Quagmires and vampires; both suck the blood of our young. The analogy of Iraq as Vietnam is seductive. LBJ lied his way into the Vietnam conflict and Dub lied his way into the Iraq conflict. Neither conflict can be called a war because there was/has been no declaration of war. So, we slouch our way to disastrous results. If this is (fair & balanced) pessimism, so be it.

[x Policy Review]

Iraq Is Not Vietnam

By Frederick W. Kagan

When American ground forces paused briefly during the march to Baghdad in 2003, critics of the war were quick to warn of a “quagmire,” an oblique reference to the Vietnam War. Virtually as soon as it became clear that the conflict in Iraq had become an insurgency, analogies to Vietnam began to proliferate. This development is not surprising. Critics have equated every significant American military undertaking since 1975 to Vietnam, and the fear of being trapped in a Vietnam-like war has led to the frequent demand that U.S. leaders develop not plans to win wars, but “exit strategies,” plans to get out of messes.

There is no question that the Vietnam War scarred the American psyche deeply, nor that it continues to influence American foreign policy and military strategy profoundly. centcom’s strategy for the counterinsurgency effort in Iraq is an attempt to avoid making Vietnam-like mistakes. Proponents of other strategies, like “combined action platoons” or “oil spot” approaches, most frequently derive those programs from what they believe are the “right” lessons of Vietnam. It is becoming increasingly an article of faith that the insurgency in Vietnam is similar enough to the insurgency in Iraq that we can draw useful lessons from the one to apply to the other. This is not the case. The only thing the insurgencies in Iraq and Vietnam have in common is that in both cases American forces have fought revolutionaries. To make comparisons or draw lessons beyond that basic point misunderstands not only the particular historical cases, but also the value of studying history to draw lessons for the present.

Vietnam

An insurgency was underway in Vietnam for nearly two decades before Lyndon Johnson committed large numbers of American ground forces to the fight in 1965. The U.S. had nevertheless maintained hundreds and then thousands of “advisors” there for years before that in an effort to help the South Vietnamese government of Ngo Dinh Diem fight off an attempt to remove him that had both internal and external components. The Viet Cong was a terrorist/guerrilla force recruited from within South Vietnam and operated there. It was heavily supported by the communist government in North Vietnam, which sent advisors, equipment, and supplies, and which provided a safe haven. Ho Chi Minh’s government also supplied troops, however, and the first major battle U.S. forces in Vietnam fought on their own (now immortalized in print and on the screen as We Were Soldiers Once . . . and Young) was the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley; the enemy were North Vietnamese soldiers.

The presence of North Vietnamese troops in South Vietnam, and the enormous logistics train the North maintained for the benefit of its Viet Cong partners, complicated the development of American counterinsurgency strategy enormously. Throughout the war, American leaders had difficulty deciding whether the main enemy was the North Vietnamese Army (nva) or the Viet Cong (vc). In the initial phases of the war, the U.S. leadership focused more on the nva and therefore on using conventional American military capabilities to defeat the external threat. This was a convenient decision that allowed the U.S. to bring all its military power to bear: Troops fought the nva on the ground; aircraft and “swift boats” attempted to cut off North Vietnamese supply lines; bombers attacked targets within North Vietnam in an attempt to dissuade Ho Chi Minh from continuing the fight.

Efforts to conduct a real counterinsurgency within the South were generally overwhelmed by this focus on a more or less conventional struggle against North Vietnam. Thus critics then and since have complained that the Combined Action Platoons (caps) program pioneered by the Marines would have been much more successful if only it had been better resourced, for example. Such claims are plausible, but they generally ignore two defining factors of the South Vietnamese insurgency: the presence of sizable enemy units maneuvering throughout the country, and the illegitimacy of the South Vietnamese government.

U.S. involvement in the military struggle in Vietnam followed the assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem, apparently with President Kennedy’s knowledge and consent, and his replacement by a series of military rulers with no real basis for legitimacy. This development is easier to criticize than it would have been to correct. Kennedy and his advisors were quite right that Diem was neither sufficiently popular nor sufficiently talented to serve as a key to political success, but at the same time it is difficult to imagine any government replacing him following an assassination that would have been able to gain the support of the people rapidly. The political circumstances of this war were extremely unpropitious.

But the military circumstances were even worse. Not only were there vc units roving the countryside and taking over villages periodically, but nva regular formations also maintained a continual presence in the South throughout the period of American involvement. The famous Tet Offensive of 1968 was a military disaster for the Vietnamese communists, but it was nevertheless a large-scale conventional military attack that posed a major challenge to American forces before they were able to crush it. And the war ended, of course, when North Vietnam launched a massive conventional offensive that defeated the South Vietnamese army in conventional battles in 1975, seizing the country and subjugating it.

American forces in Vietnam certainly did face many of the problems common to insurgencies, including fighting for the “hearts and minds” of the populace, combating guerrillas who do not wear uniforms and who blend into the local population when not shooting, and so on. For many American soldiers, these were the standard problems of day-to-day existence, and there are no doubt many lessons to be drawn on this tactical level. But the defining events and movements of this war depended upon the presence of an inviolate sanctuary (no American president was ever willing to invade North Vietnam, and even the bombing was narrowly constrained in its targeting, if very heavy) and of large numbers of indigenous and external soldiers organized into military units of up to division size. This fact shaped the counterinsurgency problem and American strategy so profoundly that comparisons to Iraq today, in which neither factor is significant, are inappropriate.

Iraq

he situation in Iraq is completely different from Vietnam. The beginning of the conflict, the nature of the enemy, the enemy’s military capabilities, the nature of the current Iraqi government, and the legitimacy of that government are all so widely removed from the circumstances of Vietnam as to make meaningful comparisons almost impossible.

American involvement in Iraq followed the coalition’s invasion of that country in April 2003 and the destruction of a tyrannical regime. The elimination of that regime led to rejoicing on the streets and has had, according to polls, the approval of a great majority of the Iraqi people. Since the fall of Baghdad, coalition forces have faced a threefold enemy. Elements of the former regime continued to fight against the coalition for about six months after the end of major combat, until the capture of Saddam Hussein largely wound up that struggle. In early 2004, it became apparent that Islamic militant radicals such as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi had infiltrated Iraq and were establishing terrorist cells, some linked to al Qaeda, in order to drive the Americans out and establish a Taliban-style radical Muslim state. In the spring of that year, it also became apparent that a significant portion of the Arab Sunni minority in Iraq had not accepted its defeat and its removal from centuries of control over the country. Since then, the coalition has struggled with attacks on its own forces and on its Iraqi allies from these foes.

It is impossible to estimate the number of insurgents in Iraq, as it nearly always is in any insurgency. There is probably a “hard core” of dedicated, full-time fighters numbering perhaps several thousand. Beyond that, there is no way to know how many part-time fighters, potential fighters, and sympathizers are in the Iraqi population. Several things are certain about this enemy, however, that stand in stark contrast to the enemy the U.S. faced in Vietnam.

First, the enemy is almost exclusively Iraqi. There are certainly foreign fighters in Iraq, and many believe that those fighters make up the majority of the suicide bombers attacking coalition forces, Iraqi troops, and Iraqi civilians. Such attacks, however, number several hundred per year. That datum, combined with a number of other indications suggests strongly that there are very few foreign fighters in Iraq — perhaps a few hundred, perhaps a thousand or so. Whatever the importance of those fighters to the insurgency, and they are undeniably important, this situation is in no way comparable to one in which Hanoi kept tens of thousands of regular soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army in South Vietnam for years. In the case of Vietnam, there was a certain amount of sense to the belief that the problem really did come mainly from the North (although even in that case that belief was almost certainly overdrawn). To imagine that a few hundred foreign fighters are the primary challenge the coalition faces in Iraq is nonsense.

Second, the enemy in Iraq is incapable of conducting meaningful guerrilla warfare at this point. Guerrilla warfare implies the use of military or paramilitary forces to attack regular troops using “unconventional” techniques: raids, ambushes, etc. Most guerrillas use hit-and-run tactics because they know that they cannot stand up to regular troops in a conventional fight, but they generally operate in small organized units and seek to achieve military objectives, such as denying the enemy the use of certain roads, preventing the delivery of supplies to enemy troops, wiping out isolated enemy detachments, and even briefly seizing population centers to gather recruits and supplies of their own.

Iraq has seen very little guerrilla warfare during this fight, and virtually none since the retaking of Fallujah in November 2004. Since that time, Iraqi insurgents have generally operated in groups of two or three, not militarily significant guerrilla formations. (Only in a handful of safe havens allowed them by the coalition, such as Fallujah and Tall Afar, have the insurgents ever organized significant military forces. But even these forces have been unable to present serious military obstacles to determined U.S. efforts to clear them out.) They have largely stopped attacking coalition forces and are now focusing their efforts on terror attacks against Iraqi Army soldiers, police, and civilians. With few exceptions, these attacks have no military significance. They do not prevent the coalition from moving its forces at will throughout the country. They threaten the supplies of no American troops. They have not wiped out or even tried to wipe out isolated coalition units — and those units move around the country now in very small detachments upon which vc or nva troops would have fallen with glee.

It is true that the continual drumbeat of ied and vbied attacks, and the increasingly rare firefight as coalition forces move into positions that the insurgents hope to contest, have forced the coalition to adopt and maintain a certain force protection posture that affects its political and military operations. That “military” effect, however, is so far removed from the effect of day-to-day combat between soldiers and Marines on the one hand and vc and nva troops on the other as to bear no comparison. And that is to say nothing of the Tet Offensive or the final North Vietnamese offensive of 1975. The military capabilities of the Iraqi insurgents are simply not in the same league as those of the Vietnamese.

The political situation in Iraq is also very different. The U.S. began by removing an unpopular dictator and moved very rapidly to choose a new government. The coalition first ruled Iraq directly, as an occupying power, between April 2003 and June 2004, under the auspices of the Coalition Provisional Authority advised by an Iraqi Governing Council. The decision not to turn Iraqi sovereignty formally back over to some sort of Iraqi government immediately has received a certain amount of criticism, but it was almost certainly wise. It allowed the coalition to take certain steps both to secure the country and to establish and reestablish critical infrastructure and governing institutions without the inevitable price of entrammeling what would have seemed clearly to be a puppet government in those decisions.

On the other hand, the transfer of authority to the Interim Government of Ayad Allawi in June 2004 ended the formal occupation and created an Iraqi government with the obligation to mobilize its own resources, including public opinion, to keep the country together and to continue democratic progress. The elections of January 2005 were boycotted by the Sunni Arab community, a fact of no little importance. But even more important is the fact that they returned a government that a large majority of Iraqis (the Shi’a and Kurds) felt was legitimate. The U.S. was never able to find any government in Saigon that could command anything like such support among its own people.

The political (and military) problems in Iraq are now, therefore, largely confined to a single minority community — the Sunni Arabs. The challenge that the Iraqi government and the coalition face now is convincing that community that it must abandon violence and participate in a political process even though it is certain never to regain the degree of control over Iraq’s affairs that it has enjoyed for centuries. This, the most critical problem in Iraq today, has no parallel in Vietnam.

Differences in kind

number of other vital differences separate the Iraqi resistance from America’s enemies in Vietnam, and also separate the U.S. armed forces today from those that fought in Southeast Asia. These differences help to explain in part why the coalition has so far been so much more successful in Iraq than it ever was in Vietnam, although they will not be sufficient by themselves to lead to victory.

The various enemies the coalition faces in Iraq differ from the vc and the nva in three critical ways. First, they have a variety of more or less well developed ideologies, but none that is remotely as appealing to the American or international public as communism and anti-colonialism was. Second, although they do receive support from outside Iraq, that support pales to insignificance in comparison to the assistance the Soviet Union provided to North Vietnam, and North Vietnam to the vc. Third, they have infinitely less meaningful military experience than either the vc or the nva, and much of that experience was bad.

The Iraqi insurgents have primarily two ideologies to offer. One is the al Qaeda vision of radical militant Islamism and permanent jihad. The other is a sort of defiant nationalism based on the premise that the minority Sunni Arabs should dominant the Shi’a and Kurds they have brutally oppressed for decades and, indeed, centuries. The appeal of these ideologies within the Sunni Arab community is clearly mixed. That community’s performance in both the January elections and the recent referendum shows that by no means all of its members adhere to one or the other of these ideologies or, if they do, that they do not all agree with the specific insurgent strategies being pursued. The appeal of those ideologies within the Shi’a and Kurdish communities, however, is clearly infinitely lower, and the number of Americans likely to be attracted by them is vanishingly small. We are unlikely to see at any time in this war a famous actress staring bloodthirstily through the sites of an Iraqi rebel’s rpg, or any of the other manifestations of sympathy to the Vietnamese cause. The cause of these insurgents is entirely antipathetic to the overwhelming majority of Americans, even aside from the fact that the Jihadists’ message is that America must be destroyed.

Much has been made of the support the Iraqi insurgents receive from abroad, particularly from the international Jihadist movement, and the analogy of the Ho Chi Minh trail has led to enormous scrutiny of coalition efforts to seal Iraq’s borders. We have already seen that the degree of foreign fighter infiltration into Iraq is probably two orders of magnitude below the degree of North Vietnamese infiltration of the South. We should also note that the logistical support available to the Iraqi insurgents from abroad is as nothing compared with the support the Soviets provided the Vietnamese. North Vietnamese pilots, we should remember, flew MiGs with great skill against their American adversaries and imposed fearful losses at times on their U.S. attackers. They used surface-to-air missiles delivered straight from Soviet bloc countries to down U.S. helicopters and aircraft. They benefited from numerous Soviet advisors and from intelligence provided by Soviet satellites and intelligence trawlers. The list goes on.

America’s adversaries in Iraq receive, in comparison, almost nothing from outside. The weapons and ammunition they use are what they could liberate from Saddam Hussein’s warehouses before coalition troops took control of them, and what they can still steal from those sources or buy on the international arms market. They have no aircraft, no heavy vehicles, no sophisticated air defense networks. They have no professional military advisors, and the resources of the intelligence services of no great power. The international movement of which they are a part is apparently so weak that Osama bin Laden’s deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, recently wrote to the leader of al Qaeda in Iraq, Zarqawi, asking him to send money to Zawahiri!

The skills of the insurgent fighters in Iraq are also, finally, much below those of the vc and nva troops the U.S. fought in Vietnam. As noted, the Vietnamese insurgency raged for 20 years before the U.S. became directly involved. The vc and nva troops we fought included veterans of that struggle and were led by the men who had defeated the French already. They were seasoned soldiers and tested leaders who had developed their skills fighting the same fight against a similar sort of enemy long before we ever arrived. They were a formidable military foe.

The Iraqi insurgents have no such experience. Although Saddam Hussein forced all young Iraqi males to serve in his army, and thereby in theory created a pool of trained soldiers, that army was a truly terrible fighting force. Morale was low; training, especially for the last decade before the war, was seriously curtailed and of poor quality; troops had virtually no combat experience. The only meaningful experience even the senior leaders had, moreover, was the experience of losing to the Americans twice in a total of eight weeks of combat, and of fighting the Iranians to a draw in an ugly conventional war. They were anything but seasoned veterans of insurgency warfare.

The foreign fighters bring a certain amount of experience in such wars to the insurgents, it is true, and they have introduced a number of techniques of international jihad into the struggle. But early fears that they would import the skills they used to defeat the Soviets in Afghanistan wholesale into Iraq proved unfounded. Most of these foreign infiltrators are young. They are in Iraq because they choose to be, not because any professional organization selected and trained them. Their relationship with the Sunni Arab insurgents is unclear but is obviously, at times, strained. And their numbers are tiny. Together with the mass of the Sunni Arab insurgents, they comprise a foe that, militarily speaking, is far from fearsome.

The American military, however, is infinitely better trained, equipped, and motivated today than it was at any point in the Vietnam War. The advantages of a volunteer over a conscript army in such wars are incalculable. The technology of the current American military, although not developed for counterinsurgency struggles, has proven to be almost as valuable in such fights as it was in conventional war. And the American soldiers of today are so much more experienced in many of the sorts of tasks they face than were the conscripts of 1965 that there is no comparison between the two.

The U.S. Army and Marine Corps today are the most highly trained troops in the world. Units that deploy to Iraq have typically been through one of the superb training centers established in the 1980s, and have trained extensively at the individual and sub-unit level for months prior to their deployment. The individuals in those units have years of experience in uniform. They chose a military career willingly and they have chosen to remain in that career even as the military has engaged in extensive combat over the past four years. As a result, the morale of the soldiers in Iraq is very high, as shown by the amazing percentage of reenlistments among deployed units. The military, especially the ground forces, has been seriously stretched by deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan, but those problems have not yet filtered down to the individual soldiers and units doing the fighting enough to reduce their effectiveness.

One of the most important manifestations of this professionalism and expertise is in the discretion with which U.S. ground troops use force in Iraq. The days of “destroying the village to save it,” of indiscriminate bombing or artillery shelling, even of indiscriminate small-arms fire are largely over. The experienced and highly trained soldiers of the volunteer military can remain cooler under fire and are therefore much better able to distinguish between friend and foe, and between enemies and innocent civilians, than the conscripts of the Vietnam era.

The professionalism of these soldiers has also minimized the ability of the insurgents to harm U.S. servicepeople. Experienced and well-trained soldiers make fewer mistakes and do fewer foolish things that provide opportunities to the enemy. Not only are our present foes less skilled than their Vietnamese predecessors, but they would have to be significantly more skilled to harm our better trained and better motivated volunteer soldiers in the way the Vietnamese did.

America’s soldiers, what is more, have an enormous amount of experience today in many of the difficult tasks they have to accomplish in this type of war. The Army has had soldiers in Bosnia and then Kosovo and Afghanistan engaged in peacekeeping, police operations, reconstruction activities, and humanitarian assistance for a decade. U.S. soldiers deployed to Iraq knew how to rebuild damaged water or sewage systems, how to provide medical assistance to the local population, how to maintain order in the face of threatening crowds without generating mass casualties, how to patrol dangerous streets. Americans in Vietnam had no such experience — the last major war had ended more than a decade before and had been entirely conventional. The “peacekeeping” Army of the 1990s had already perfected many of the techniques that would prove essential for the counterinsurgency Army of today.

The technological improvement of the U.S. military between 1975 and 2005 has also revolutionized counterinsurgency warfare almost as much as it did conventional war. Precision-guided munitions now allow the use of U.S. airpower in support of discrete tactical operations without generating excessive collateral damage. The near-invulnerability of the military’s armored vehicles has also proven invaluable: Repeatedly during the battles of Fallujah and elsewhere, the arrival of American tanks or Bradleys meant that the insurgents’ day was done. Perhaps the most remarkable difference, however, comes from a seemingly trivial piece of equipment: Night-vision goggles and infrared sensors mean that coalition forces, not the insurgents, now own the night. The vc and the nva used to terrorize American infantry when darkness fell. Today it is the other way around, and the insurgents hardly try to operate at night at all. All of these technological developments, and many more, have helped contribute to the rapid collapse of meaningful guerrilla activity in Iraq and make it unlikely that such activity will develop again as long as American forces remain there in significant numbers.

The nature of the terrain, finally, makes Iraq as suitable an arena for counterinsurgency warfare as the U.S. could ever ask for. The desert and farmland that make up most of the country provide little meaningful cover. The urban centers are more daunting, but they allow the use of most American vehicles most of the time, and vehicles have long been the backbone of U.S. ground forces. The Iraqi insurgency is, in fact, a vehicle war on both sides. The insurgents ride taxis or commandeered cars to the battle and escape contact the same way. Zarqawi and other insurgent leaders drive many miles every day to escape the coalition and Iraqi forces constantly chasing them. The prevalence of vehicle-borne ieds is testimony to the centrality of vehicles for all combatants in this struggle, and that centrality gives the advantage, in the end, to the coalition, whose vehicles are better protected and better armed than those of the enemy. Vietnam, of course, was a light-infantryman’s war, and the most dramatic technological innovation of that struggle, the use of helicopters to transport masses of soldiers around, ended with the deployment of light infantrymen who walked from place to place. The nature of the struggle in Iraq suits the U.S. much better on the whole.

The purpose of this exposition is not to argue that the challenges facing the coalition in Iraq are small or that success will come easily. On the contrary, the challenges are great, and failure is quite possible. But the challenges Iraq poses are of quite a different order from those posed by the conflict in Vietnam, and we must eliminate the false comparisons that can too easily cloud our thinking as we ponder our strategy today.

“Lessons” of Vietnam

Are there, then, no lessons that we can learn from Vietnam to improve our strategy in Iraq? Of course, there are. But many of them have already been implemented, and we must be as concerned about the danger of applying false lessons as about the risk of not applying valid ones. The importance of minimizing civilian casualties and collateral damage emerges clearly from Vietnam, and centcom has taken that lesson very much to heart. It is doubtful that any military organization could do better in this regard than the coalition has in Iraq, despite a certain number of mistakes. The importance of integrating planning for humanitarian assistance and reconstruction efforts into military operations is also clear from Vietnam, and here again centcom has done an outstanding job by comparison with any other such conflict. We have already considered the numerous political lessons the Bush administration clearly learned from that failure three decades ago, and that it has applied intelligently and with an astonishing degree of success in Iraq. Much of what has gone right in Iraq is the result of reactions of one sort or another to the experience of Vietnam.

It is unlikely, however, that plumbing Vietnam for additional examples, for strategies to defeat the insurgents, or for other insights into this very different conflict will be helpful. The military problem in Vietnam was critical and overwhelming, and the U.S. never solved it (there is no need to enter into the debate about the degree to which political constraints prevented this solution). The political difficulties of the situation almost inevitably took a back seat to the crisis resulting from the clash of arms on the battlefield. Without venturing into another great Vietnam debate, it is enough to observe that whatever the value and wisdom of the caps program or other similar efforts, and whatever the unwisdom of General Westmoreland’s failure to support those program adequately, it would have been infinitely more difficult for him to do so than it has proven for General Abizaid to prioritize reconstruction and humanitarian assistance, say. There are today nothing like the continuous serious guerrilla attacks and firefights that require the massive use of airpower to enable American units to survive at all to distract attention from winning hearts and minds, as there were in Vietnam. centcom’s very focus on those issues is testimony to the relative insignificance of the overt military challenge the coalition faces.

The focus on Vietnam and the general confusion between insurgency (any sort of political or military struggle against an established government) and guerrilla warfare (the use of particular kinds of military forces in unconventional warfare) is even leading us down the wrong road militarily. Strategies like the “oil spot” approach recently proposed, in which coalition forces would concentrate on pacifying a limited number of areas and then spreading their control outward, might or might not have been appropriate for Vietnam, but they are inappropriate for Iraq. Whatever the effect of such a strategy in Vietnam, in Iraq it would be a step backward, since most of the country already is pacified, and abandoning parts of, say, the Sunni Triangle to concentrate on other parts would only provide the insurgents guaranteed safe havens they do not now have.

The fact is that, militarily, the situation in Iraq is at a level below that of guerrilla war. The enemy is engaged in a widespread terrorist campaign much more similar to the Intifadah or the ira’s or eta’s attacks, if more concentrated and destructive. The coalition has already drawn some lessons from those struggles, in fact, as recent anti-terrorist operations in Iraq have focused on finding and killing or capturing the bomb makers rather than the bomb placers — a lesson centcom drew from the British experience in Northern Ireland. It may be that the more careful scrutiny of those conflicts will be more fruitful than the continuing study of Vietnam or other guerrilla wars.

Any single historical example, however, will suffer from sharp limits in its power to explain, still less prescribe solutions for, the current conflict. All insurgencies are distinct from one another, of course, but Iraq is particularly unusual in the set of challenges it poses and in the history behind the struggle. Historical examples are most likely to be useful in understanding it when considered in depth, comparatively with one another, and with the clear knowledge of their differences from the current troubles. History does not, in the end, provide “lessons” to be learned. At its best, it provides guidelines to help think concretely and creatively about current and likely future problems. We’ve gotten what we are going to get out of the Vietnam example, or any other single example, already. It is time to move on.

The real reason that the Vietnam example remains so prominently in many people’s minds, of course, is that the U.S. lost that war. By comparing Iraq to Vietnam, many people are expressing the fear that because America lost one and because of certain superficial similarities, the U.S. is on the road to losing the other. This “lesson” of history is the least valid of all. America may fail in Iraq, but, if so, it will not be because of any similarity to Vietnam. It is much more likely, moreover, that if the Bush administration pursues a sound strategy in this struggle, the U.S. — and the Iraqi people — will win.

Frederick W. Kagan is resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

Copyright © 2005 The Hoover Institution

Monday, December 12, 2005

Vietnam ≠ Iraq

Laugh Out-Loud Funny

I cachinnated when I read this takeoff on the Bushies' ludicrous attempts to buy good press in Iraq via the DC PR firm, The Lincoln Group. Dumb sumbitches (Bushies) thought they could skate this one through. If this is (fair & balanced) stupidity, so be it.

[x The Hartford Courant]

The upbeat beat in Iraq

By Jim Shea

To: The Lincoln Group

Subject: Writing opportunity

Dear Sir or Madam:

Regarding The Lincoln Group's $6 million contract with the Pentagon to handle its public relations work in Iraq, I am inquiring as to whether you are looking for any more writers to produce positive stories for planting in newspapers there.

I have many years experience in the journalism business and am currently working for a mainstream American newspaper - the last time I checked.

I understand Lincoln has been under criticism of late for paying local Iraqi papers to run articles with a pro-American slant, but for the life of me I don't understand what the fuss is. I mean, the freedom to mislead the public through the media is what democracy is all about.

Here are a few ideas I have for stories that I am sure would go a long way toward creating a more upbeat view of how things are steadily turning around in Iraq:

Baghdad to get NBA team

National Basketball Association Commissioner David Stern announced today that Baghdad has been awarded an NBA franchise. The team will begin play in the 2006-07 season and be called the Insurgents.

Pesky car bomb problem solved

Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld has unveiled an ambitious drive to ban motor vehicles in Iraq and replace them with Segways. The Pentagon plans to set up Segway dealerships throughout the country, where salesmen will be offering the nifty electric scooters at ''unbelievably low prices'' and accepting trades on any vehicle that can be ''driven, dragged or pushed'' onto the lot.

Housing sector remains hot

Buoyed by new construction, the Iraqi housing industry had another strong quarter. Housing starts were up 20 percent, while housing demolitions were running at 30 percent, meaning a building slowdown in the immediate future is unlikely. Usury rates remained unchanged.

Prescription drug plan is announced

Iraqi seniors will soon be able to get their prescription drugs at a substantial savings thanks to a plan patterned after the wildly successful Medicare program. The new benefit is scheduled to go into effect as soon as a drugstore opens and will be called Iraqi-Care. For more information, call 1-800-Geo-Bush.

Mahdi Army Choir presents holiday program

The Mahdi Army Choir, under the direction of militant cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, will roll out a traditional holiday show this weekend tinged with just a bit of Iraqi flair. The musical offerings will include such favorites as: "I Saw Mommy Kissing Chemical Ali," "Adeste Infidels," and "Grandma Got Run Over by a Hummer."

Jim Shea is a columnist for The Hartford Courant.

Copyright © 2005 The Hartford Courant

Oh, Really?

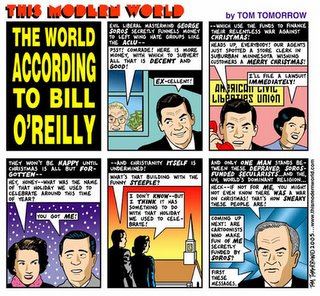

The poster boy for conspiratorial fantasies is Bill O'Reilly on Fox Television's (Unfair & Unbalanced) "The O'Reilly Factor." Personally, I enjoy Stephen Colbert's nightly send-up of O'Reilly on Comedy Central's "Colbert Report." "The Modern World" by Tom Tomorrow in today's Salon takes O'Reilly's wackiness over the edge where it belongs: the loony bin. On top of that, I am a proud, card-carrying member of the ACLU. Take that, Oh Really! If this is (fair & balanced) secularism, so be it.

Copyright © 2005 Salon