Jennifer Fisher's take on Classic Citizens reminded me that Rodney Dangerfield in 82 years old. I hope that he gets a rimshot during his funeral. If this is (fair & balanced) drollery, so be it.

[x The Weekly Standard]

It's Not Easy Bein' Rodney

Comedian Dangerfield's autobiography is outrageous, entertaining—and surprisingly frank.

by Duncan Currie

I don't get any respect.

EVERY Caddyshack fan has a favorite line from the 1980 movie and for sheer kitsch, it's hard to trump the exclamation by millionaire loudmouth Al Czervik following the climactic scene: "Hey, everybody! We're all gonna get laid!" In and of itself, it's not that funny; it's not even a joke, really. Except that the actor playing Czervik is Rodney Dangerfield. Coming off his lips, the otherwise churlish outburst somehow seems utterly hilarious--and utterly inoffensive, so endearing is Dangerfield's persona. He has, we might say, the comedic equivalent of the Midas touch: a combination of lovable charm and impeccable delivery that turns a lame wisecrack into one of Caddyshack's most memorable utterances.

It's hard to believe now, but prior to Caddyshack Dangerfield wasn't a big movie star. Nor, for that matter, did he make any real money from the film. As he explains: "It actually cost me money to do Caddyshack. I had to give up at least a month's work in Vegas. So it cost me $150,000 to do the movie, and they only paid me $35,000. People think I've made a fortune off reruns, merchandising, and stuff like that, but I got nothing: $35,000; that was it. My part in Caddyshack did get me into doing movies, though, so I guess it paid off in the end."

He relates that story--and many more--in his new autobiography, It's Not Easy Bein' Me: A Lifetime of No Respect but Plenty of Sex and Drugs. The book is an impressive achievement. It manages to be at once a touchingly frank memoir, a droll (and often outrageous) narrative, and a how-to guide for young comedians. It's alternately light-hearted and sad, hysterically entertaining and surprisingly poignant. Dangerfield has lived a rich life, a complete life--and a long life. He is now 82 years old. "According to statistics about men in their eighties," he writes in the introduction, "only one out of a hundred makes it to ninety. With odds like that, I'm writing very fast. I want to get it all done. I mean, I'm not a kid anymore, I'm getting old. The other night, I was driving, I had an accident. I was arrested for hit-and-walk."

Dangerfield is a throwback: a stand-up comic whose routine consists almost purely of old-fashioned (and timeless) one-liners. (Indeed, one of his earliest show-biz idols was Henny Youngman: "His act was laugh after laugh after laugh--boom-boom-boom.") His humor has always been largely self-deprecating--replete with gibes about his sex life, his looks, his age, and, of course, his perpetual inability to get some "respect" from his relatives, his friends, his wife, etc. (Three samples: "I'm not a sexy guy. I went to a hooker. I dropped my pants. She dropped her price." "My uncle's dying wish, he wanted me on his lap. He was in the electric chair." "I tell ya, my wife likes to talk during sex. Last night, she called me from a motel.")

In 82 years, Rodney's told a lot of jokes. One is reminded of Mark Steyn's observation about Bob Hope: that he "made more people laugh than anyone in history." Dangerfield isn't too far behind. Indeed, it's probably not unfair to say that, among comedians, he has made fun of himself more than anyone in history.

But success wasn't easy to come by for the Long Island native. Born Jacob Cohen on November 22, 1921, Dangerfield endured a fairly nightmarish childhood. His father, a vaudeville performer, was rarely home--"I figured out that during my entire childhood, my father saw me for two hours a year"--so his mother raised him; although "raised" is perhaps too charitable. She was a cold, bitter woman, totally devoid of maternal instincts. She regularly forgot her son's birthday, never tucked him into bed at night, and generally treated him as an abject burden. "I never got a kiss, a hug, or a compliment," he writes. "I guess that's why I went into show business--to get some love. I wanted people to tell me I was good, tell me I'm okay. Let me hear the laughs, the applause. I'll take love any way I can get it."

Dangerfield has of course gotten plenty of love from audiences over the years--partly because he is so lovable. One senses that he realizes this--that cultivating a lovable image has been a deliberate goal of his all along. Indeed, he offers the following advice to young comedians: "From the moment you walk onstage, try to make the people like you. That's the most important thing. If they like you, you can get a big laugh with a mediocre joke. If they don't like you, you've got some serious thinking to do about your career choice."

He's also gotten a lot of comedic mileage out of his childhood pain. It produced a litany of "no respect" jokes, such as: "When I was a kid I got no respect. When my parents got divorced there was a custody fight over me . . . and no one showed up." Or: "When I was a kid, I got no respect. I was kidnapped. They sent my parents a piece of my finger. My old man said he wanted more proof."

He wrote his first joke at age fifteen and achieved mild success as a comedian in his early 20s, before his career sputtered out. At age 28, Rodney decided to quite show business and "lead a so-called normal life." He worked odd jobs in the home improvement business and got married. But his marriage soon hit the rocks, and Rodney found himself down on his luck. He also increasingly felt the pull of the stage. "I was out of show business," he explains, "but show business wasn't out of me, so I did the only thing that made sense--I created a character based on my feeling that nothing goes right." At age 40, he made a comeback.

It was at this point that he inadvertently changed his name to "Rodney Dangerfield." Early on in his comeback, he was booked to a work a club he'd played to great acclaim years before under the name "Jack Roy." Uncertain of how he'd perform after such a long layoff, he asked the club owner to introduce him under a different name. When, the night of his gig, the emcee announced "Here's Rodney Dangerfield," a somewhat nonplussed audience looked at him with confusion. To break the ice, Dangerfield explained: "Hey--if you're gonna change your name, change it!" After the show, he asked the club owner where he'd gotten the new name. "I don't know," the owner replied. "I made it up, just like that."

He was back in the saddle--and his career soon took off. He traveled around the country playing the club circuit, and boosted his celebrity with appearances on Ed Sullivan and the Tonight Show. In September 1969, Dangerfield opened his own nightclub in New York (Dangerfield's). He gradually rose to a level of mega-stardom: first on stage and then, in the 1980s, on the big screen (through movies such as Caddyshack, Easy Money, and Back to School).

Along the way, Rodney got to hang with some of the biggest names in the biz--Jack Benny, Johnny Carson, Sam Kinison, and Jim Carrey, to name a few. He shares all the wild anecdotes--holding nothing back--in this book. Rodney has become particularly close to Jim Carrey, whom he first met while working Toronto in the early 1980s. When, in 1994, the American Comedy Awards gave Dangerfield its Creative Achievement Award, Carrey introduced him and presented him with the award. "His introduction of me was one of the highlights of my life," Dangerfield writes. Carrey also penned the foreword to It's Not Easy Bein' Me, in which he calls Rodney "as funny as a carbon-based life-form can be."

A regular target of Dangerfield's humor over the years has been the medical profession. For example: "My doctor is strange. No matter where it hurts you, he wants to kiss it and make it better. After he checked me for a hernia, I had to change my phone number." Or: "I tell ya, I think doctors get too much respect. A hooker should get more respect. She's more important than a doctor. I guarantee you, at four o'clock in the morning, drunk, I'd never walk up five flights of stairs to see a doctor."

But in one of the book's most heartfelt chapters, Rodney discusses his April 2003 ordeal with brain surgery. "Although I complain about doctors," he writes, "I'm only alive today because of some very good ones." He recounts the harrowing days when he didn't know if he would have brain surgery or heart surgery or both. Dangerfield ultimately had a successful brain operation. He praises his doctors at UCLA Medical Center as "geniuses."

It's impossible to read this book without hearing Rodney's famous voice, and imagining his trademark mannerisms. You get the sense that his jokes would be funny in any country, in any language, at any time--provided the comedian telling them were able to replicate Rodney's uncanny delivery and lovable persona, which is asking a lot. He is a true American icon; his hallmark white shirt and red tie are permanently displayed at the Smithsonian.

But still, as It's Not Easy Bein' Me shows, Rodney Dangerfield was one of the all-time late-bloomers. Indeed, the uneven trajectory of his rise to fame and fortune proves emphatically that there are second acts in American life. That, as George Eliot once wrote, "It is never too late to be what you might have been."

Rodney won't be with us much longer. "I can count," he writes, "and I know my days are numbered." But, he reassures us, he's not about to go anytime soon. Why? "There are too many people out there who owe me money."

As funny as a carbon-based life-form can be? Yes he is.

Duncan Currie is an editorial assistant at The Weekly Standard.

© Copyright 2004, News Corporation, Weekly Standard, All Rights Reserved.

Wednesday, August 11, 2004

The Classic Stand-up Comic

Did JibJab.com Inspire Ben Sargent?

One of the great lines in the parody of Woody Guthrie's This Land is Kerry singing:

♫Sometimes a brain can come in quite handy....♪

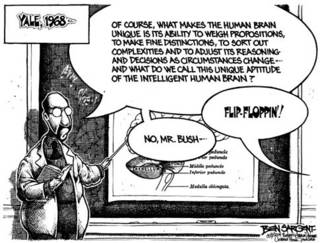

Amazingly, Imus in the Morning on MSNBC played Gregg and Evan Spiridellis' Web creation. The I-Man is not quite cutting edge this time (one month late) and MSNBC bleeped all of cusswords (favorite W forms of expression). I can envision W talking like his parody character in the Cabinet Room; I cannot imagine Kerry speaking the same way. Ben Sargent takes us back to a Yale classroom in 1968 with W (sitting on the back row, off the page). If this is (fair & balanced) non copos mentis so be it.

Ben Sargent, 8/11/04 Copyright © 2004

Austin American-Statesman [Click on

image to enlarge]

Life In Cite du Soleil, Texas

Professor Jennifer Fisher has given me a new take on life in Geezer Heaven aka Sun City, TX. Fisher, a cultural historian, nails old coots in denial. No more AARP. From now on, it's AACP (American Association of Classic Persons). I hang around with Classic (not Senior) Citizens. No more Senior Moments. My mantra: I'm having a Classic Moment." Jennifer Fisher writes about old coot charisma and I want some of that. I wonder where I can buy a bottle? The Cite du Soleil Farmers' Market on Tuesday mornings? I am going to share this rant with all of the folks around here who have Classic Charisma. Sun City (wherever) hypes itself as a community for active adults. I would rather live in Cite du Soleil— a community for classic adults. Short of that, a community for geezers or a community for old coots. Euphemisms abound and become weasel words in Williamson County. Like Fisher, I am in denial. If I can't be a Classic, then I want to be a Geezer. If I can't be a Geezer, then I want to be an Old Coot. As a Classic/Geezer/Old Coot (take your pick), my backup mantra will be (with one eye squinted) I'll tell you one damn thing prior to my rant. If this is (fair & balanced) caducity, so be it.

[x LATimes]

I'm not an aging baby boomer; I'm a "classic"

by Jennifer Fisher

The shift toward old age from middle age, that cosmic progression that baby boomers like me pretend is an eon away, hit like a landslide this summer. A friend I formerly would have described as "my age" moved to Sun City. That's the original Sun City, the planned community for grandparents, the place where a 55-and-older rule keeps out the cries of children, teenagers' loud music, people who drive faster than 10 mph and other pesky signs of life. Where geezers listen to, well, I have no idea what old people listen to, because I am not old.

Without warning, my friend Madge — that's not her name, but it might as well be — has stepped over the line from aging-baby-boomer-in-denial to senior citizen, and she's trying to drag me with her. I'd like to say that I cut her off, that she and I have nothing in common anymore. Instead, I find that we're both pretty much the same — saying the word "retirement" with quotes and agreeing that being younger than Cher matters.

But I'm not going to start calling myself a "senior" any time soon, even if it gets me a few bucks off at the movies. I'm calling instead for radical measures: The baby boomers have to rename everything to do with age; we should throw our demographic weight behind denial, or at least an ironic obfuscation of the facts.

Let's start with the ersatz honorific "senior citizen." Sure, it was once a nod in the direction of respecting our elders, very back-to-the-garden and groovy, but that was when we weren't the elders. Boomers deserve a term that really signals respect. Henceforth, we will not get old; we'll become "classic." No more "senior moments" — forgetting a word or a court date. We'll have "classic moments," as if we're so lost in philosophic inquiry we can't be bothered with details.

And for those of us who are unable to utter the word "menopause," why not call the whole mess "shifting gears"? That suggests you're still going somewhere, just at a different speed.

It's not as though the renaming strategy hasn't been discovered by marketing types, the ones who put cake into the shape of muffins and called it "health food." When it comes to selling aging, Madison Avenue mavens have been quick off the mark. Take bifocals, those old-fogy split-lens glasses. Turns out that anyone who hits 40, no matter how hip they feel, can't read without them. So someone made bifocal prescriptions invisible and called them "progressives." We're not old, satisfied customers now think, we're progressive — and we'll pay anything to keep feeling that way.

Evidently, the AARP also tried the renaming game a few years ago, after realizing that self-respecting baby boomers wouldn't join a club their parents belonged to. It not only started using initials (hoping no one would remember that the R stands for retired), it also designed a new magazine to replace Modern Maturity for the boomer demographic. I recall hearing that the first issue of My Generation would feature Mick Jagger, poster boy for old-coot charisma. Alas, even I would read about arthritis and 401Ks if Mick were talking about them. But the magazine didn't fly; maybe someone at AARP finally listened to "My Generation" and decided that "I hope I die before I get old" wasn't the best slogan for recruiting new members.

It's going to be hard to make old age cool, but baby boomers will give it the old college try. It's true we've attempted to ignore the aging process ever since we left our old colleges — wearing baseball caps and sneakers, having multiple careers and relationships and insisting that no rock music ever got better than the stuff we first made out to. But the fact is, old is coming. Or, as I like to say, we're all going to become classic one day.

Meanwhile, I've agreed to keep in touch with Madge, but only if I can write to her in Cite du Soleil instead of Sun City, in case someone sees the letter. She assures me that the lawn gnomes and petunias on her block are fast being replaced with Tuscan gardens that have good feng shui. But it's not enough, I tell her — the name has to change to something that doesn't point the way to dusty death.

"Dusty death"? Yikes. How about "the last log-off"? I'll keep working on it.

Jennifer Fisher (aka "Snowflake"

in the Nutcracker)

Jennifer Fisher holds a master's degree in Dance from York University in Toronto and a Ph.D. in Dance History and Theory from the University of California, Riverside. A former dancer and actor, she has previously taught at York University and Pomona College. Her book, Nutcracker Nation: How an Old World Ballet Became a Christmas Tradition in the New World, was published by Yale University Press in Fall, 2003. An assistant professor of dance at UCI (University of California at Irvine), Fisher teaches courses in dance history, fieldwork and philosophy, aesthetics and criticism.

Copyright © 2004 The Los Angeles Times