, who also survives him, along with their twins, Laura and Olivia.

George Ames Plimpton was born on March 18, 1927, in New York, the son of Francis T. P. Plimpton, a corporate lawyer (he was one of the early partners in the firm that is now Debevoise & Plimpton) who became a United Nations ambassador. His mother was the former Pauline Ames. His grandfather, George A. Plimpton, had been a publisher. The family traced its roots in this country to the arrival of the Mayflower.

Mr. Plimpton was educated at Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard and Cambridge. His career at Harvard, where he studied literature, was interrupted in 1945. He spent two years in the Army, then returned to college and received his bachelor's degree in 1950, although he always regarded himself as a member of the class of 1948. He earned a second baccalaureate degree at Cambridge, where he also earned a master's.

Mr. Plimpton's career included teaching at Barnard College from 1956 to 1958 and editing and writing at Horizon magazine (1959 to 1961) and at Harper's magazine (1972 to 1981). He also contributed material to Food and Wine magazine in the late 1970's. In the late 60's, he was seen frequently as a host or a guest on several television shows, and still later, he made some commercials for De Beers diamonds.

He had been inspired as a youth by Paul Gallico, an author and sports writer for The Daily News. Mr. Gallico believed so much in participatory journalism that he once had a brief encounter with the heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey.

"What Gallico did was to climb down out of the press box," Mr. Plimpton said, creating "a wonderful description of what it feels like to be knocked about by a champion." The only problem with Mr. Plimpton's similar match with Archie Moore, set up by Sports Illustrated, was that Mr. Plimpton wept after Mr. Moore bloodied his nose. He called it a "sympathetic response."

Many of Mr. Plimpton's books dealt with his adventures, most notably Out of My League (1961), on baseball; Paper Lion (1966), on football; and The Bogey Man (1968), on golf. Ernest Hemingway read Out of My League and declared that it was "beautifully observed and incredibly conceived, his account of a self-imposed ordeal that has the chilling quality of a true nightmare. It is the dark side of the moon of Walter Mitty."

The Walter Mitty reference was picked up by several critics, but Mr. Plimpton's exploits were not really like those of Mitty, James Thurber's fictitious daydreamer. For while Mitty only imagined that he was doing heroic things, Mr. Plimpton wasn't imagining anything.

Not all of Mr. Plimpton's writings dealt with his guises. In 1955 he wrote a children's book, The Rabbit's Umbrella. He also edited American Journey: The Times of Robert F. Kennedy (1970). He was a friend of the Kennedy family and was with Robert Kennedy the day he was shot to death by Sirhan Sirhan in Los Angeles. Mr. Plimpton said Mr. Sirhan "seemed composed and peaceful" after Kennedy died.

In 1997 he also wrote an unconventional biography of Truman Capote, in which he meshed the techniques of oral history and traditional biography. And in 2002, joined by Terry Quinn, he created Zelda, Scott and Ernest, a dramatization of the correspondence between F. Scott Fitzgerald; his wife, Zelda; and Hemingway. It was produced in Paris.

Mr. Plimpton made it into movies and television, too. He was an extra — a Bedouin — in Lawrence of Arabia in 1962, and in Rio Lobo (1970) he played a crook who is shot dead by a heroic John Wayne. When the movie of Paper Lion was made in 1968, Alan Alda played Mr. Plimpton, who had a minor part himself. For a time, Mr. Plimpton also had a recurring role as Dr. John Carter's wealthy grandfather on E.R. He used to say he had been pegged as "the Prince of Cameos."

Last year Mr. Plimpton was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Perhaps his career was best summarized by a New Yorker cartoon in which a patient looks at the surgeon preparing to operate on him and demands, "How do I know you're not George Plimpton?"

Copyright © 2003 The New York Times Company