When if's and but's are candy and nuts, Dub'll have a helluva Christmas. The boy president has exhausted the political capital of 9/11. He's not a wartime president, he's an idiot president. The writing is on the wall. The only tragedy is the loss of life among our troops in that spot of hell known as Iraq. The historical reality is that the only popular war in the U.S. was "the good war," aka WWII. Dub tried like hell to put an act as a WWII-style "war leader," but that dog won't hunt. If this is (fair & balanced) history, so be it.

Have Americans Usually Supported Their Wars?

By HNN Staff

It has seemed to come as a bit of a shock to the Bush administration that Americans are turning against the war in Iraq. Just as administration officials weren't prepared for the fierce resistance that developed to the American occupation of Iraq, neither were they prepared for a change in public opinion at home as the war dragged on. Cindy Sheehan's galvanizing protests outside the president's vacation home caught officials by surprise.

But throughout American history there has always been significant opposition to war. New England states threatened to secede from the union during the War of 1812, which severely hampered the trade carried in New England ships. The Mexican-American War was opposed by leading Whigs including Congressman Abraham Lincoln. During the Civil War President Lincoln faced the opposition of the Copperheads, many of whom he had thrown in jail. The Spanish-American War triggered a robust anti-imperialist movement led by William Jennings Bryan.

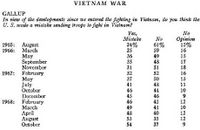

In the twentieth century, as Hazel Erskine demonstrated in her widely cited 1970 article, "Was War a Mistake?" (Public Opinion Quarterly), "the American public has never been sold on the validity of any war but World War II." She noted that as of 1969--a year after the Tet Offensive and the brief invasion of the American embassy in Saigon--"in spite of the current anti-war fervor, dissent against Vietnam has not yet reached the peaks of dissatisfaction attained by either World War I or the Korean War."

Reviewing the wars of the 20th century, she noted:

In answer to quite comparable questions, in 1937 64 per cent called World War I a mistake, in 1951 62 per cent considered Korean involvement wrong, whereas in 1969 burgeoning anti-Vietnam dissent nationwide never topped 58 per cent.

Her charts demonstrated the extent of American opposition to war:

Gallup Poll — WWI

Click image to enlarge

Gallup Poll — WWII

Click image to enlarge

Gallup Poll — Korean Conflict

Click image to enlarge

Gallup Poll — Vietnam Conflict

Click image to enlarge

Copyright © 2005 History News Network