Joel, 22 months & Alex, 1+ month [Click on image to enlarge.] If this is (fair & balanced) Grandpa pride, so be it.

Highlight/right-click anything for Google info.

Search the blog: a search window is provided at the top of the left-side menu.

Blog Rationale: The Internet is a vast library; this blog's the best Reserve Room in that library.

Follow This Blog via E-Mail (below the blogger's profile).

Text Color/Font Code: GREEN text is written by this blogger; BROWN text (different font) is the posted article itself.

I want to see Kerry wipe that frat-boy smirk off W's face. If this is (fair & balanced) outrage, so be it.

[x American Prospect]

Debate School: Ten things John Kerry should do to change the dynamic of the race.

By David J. Sirota

Perhaps no candidate in the last 20 years has had so much riding on the presidential debates as John Kerry does. Bludgeoned by merciless attack ads and a well-oiled right-wing spin machine, Kerry is still a virtual unknown to many Americans, with few having a clear picture of who he is or what he stands for. This din of distracting issues and cheap personal attacks has also, by design, deprived voters of a crisp and cogent case against the current administration.

Yet, as testament to George W. Bush’s inherent weaknesses, Kerry still remains neck and neck with the incumbent in the polls. That means that the upcoming debates represent his best chance yet to go from undefined challenger to legitimate alternative. To get there, here are the top 10 things he must do:

1. Make your Iraq vote an indictment of Bush. Bush has ridiculed Kerry for having a nuanced position on Iraq, but the bottom line is undeniable: Kerry has been consistent in saying that his vote was to give Bush the authority to use force -- not an endorsement of recklessly misusing that authority and misleading America, as the White House did. Sure, his answers on the campaign trail have been less than perfect. But he can still transform his Iraq vote from an albatross into a weapon by making it all about White House credibility. The question is not why John Kerry voted to trust his commander in chief in the aftermath of September 11; most Americans wanted to trust the president, especially on issues of weapons of mass destruction. The real question is why Bush abused that trust, lied to America about the intelligence, and plunged the country into war on false pretenses.

2. Connect the Vietnam experiences to Iraq. Critics charge that Kerry’s focus on his Vietnam War experience was a miscalculation, especially after the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth smears. They also claim that Bush’s and Dick Cheney’s records of evading combat are irrelevant. Both statements may be true now, but they do not have to be from this point forward. Kerry can transform Vietnam from non sequitur to salience by making a very simple argument: Bush’s careless postwar Iraq plan, which has needlessly put troops in harm’s way, is a direct consequence of his lack of combat experience and refusal to take military service seriously. Bush hid behind the protection of his personal security detail, told terrorists to “bring them on” [the attacks], and then refused to provide American soldiers with adequate body armor. Only someone who has never seen the barrel of an enemy's machine gun -- and yet brags about a spotty National Guard record -- could be so reckless. Kerry, on the other hand, has the shrapnel in his leg to prove that he really understands the gravity of putting troops' lives on the line, and that he would be more serious and thoughtful before doing so.

3. Demand answers about specific national-security decisions. Over the last year, evidence has emerged that has called into question all of Bush's rhetoric about being tough on terrorists. We have learned the administration has fewer intelligence operatives tracking Osama bin Laden than before 9-11; the Bush Treasury Department has five times as many agents investigating Cuban embargo violations than it does tracking al-Qaeda’s finances; the White House three times rejected military plans to kill Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the terrorist behind much of the insurgency in Iraq; and the neoconservative-dominated Pentagon secretly moved Special Forces off the hunt for al-Qaeda in 2002 so they could prepare for an Iraq invasion. Kerry should ask specific questions about why these decisions were made, as they add up to an airtight case that Bush is not serious about defending America.

4. Use the word “Halliburton” at least 15 times a debate. Cheney’s oil company has become a symbol to America about what is wrong with having a government run by people willing to put corporate interests above the public interest. Not only does Halliburton raise serious improprieties about the vice president coordinating no-bid contracts for a company he still owns holdings in and receives compensation from, it evokes all of the other White House favors for corporate campaign donors.

5. Talk about how the Bush-Saudi relationship compromises America's national security. The Achilles’ heel of Bush's image as an advocate for democracy and as a no-nonsense terrorist fighter is his all-too-close relationship with the Saudi royal family. As author Craig Unger writes, "Never before in history has a [president] been so closely tied financially and personally to the ruling family of another foreign power. Never before [have] a president's fortunes and public policies been so deeply entwined with another nation." The Saudis, of course, are not just your run-of-the-mill dictators; they’ve been investigated for funding the 9-11 terrorists, have refused to fully cooperate in the global war on terrorism, and are known to underwrite anti-American Islamic fundamentalism. Yet from classifying a congressional report about potential Saudi ties to terrorism to deploying crony James Baker to defend the Saudis in lawsuits by the 9-11 victims’ families, the White House has done everything possible to shield these despots from scrutiny. And make no mistake about it. This issue has political resonance. Focus groups during Kerry’s speech at the Democratic national convention indicated a spike in support for the Massachusetts senator when he said that U.S. policy should not be dictated by the Saudi royal family.

6. Remind people about Bush's secret war on working families. In talking about the economy, Kerry has focused mostly on tax cuts, allowing Bush to muddle the issue by claiming that this administration’s tax policy helps the middle class (it does not, but it makes for good rhetoric). During the debates, Kerry should buttress his tax arguments with a critique of other, even more offensive actions that the White House has taken to stiff ordinary Americans. During a recession, why did Bush sign a report endorsing outsourcing? Why is the Bush Commerce Department encouraging U.S. companies to move to China? Why is the Bush Labor Department giving companies tips about how to avoid paying overtime? Why did the president slip a provision into the Medicare bill giving new subsidies for companies to slash retirees’ health benefits? Why did Bush oppose bipartisan legislation cutting off federal loan guarantees to companies shipping jobs overseas? Unlike a tax debate that can be blurred by "fuzzy math," Bush cannot lie his way out of these questions.

7. Connect Bush's money to his decisions. Polls show that the public knows Bush is closely aligned with big business. Yet unless those ties are connected to specific policy decisions, Americans seem willing to accept that reality as just another staple of modern politics. That is why when Kerry discusses Bush's record, he must detail who Bush was paying back when he made decisions. $7.5 million from Wall Street, for example, bought a weak corporate-reform bill and a lax attitude toward offenders like Enron; $5 million from the health-care industry bought a Medicare bill that weakens the program while enriching the HMOs and big drug companies; $2 million from the energy industry bought an energy bill that would give away billions in new tax credits to oil companies (already fleecing billions from skyrocketing gas prices). The list goes on. The point is for Kerry to be very specific about cause and effect.

8. Stop pretending you never served in the Senate. Many Americans still know almost nothing of Kerry’s Senate record beyond what has been force fed to them via Bush television ads. That is partially due to Karl Rove’s effective campaign of taking votes out of context to make Kerry look like a serial flip-flopper. But it is also because Kerry has avoided promoting his accomplishments. He should quit being so reticent. For instance, Kerry can speak forcefully about how in the early 1990s -- before fighting terrorism was in vogue -- he overcame opposition from both political parties to bring down the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) after he discovered its ties to terrorists like Abu Nidal and Osama bin Laden. (At almost the very same time of Kerry’s investigation, Bush was doing business with a BCCI joint venture.) Kerry could also talk forcefully about his efforts to raise fuel-efficiency standards -- a courageous position on energy security that earned him powerful enemies in the oil and auto industry and that contrasts with Bush’s corporate-driven agenda. Or he could pick something else. The point is for him to stop ignoring his record, because it makes it look like he does not have one. In fact, he does.

9. Take a controversial position. Bush right now does not have any of the news or policy positions on his side. The war in Iraq is raging out of control, the economy is sagging, and polls have shown that the public has serious questions about Bush's foreign and economic policies. In spite of this, he remains a viable candidate. How? Because, as a new CBS poll illustrates, Bush is perceived as willing to take tough positions and say what he believes. Kerry, on the other hand, has run a risk-averse campaign, trying to avoid positions that are not sure winners. But rather than help him avoid danger, this all-things-to-all-people strategy has allowed him to be portrayed as weak-willed, prevaricating, and opportunistic. In the debate, he can parry this criticism by going out on a limb and taking a principled position on a divisive issue. It makes no difference what issue he chooses; it matters that he displays a willingness to accept the political consequences of his personal convictions. If he needs proof that such chutzpah works, he need only remember what vaulted him to prominence in the first place: courageous opposition to the Vietnam War.

10. Don't try to be something you are not. There has always been talk that Kerry comes off as "aloof" or not "likable." He has overcompensated with various stunts, like appearing on Jay Leno’s show riding a Harley, or taking reporters with him while he buys a jockstrap. In the debate, he should drop the pretense that he has to be anything other than himself. He should not try to be funny or folksy; that will come off as false. Instead, he can turn his purported weaknesses into strengths that contrast with Bush. He is not aloof; he is a thoughtful leader who can see shades of gray in a world that is never black and white. Nor is he unlikable; he is a serious person for serious times.

David Sirota is the director of strategic communication at the American Progress Action Fund, a progressive advocacy organization in Washington, D.C.

Copyright © 2004 by The American Prospect, Inc

Stanley Fish is still teaching freshman composition after stepping down as Dean of Arts & Sciences at Illinois-Chicago? Why? I shudder to think about the reasoning I would witness in a freshman history class at my former place of labor (Collegium Excellens). Most of the knuckle-dragging, drooling students in my history classes would be supporting W. (Thankfully, most of them don't vote.) It just gets grimmer and grimmer. If this is (fair & balanced) euphony, so be it.

[x The New York Times]

The Candidates, Seen From the Classroom

By STANLEY FISH

CHICAGO

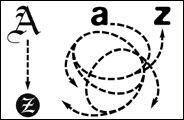

Groan! W's speech pattern (left) and Kerry's speech pattern (right).

In an unofficial but very formal poll taken in my freshman writing class the other day, George Bush beat John Kerry by a vote of 13 to 2 (14 to 2, if you count me). My students were not voting on the candidates' ideas. They were voting on the skill (or lack of skill) displayed in the presentation of those ideas.

The basis for their judgments was a side-by-side display in this newspaper on Sept. 8 of excerpts from speeches each man gave the previous day. Put aside whatever preferences you might have for either candidate's positions, I instructed; just tell me who does a better job of articulating his positions, and why.

The analysis was devastating. President Bush, the students pointed out, begins with a perfect topic sentence - "Our strategy is succeeding"- that nicely sets up a first paragraph describing how conditions in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia four years ago aided terrorists. This is followed by a paragraph explaining how the administration's policies have produced a turnaround in each country "because we acted." The paragraph's conclusion is concise, brisk and earned: "We have led, many have joined, and America and the world are safer."

It doesn't hurt that the names of the countries he lists all have the letter "a," as do the words "America" and "safer." He and his speechwriters deserve credit for using the accident of euphony to give the argument cohesiveness and force. There is of course no logical relationship between the repetition of a sound and the soundness of an argument, but if it is skillfully employed repetition can enhance a logical point or even give the illusion of one when none is present.

The students also found repetition in the Kerry speech, about the outsourcing of jobs, but, as many pointed out, when Mr. Kerry repeats the phrase "your tax dollars" it is because he has become lost in his own sentence and has to begin again.

When he finally extracts himself from that sentence, he makes two big mistakes in the next one: "That's bad enough, but you know there's something worse, don't you?" No, Senator Kerry, we don't know - because you haven't told us. He is asking people to respond to a point he hasn't yet made and, even worse, by saying "don't you?" he is implying they should know what this point is before he makes it. As a result, the audience is made to feel stupid.

And if that wasn't "bad enough,'' consider his next two sentences. Up until now Mr. Kerry's point (insofar as you could discern one) had been that current tax policies reward companies for moving their operations overseas. But he goes on to add, "it gets worse than that in terms of choices." The audience barely has time to wonder what and whose choices he's talking about before it is entirely disoriented by the declaration that "today the tax code actually does something that's right." Excuse us, but how can getting something "right" be "worse"? It turns out that there is an answer to that question later in the speech - Mr. Kerry says that while the tax code now rewards companies that export American products, Mr. Bush wants to eliminate that good incentive - but it comes far too late for an audience discombobulated by the sudden and unannounced change in the argument's direction.

Senator Kerry, my students observed with a mix of solemnity and glee, has violated two cardinal rules of exposition: don't presume your audience has information you haven't provided, and always pay attention to the expectations of your listeners. They also felt that when he concludes by declaring that "when I'm president of the United States, it'll take me about a nanosecond to ask the Congress to close that stupid loophole," he undercuts the dignity both of his message and of the office he aspires to by calling the loophole "stupid" (instead of "unconscionable" or "unprincipled" or even "criminal"). "Stupid," one student said, is not a "presidential kind of word."

So what? What does it matter if Mr. Kerry's words stumble and halt, while Mr. Bush's flow easily from sentence to sentence and paragraph to paragraph? Well, listen to the composite judgments my students made on the Democratic challenger: "confused," "difficult to understand," "can't seem to make his point clearly," "I'm not sure what he's saying," and my favorite, "he's kind of 'skippy,' all over the place."

Now of course it could be the case that every student who voted against Mr. Kerry's speech in my little poll will vote for him in the general election. After all, what we're talking about here is merely a matter of style, not substance, right? And - this is a common refrain among Kerry supporters - doesn't Mr. Bush's directness and simplicity of presentation reflect a simplicity of mind and an incapacity for nuance, while Mr. Kerry's ideas are just too complicated for the rhythms of publicly accessible prose?

Sorry, but that's dead wrong. If you can't explain an idea or a policy plainly in one or two sentences, it's not yours; and if it's not yours, no one you speak to will be persuaded of it, or even know what it is, or (and this is the real point) know what you are. Words are not just the cosmetic clothing of some underlying integrity; they are the operational vehicles of that integrity, the visible manifestation of the character to which others respond. And if the words you use fall apart, ring hollow, trail off and sound as if they came from nowhere or anywhere (these are the same thing), the suspicion will grow that what they lack is what you lack, and no one will follow you.

Nervous Democrats who see their candidate slipping in the polls console themselves by saying, "Just wait, the debates are coming.'' As someone who will vote for John Kerry even though I voted against him in my class, that's just what I'm worried about.

Stanley Fish is dean emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Copyright © 2004 The New York Times Company

I listen to the BBC World News Service regularly. The Internet NPR station in San Antonio (Texas Public Radio—KSTX-FM—89.1 Mhz—on the campus of San Antonio College) doesn't have enough transmitter power to provide a clear signal in Geezerdom (Sun City, TX), but Internet radio overcomes that problem. Texas Public Radio provides the BBC World News Service daily. I haven't watched network news in years and I don't plan to go back. I watch less and less cable news, too. Too much perky cuteness will bring on diabetes. Even Greta Van Susteren (gasp) underwent a facelift for Fox News. If this is (fair & balanced) Ratherphobia, so be it.

[x British Journalism Review]

For many, British is better

by Christian Christensen

Since the start of the war in Iraq, much has been made of the fact that a significant number of Americans are turning to British news sources – such as The Guardian and the BBC – for information regarding the conflict. Figures from The Guardian, for example, indicate that about 40 per cent of the newspaper’s online readers are located in the United States. Similarly, audiences for BBC World News bulletins aired on the U.S. Public Broadcasting System (PBS) increased by almost 30 per cent during the first weeks of the war. The BBC website has also seen a dramatic increase in the number of users from the United States, as even a cursory glance at BBC message boards and chat rooms will indicate. These developments have been cited by media critics as evidence of a broader dissatisfaction on the part of the American public with the state of the press in the United States. The highly commercialised and nationalistic nature of the U.S. news media, so the argument goes, in addition to an uncomfortably close relationship between the press and the military, has made it impossible for the average citizen to get “objective” or “unbiased” information about events in Iraq.

Before September 11, CNN was the flagship international news channel, with coverage of Operation Desert Storm in 1991 solidifying its status. In light of recent events, however, it now seems plausible that the BBC could replace CNN as the definitive word in international 24-hour satellite news. While CNN news programmes – with their pert, perfect-hair-and-teeth presenters – leave many with a saccharin taste in the mouth, there is no denying that the organisation always seemed to be in the right place at the right time for the right pictures. Of course, many of the outstanding visuals obtained by CNN could perhaps be attributed to the slightly better-than-average relationship cultivated by CNN with powerful individuals in certain countries.

Let us be clear about one thing: CNN has never obtained huge ratings internationally, or in the U.S. Much of the mythology surrounding Ted Turner’s baby is self-created, and the marketing of the CNN brand has, more often than not, been more effective than the actual product. CNN’s ratings in the U.S. – home turf for the channel – are dwarfed by those of the three national networks (NBC, ABC and CBS). While between five and eight million households tune into the main evening news on one of the three networks, the Nielsen Media Research company revealed that in early 2004 CNN had trouble attracting 500,000 viewers during an average day, let alone for one programme. To make matters worse, CNN is also being trounced in the U.S. cable market (by a ratio of two viewers to one) by the ultra-conservative Fox News Channel.

In many ways, the arrival of Rupert Murdoch’s nationalistic, bombastic Fox News has been a harsh blow for CNN, and could account for the upswing in interest in UK news outlets in the U.S. While making CNN look almost statesmanlike in comparison, Fox News has tarred CNN, and many other U.S. news outlets, with a broad “ugly American” brush. Fox is like the loud, brash American tourist who tramples through London: we know we should not see this crude stereotype as representative of all Americans, but it is very tempting. The unapologetic, unquestioning nationalism of Fox News has, fairly or unfairly, become a symbol of what is wrong with journalism in the United States. To a certain extent, and to certain people, U.S. news media such as Fox also reflect what is wrong with American foreign policy: an excessive focus on U.S. interests above all other interests, an uncritical attitude toward unilateral power, and a near-religious belief in the infallibility of the free market.

What has disappointed many Americans is not that news outlets have openly supported the war (many have not), but that most have been so relatively timid and uncritical. The scandalous, uncontested and lucrative Iraq reconstruction contracts awarded to Halliburton (former executive: U.S. vice-president Dick Cheney) by the Bush administration, for example, would be enough to bring down governments in other nations. In the U.S. the contracts have raised knowing eyebrows, but not the wrath of the mainstream media. A typical and very effective ploy of the political right in the United States to keep critique of the war to a minimum has been to attack the supposed “liberal bias” of the mainstream news media. Or, alternatively, sceptical journalists who dare to question national policy are accused of “supporting the terrorists” or “hurting the morale” of the troops. The logic of such attacks beggars belief, especially when considering that the corporate owners of the four television networks, the major suppliers of news in the U.S. are the multi-billion dollar conglomerates Disney (ABC), General Electric (NBC), Viacom (CBS) and News Corp (FOX) – hardly breeding grounds for Marxist-Leninist reactionaries.

Following the 1991 Gulf War, the long-time CBS news anchor Dan Rather was asked about the relationship between patriotism and journalism during times of conflict. Without hesitation, Rather stated that, as an American, when it came to the crunch he would always be on the side of the American troops – this, from the anchor of one of the most-watched news programmes in the United States. Despite the disturbing implications of Rather’s comments for U.S. democracy, this unashamed lack of objectivity or neutrality (the supposed hallmarks of American journalism) garnered little or no media attention. Not much has changed over the past 13 years. In the current U.S. media environment, unquestioning patriotism is a virtue, while sceptical critique is a vice.

A positive image

British news outlets have, to a limited extent, cashed in on this situation. It is not without a dash of irony that many of the attributes that made the BBC the brunt of so much criticism in the past – stoicism, paternalism, a certain degree of pompous self-righteousness – have come back into fashion. The events in the days following the release of the Hutton report illustrate the point. While many media insiders considered the BBC handling of the Gilligan affair to be incompetent, the image of the BBC among the general public post-Hutton, both inside and outside the UK, was generally positive. Many Americans were shocked by the openness with which the BBC dealt with the fallout. The appearance of Greg Dyke on the evening news to answer questions over the bungling of the affair was proof-positive to many that the BBC works to a different standard than news outlets in the United States.

To illustrate the point, I tried to imagine one of the board members of Disney (owners of ABC) or General Electric (owners of NBC) going on their own evening news programmes to get a grilling from one of his/her own journalists. I couldn’t. Over the past year I have seen numerous U.S. politicians, advisors and military personnel interviewed on the BBC by the likes of Tim Sebastian or Jeremy Paxman. In almost every case, the interviewee was clearly unnerved by the aggression of the interviewer and the tone of the questions. Officials from the U.S. are simply not used to having either their word or their authority questioned. While a full-on Paxman inquisition might be old hat, and occasionally irritating, to viewers in the UK, to many Americans, a seasoned politician developing sweat just below the hairline is an unusual, if not refreshing sight. What makes the BBC coverage all the more stimulating for certain American audience members is the fact that these hard-hitting interviews are mixed with relatively levelheaded field reporting and news presentation.

The case of The Guardian is somewhat different. Unlike the BBC, it has a clear position vis-à-vis the Iraq conflict. There is no veneer of pseudo-neutrality, and that is perhaps the major selling point to American readers. As with the BBC, The Guardian can be accused of smug self-righteousness, yet the occasionally preachy nature of the newspaper affords readers the opportunity to take a position on what they read. No one is under any illusion about what The Guardian stands for, yet its stories are generally well researched and well written, and its opinion columns clear and to the point. Newspapers such as The Guardian also allow readers in the United States the chance to read stories containing perspectives otherwise unavailable to them in the domestic market. A frequently cited example by readers from the U.S. is the more balanced coverage in The Guardian of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

The rise in the popularity of news organisations such as the BBC and The Guardian illustrates that the “packaging” of news and information at the production end remains an important factor in influencing audience preferences. A major influence on academic media studies over the past 20 years has been the recognition that audiences can make meaning out of what they see, hear or read, regardless of the intent of the producer of the media text. In other words, one cannot assume that all audiences understand the same message in the same way, news included, nor should they be treated as mindless lumps soaking up and believing any piece of propaganda hurled in their general direction.

One problem about this line of thinking, however, is that an excessive devotion to the notion of the “empowered audience” can downplay the role of economics and politics in the production, distribution and exhibition of media texts, thus divorcing media products such as news from the ideological environments in which they are made. In this scenario, audience power could be seen to be a sufficient counterweight to economic power – an argument that comes perilously close to the crudest forms of neo-liberal thinking in which the “audience member is king”, and blameless media companies exist merely to provide stimulation. While viewers, readers and listeners are free to “decode” messages as they wish, the increased use of British news outlets suggests that some in the U.S. are, in fact, very much interested in the original “coding” of news by journalists and editors. Audiences might very well be able to “resist” unappealing messages and reinterpret them to suit their own political or ideological beliefs, but that does not necessarily mean that they want to be forced into a position to do so.

With this in mind, who are these Americans reading The Guardian online, watching the BBC on PBS, or listening to the BBC World Service? Because this phenomenon is relatively new, there is a paucity of research on the subject. An informed guess would be that these individuals are predominantly liberal, relatively affluent, university-educated Democrats. In other words, the type of people who dislike President George W Bush and were opposed the use of military force in Iraq from the start. In fact, the public broadcasting system carrying the BBC World News bulletins, PBS, is known as a haven for slightly dull, slightly middle-aged, slightly upper-middle-class east coast Democrats.

A disturbing gap

It would be both elitist and arrogant to suggest that it is only the educated anti-war crowd who are interested in British news, but it seems highly unlikely that hardcore, fundamentalist Republicans are breathlessly going online to read a Polly Toynbee column on prisoner abuse, or to download a video of Jeremy Paxman’s interview with Noam Chomsky. There is no doubt that over the past two years a sizable number of Americans have turned to outside sources of news and information. The “discovery” of the BBC and other British news outlets by segments of the American public speaks to a disturbing gap in the supply side of the U.S. news market. Despite all the hype surrounding the “democratic” nature of the free market, many in the U.S. simply cannot find the information they are looking for. Online technologies have made access to alternative sources of news much easier, enabling news consumers around the world to obtain otherwise unavailable information and perspectives.

It is important to place these developments in their proper context and to avoid the temptation to romanticise. The fact remains that mainstream news sources in the U.S. – network and cable television, newspapers, etc. – continue to dominate. The increasing audience for British news sources is an interesting development in the field of journalism, but the future is uncertain. As with all things web-related, the spectre of technological determinism looms large. A belief in the power of technology can be appealing, but should be tempered by the realisation that technology is a tool for change, not an end result. While it is also tempting for foreigners to regale organisations such as the BBC, particularly when compared to the gung-ho Fox News, it is worth remembering that every organisation must play power games. All news outlets, regardless of funding or political persuasion, are subject to political-economic pressures. The licence fee is not an act of God, and owners want profits.

While it would be nice to believe that Americans of all political stripes are surfing to the UK in search of balanced reporting, “preaching to the choir” is probably a more accurate summary of what is going on with Americans and their use of British news outlets… at the moment. If mainstream journalists in the United States continue to hug the centre rail and avoid asking difficult questions, however, this could change. Faith in the “the free market of ideas” has served the U.S. media well financially over the years, but with rapid technological developments, and the potential for an increasingly dissatisfied audience, it could come back to bite them.

Christian Christensen is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Communication at Bahcesehir University in Istanbul. His areas of research interest include international news coverage, the political economy of media and media policy. He has lived and worked in the United States (his home country), the UK, Turkey and Sweden.

© 2004 BJR Publishing Ltd.