Frank Rich is the leadoff Op-Ed hitter in the NY Fishwrap's Sunday lineup. JFK's ghost is walking our political landscape. Frank Rich, between the lines, is endorsing Obama. If this is (fair & balanced) punditry, so be it.

[x NY Fishwrap]

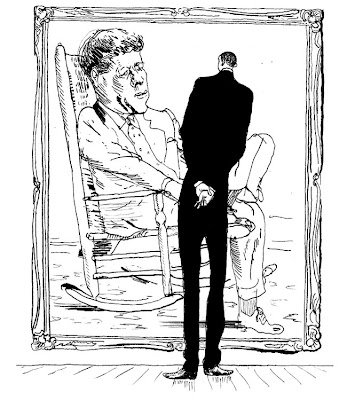

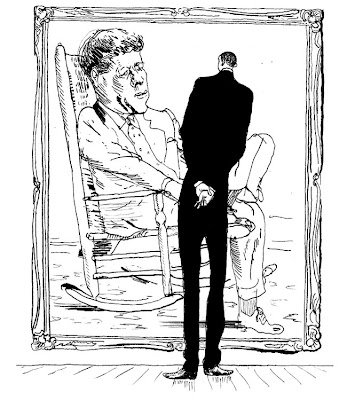

Click on image to enlarge/Copyright © 2008 Barry BlittAsk Not What J.F.K. Can Do for Obama

By Frank Rich

Before John F. Kennedy was a president, a legend, a myth and a poltergeist stalking America’s 2008 campaign, he was an upstart contender seen as a risky bet for the Democratic nomination in 1960.

Kennedy was judged “an ambitious but superficial playboy” by his liberal peers, according to his biographer Robert Dallek. “He never said a word of importance in the Senate, and he never did a thing,” in the authoritative estimation of the Senate’s master, Lyndon Johnson. Adlai Stevenson didn’t much like Kennedy, and neither did Harry Truman, who instead supported Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri.

J. F. K. had few policy prescriptions beyond Democratic boilerplate (a higher minimum wage, “comprehensive housing legislation”). As his speechwriter Richard Goodwin recalled in his riveting 1988 memoir “Remembering America,” Kennedy’s main task was to prove his political viability. He had to persuade his party that he was not a wealthy dilettante and not “too young, too inexperienced and, above all, too Catholic” to be president.

How did the fairy-tale prince from Camelot vanquish a field of heavyweights led by the longtime liberal warrior Hubert Humphrey? It wasn’t ideas. It certainly wasn’t experience. It wasn’t even the charisma that Kennedy would show off in that fall’s televised duels with Richard Nixon.

Looking back almost 30 years later, Mr. Goodwin summed it up this way: “He had to touch the secret fears and ambivalent longings of the American heart, divine and speak to the desires of a swiftly changing nation — his message grounded on his own intuition of some vague and spreading desire for national renewal.”

In other words, Kennedy needed two things. He needed poetry, and he needed a country with some desire, however vague, for change.

Mr. Goodwin and his fellow speechwriter Ted Sorensen helped with the poetry. Still, the placid America of 1960 was not obviously in the market for change. The outgoing president, Ike, was the most popular incumbent since F. D. R. The suburban boom was as glossy as it is now depicted in the television show “Mad Men.” The Red Panic of the McCarthy years was in temporary remission.

But Kennedy’s intuition was right. America’s boundless self-confidence was being rattled by (as yet) low-grade fevers: the surprise Soviet technological triumph of Sputnik; anti-American riots in even friendly non-Communist countries; the arrest of Martin Luther King Jr. at an all-white restaurant in Atlanta; the inexorable national shift from manufacturing to white-collar jobs. Kennedy bet his campaign on, as he put it, “the single assumption that the American people are uneasy at the present drift in our national course” and “that they have the will and strength to start the United States moving again.”

For all the Barack Obama-J. F. K. comparisons, whether legitimate or over-the-top, what has often been forgotten is that Mr. Obama’s weaknesses resemble Kennedy’s at least as much as his strengths. But to compensate for those shortcomings, he gets an extra benefit that J. F. K. lacked in 1960. There’s nothing vague about the public’s desire for national renewal in 2008, with a reviled incumbent in the White House and only 19 percent of the population finding the country on the right track, according to the last Wall Street Journal-NBC News poll. America is screaming for change.

Either of the two Democratic contenders will swing the pendulum. Their marginal policy differences notwithstanding, they are both orthodox liberals. As the party’s voters in 22 states step forward on Tuesday, the overriding question they face, as defined by both contenders, is this: Which brand of change is more likely, in Kennedy’s phrase, to get America moving again?

Lost in the hoopla over the Teddy and Caroline Kennedy show last week was the parallel endorsement of Hillary Clinton by three of Robert Kennedy’s children. In a Los Angeles Times op-ed article, they answered this paramount question as many Clinton supporters do (and as many John Edwards supporters also did). The “loftiest poetry” won’t solve America’s crises, they wrote. Change can be achieved only by a president “willing to engage in a fistfight.”

That both Clintons are capable of fistfighting is beyond doubt, at least on their own behalf in a campaign. But Mrs. Clinton isn’t always a fistfighter when governing. There’s a reason why Robert Kennedy’s children buried the Iraq war in a single clause (and never used the word Iraq) deep in their endorsement. They know that their uncle Teddy, unlike Mrs. Clinton, raised his fists to lead the Senate fight against the Iraq misadventure at the start. They know too that less than six months after “Mission Accomplished,” Senator Kennedy called the war “a fraud” and voted against pouring more money into it. Senator Clinton raised a hand, not a fist, to vote aye.

In what she advertises as 35 years of fighting for Americans, Mrs. Clinton can point to some battles won. But many of them were political campaigns for Bill Clinton: seven even before his 1992 presidential run. The fistfighting required if she is president may also often be political. As Mrs. Clinton herself says, she has been in marathon combat against the Republican attack machine. Its antipathy will be increased exponentially by the co-president who would return to the White House with her on Day One.

It’s legitimate to wonder whether sweeping policy change can be accomplished on that polarized a battlefield. A Clinton presidency may end up a Democratic mirror image of Karl Rove’s truculent style of G.O.P. governance: a 50 percent plus 1 majority. Seven years on, that formula has accomplished little for the country beyond extending and compounding the mistake of invading Iraq. As was illustrated by the long catalog of unfinished business in President Bush’s final State of the Union address, this has not been a presidency that, as Mrs. Clinton said of L. B. J.’s, got things done.

The rap on Mr. Obama remains that he preaches the audacity of Kumbaya. He is all lofty poetry and no action, so obsessed with transcending partisanship that he can be easily rolled. Implicit in this criticism is a false choice — that voters have to choose between his pretty words on one hand and Mrs. Clinton’s combative, wonky incrementalism on the other.

There’s a third possibility, of course: A poetically gifted president might be able to bring about change without relying on fistfighting as his primary modus operandi. Mr. Obama argues that if he can bring some Republicans along, he can achieve changes larger than the microinitiatives that have been a hallmark of Clintonism. He also suggests, in his most explicit policy invocation of J. F. K., that he can enlist the young en masse in a push for change by ramping up national service programs like AmeriCorps and the Peace Corps.

His critics argue back that he is a naïve wuss who will give away the store. They have mocked him for offering to hold health-care negotiations so transparent (and presumably feckless) that they can be broadcast on C-Span. Obama supporters point out that Mrs. Clinton’s behind-closed-doors 1993 health-care task force was a fiasco.

A better argument might be that transparency could help smoke out the special-interest players hiding in Washington’s crevices. You’d never know from Mrs. Clinton’s criticisms of subprime lenders that one of the most notorious, Countrywide, was a client as recently as October of Burson-Marsteller, the public relations giant where her chief strategist, Mark Penn, is the sitting chief executive. Other high-level operatives in her campaign belong to Dewey Square Group, an outfit that just last year provided lobbying services for Countrywide.

The question about Mr. Obama, of course, is whether he is tough enough to stand up to those in Washington who oppose real reform, whether Republicans or special-interest advocates like, say, Mr. Penn. The jury is certainly out, though Mr. Obama has now started to toughen his critique of the Clintons without sounding whiny. By framing that debate as a choice between the future and the past, he is revisiting the J. F. K. playbook against Ike.

What we also know is that, unlike Mrs. Clinton, Mr. Obama is not hesitant to take on John McCain. He has twice triggered the McCain temper, in spats over ethics reform in 2006 and Mr. McCain’s Baghdad market photo-op last year. In Thursday’s debate, Mr. Obama led an attack on Mr. McCain twice before Mrs. Clinton followed with a wan echo. When Bill Clinton promised that his wife and Mr. McCain’s friendship would ensure a “civilized” campaign, he may have been revealing more than he intended about the perils for Democrats in that matchup.

As Tuesday’s vote looms, all that’s certain is that today’s pollsters and pundits have so far gotten almost everything wrong. Mr. McCain’s campaign had been declared dead. Mrs. Clinton has gone from invincible to near-death to near-invincible again. Mr. Obama was at first not black enough to sweep black votes and then too black to get a sizable white vote in South Carolina.

Richard Goodwin knew in 1960 that all it took was “a single significant failure” by Kennedy or “an act of political daring” by his opponents for his man to lose — especially in the general election, where he faced the vastly more experienced Nixon, the designated heir of a popular president. That’s as good a snapshot as any of where we are right now, while we wait for the voters to decide if they will take what Mrs. Clinton correctly describes as a “leap of faith” and follow another upstart on to a new frontier.

[

New York Times columnist Frank Rich's new book is

The Greatest Story Ever Sold: The Decline and Fall of Truth from 9/11 to Katrina. Rich has been with the

Times since 1980, when he was named chief theater critic.

With reviews that could be devastating, Rich earned the nickname "The Butcher of Broadway." In 1994, Rich became an op-ed columnist for the paper, turning his focus to politics and culture.

Slate recently re-dubbed him "The Butcher of the Beltway."]

Copyright © 2008 The New York Times Company

Get an RSS (Really Simple Syndication) Reader at no cost from Google. Another free Reader is available at RSS Reader.