The Rumster is a war criminal. There is no sugar-coat that will obscure that fact. When a general ends his career with a call for the firing of the Secretary of Defense, it is no laughing matter. All of The Rumster's smirks and wisecracks do not detract from the point that The Rumster must go. By implication, The Rumster's commander-in-chief must go as well. If this is (fair & balanced) verisimilitude, so be it.

[x Wall Street Fishwrap]

The Two-Star Rebel

By Greg Jaffe

For Gen. John Batiste, a tour in Iraq turned a loyal soldier into Rumsfeld's most unexpected critic.

Six days after he called for Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld to leave his post, retired Maj. Gen. John Batiste faced a crushing moment of doubt.

Earlier that morning, Mr. Rumsfeld had brushed off Gen. Batiste and other critics as inflexible bureaucrats, uncomfortable with change. A few hours later, President Bush vowed to stand by his secretary.

Now CNN's Paula Zahn was grilling Gen. Batiste: "So, do you plan to continue with these kinds of attacks ... when the president has made it clear he's not budging?"

"I have yet to determine if I will do that or not," Gen. Batiste said.

Afterward, the 53-year-old officer retreated to a deserted parking garage outside the television station. For 30 minutes, he paced up and down, he says, literally shaking. Military officers, like Gen. Batiste, are constantly reminded that their role is to advise civilian leaders and execute their orders -- even if they disagree with them.

Now he was stepping way out of that culture. Gen. Batiste and his wife, the children of career military officers, had spent their entire lives in the Army. He fought in the first Gulf War, led a brigade into Bosnia, and in 2004 commanded 22,000 troops in Iraq, losing more than 150 soldiers.

"I was shocked at where I was," he says. "I had spent the last 31 years of my life defending our great Constitution." Over the course of the war in Iraq he says he saw troop shortages that allowed a deadly insurgency to take root, felt politics were put ahead of hard-won military lessons and was haunted by the regretful words of a top general in Vietnam.

The war in Iraq should have been a decisive victory for the U.S., Gen. Batiste told himself, as he paced in the parking garage. He blamed Mr. Rumsfeld for his "contemptuous attitude" and his "refusal to take sound military advice." As he got into his car to drive home, he recalls thinking: "If I don't speak out, who the hell else will?"

Since March, seven retired generals have called for Mr. Rumsfeld's resignation. Some critics argue that the dissenters, a fraction of the hundreds of generals who have retired in the last decade, have axes to grind or have no first-hand experience working with the secretary. Three were passed over for promotions or forced to retire. Two left the military before the Bush administration took office. (See a gallery1 of other former military officers' criticism of Rumsfeld.)

Gen. Batiste stands out among the generals who have called for Mr. Rumsfeld to resign because he is the only one who served in a high position in the Pentagon and commanded troops in Iraq. He turned down a promotion and resigned last fall. He then spent the next seven months trying to decide whether to speak out in public, weighing a strong sense of duty and respect for his chain of command against a feeling that he owed it to his soldiers and their families to speak out.

Among the generals who have spoken out, "the only one that really shocked everyone was Batiste," says Don Snider, a professor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Mr. Rumsfeld has suggested that the criticism of him by the retired generals is a byproduct of the sweeping reforms he brought to the Pentagon and the Bush administration's bold efforts to win the global war on terror by spreading freedom in the Middle East. "There's a lot of change going on; it's challenging for people, it's difficult for people," he told reporters recently.

For many senior military officers, today's debate over whether to speak out has its roots in the Vietnam War. All of today's senior generals either fought in the lost war or joined a military struggling to recover from it. "Their memory of Vietnam is that the military was abandoned by the American people and betrayed by the civilian leadership. It is hardwired into them never to let that happen again," says Andrew Bacevich, a professor of International Relations at Boston University and a retired Army colonel.

Gen. Batiste grew up on military bases, in the U.S., Europe and Iran. He followed his father, who fought in World War II, Korea and Vietnam, into the military. One of his most powerful memories is of his father, then a colonel, returning from Vietnam in the late 1960s. "I remember picking him up with my mom and sister at Dulles Airport. He came home so unceremoniously," Gen. Batiste says. "The people in the airport could not have cared less."

Gen. Batiste speaks in the short, crisp sentences of a person accustomed to giving orders. He graduated from West Point in 1974 and joined an Army damaged by the Vietnam War. As he walked into his battalion headquarters building for his first day at Fort Hood, Texas, he recalls medics carrying out the corpse of a soldier who had overdosed on heroin. "I thought to myself, 'Holy s-t, what have we done to this Army?' " he says.

In 1977, he married his battalion commander's daughter. He rose quickly through the ranks, serving as the military aide to Army Gen. Barry R. McCaffrey at Fort Benning, Ga. "I wrote on his officer evaluation that I wished he could have replaced me and I could have worked for him. That's how highly I thought of him," says Gen. McCaffrey, who retired in the 1990s.

Gen. Batiste fought in the first Gulf War, a quick victory that for many officers ratified their work to rebuild the Army after Vietnam. In 1995, he led one of the first 3,000-soldier brigades into Bosnia to protect embattled Muslims from the Serbs. The infantry officer figured out how to use his brigade's 70-ton tanks and attack helicopters to intimidate the enemies without firing a shot.

And Gen. Batiste learned how to turn potential adversaries into allies. Eight months into the mission, he was summoned to a hotel to meet with hostile Serbian officers and ended up in the middle of a rollicking wedding party, with a band and snaking conga line. He collected $100 from fellow officers and presented it as a wedding gift. The excited bride and groom both kissed his cheeks three times.

In 2001, Mr. Rumsfeld and Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz arrived at the Pentagon with a mandate from President Bush to transform the military into a lighter, faster force. Mr. Wolfowitz tapped Gen. Batiste, who had been recommended by his superiors, to become his senior military assistant.

Mr. Rumsfeld and Mr. Wolfowitz kicked off their tenure with a massive review of military spending. To ensure that the generals and Congress didn't organize to block change, Mr. Rumsfeld insisted that much of the review initially be conducted in secret. As Mr. Wolfowitz's aide, Gen. Batiste had access to some of the high-level discussions.

Initial plans called for shrinking the Army by as much as 20%, to pay for high-tech airplanes, space and missile defense systems. In discussions with Mr. Wolfowitz, Gen. Batiste argued the virtues of a big Army, drawing on his Bosnia experience.

Some on Mr. Wolfowitz's staff say Gen. Batiste often offered a parochial Army view. He touted the Crusader artillery cannon, which was too heavy to move by plane and didn't mesh with President Bush's vision of light, agile forces. Studies dating to the Clinton administration branded the cannon unnecessary. Mr. Rumsfeld eventually spiked it.

The general says he forged a close relationship with Mr. Wolfowitz. "He is a brilliant, dedicated hard-working man," Gen. Batiste says. "I didn't always agree with him, but he listened. He was a fair man." Mr. Wolfowitz declined to comment for this article.

Gen. Batiste didn't feel the same way about Mr. Rumsfeld, who served as a Navy pilot from 1954 to 1957. Mr. Rumsfeld's plan to cut the Army by 20%, before 9/11, reflected a belief that new technology made it possible to win wars with smaller ground formations. "He came in with a lot of ideas about warfare that I thought were just bankrupt," Gen. Batiste says.

Gen. Batiste left the Pentagon in July 2002, after being promoted to command the 1st Infantry Division, one of the Army's 10 active-duty combat divisions. Half of his division was deployed in Kosovo. The rest of the Germany-based unit began preparing for war in Iraq.

Before the start of the war, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Eric Shinseki suggested that it would take several hundred thousand troops to stabilize Iraq. Both Mr. Rumsfeld and Mr. Wolfowitz publicly said that was wrong. Like many Army officers, Gen. Batiste was deeply upset by their public rebuke. "I won't ever forget the treatment of Gen. Shinseki," Gen. Batiste says.

But he kept his reservations about the war plan to himself. "You don't know what you don't know until you are there on the ground," Gen. Batiste says. In January 2004, after a personal sendoff from Mr. Wolfowitz, his division deployed to Iraq. Gen. Batiste oversaw a territory about the size of West Virginia in the heart of the Sunni Triangle.

Once in Iraq, he believed some of his reservations were justified. Like most units in Iraq at the time, the 1st Infantry Division's humvees lacked armor. His soldiers contracted with Iraqis to weld whatever metal they could find to the sides of their humvees.

He also felt the unit didn't have enough reconstruction funds. When Mr. Wolfowitz came to visit in June 2004, Gen. Batiste said that his division had spent $41 million in three months on rebuilding. It had $23 million left for the remaining six months of the year. That wasn't enough, he says, to repair infrastructure destroyed by decades of misrule and sanctions, such as sewer, electrical or health-care systems. In addition, reconstruction funds put unemployed Iraqi men, who offered a potential recruiting pool for the enemy, on the U.S. payroll.

Over the course of the year-long tour, Gen. Batiste says he had to deal regularly with troop shortages. On three occasions, he was ordered to send soldiers to help other U.S. units in the cities of Najaf and Fallujah to put down revolts. Typically, the Army holds a couple of units in reserve to deal with unforeseen flare-ups. But the desire to keep the force as lean as possible meant there were no extra troops in Iraq.

Each time his soldiers left their area, attacks, intimidation and roadside bombs spiked, Gen. Batiste says. "It was like a sucking chest wound," he says. Relationships that soldiers had painstakingly built with local sheiks -- who had been persuaded to cooperate with U.S. forces at great risk to themselves and their families -- were lost when the soldiers were sent elsewhere, he says.

Gen. Batiste told Mr. Wolfowitz about this problem during the June 2004 visit, saying increased unrest in his sector was the "direct result of the boots-on-the-ground decrease." But he told Mr. Wolfowitz he believed his soldiers were making progress.

Gen. Batiste says he also relayed his concerns to his military bosses in Baghdad. "I always spoke out within my chain of command. I spoke my mind freely and forcefully," he says. His immediate commanders, Lt. Gen Thomas Metz and Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, didn't respond to requests for comment. His commanders were sympathetic, Gen. Batiste says, but he doesn't know whether his concerns were relayed to the Pentagon.

Just weeks before his troops left Iraq, the general had an opportunity to confront Mr. Rumsfeld publicly. The secretary, who was making a 2004 Christmas tour through Iraq, came to meet with him and take questions from his troops.

Gen. Batiste introduced Mr. Rumsfeld to his soldiers as a "man with the courage and conviction to win the war on terrorism." The general says he was disillusioned with Mr. Rumsfeld's leadership at the time, but felt he needed to pump up his soldiers who were in the final days of a grueling, bloody deployment.

After the speech, Mr. Rumsfeld, accompanied by reporters, met with Gen. Batiste in his plywood office, in the corner of one of Saddam Hussein's unfinished marble palaces. Mr. Rumsfeld asked the general whether he had been given everything he needed, Gen. Batiste recalls. Not wanting to discuss problems in front of the press, he says he deflected the question, by talking about his efforts to train Iraqi security forces.

The defense secretary then turned to Gen. Batiste's boss, Gen. Metz and asked: "What has Batiste told you he needs that he has not received?" according to a Dec. 26, 2004, account of the meeting by the Associated Press. Gen. Metz made no mention of troop levels, but said that Gen. Batiste could use some more unmanned spy planes and Iraqi linguists, the 2004 AP report says.

Today Gen. Batiste says the encounter left him furious with Mr. Rumsfeld. "We had fought and argued about these issues internally ad nauseam and a decision had been made ... . You get what you get and do the best you can. I am not going to air our dirty laundry in public. That is our culture," he says. "It was an outrageous question and he knew I couldn't give him an honest answer in a public forum. I felt as though I had been used politically."

Larry Di Rita, a senior aide to Mr. Rumsfeld, who also attended the meeting, says if Gen. Batiste "had something stuck in his craw, he had ample opportunity" to ask for private time with Mr. Rumsfeld. He says Mr. Rumsfeld blocked out two hours to spend with Gen. Batiste and his troops. "The opportunity was there if there was something he wanted to bring up."

During that meeting, Mr. Di Rita says Gen. Batiste was "upbeat" on progress in his area. "It was an extremely positive interaction," Mr. Di Rita says. He says he finds Gen. Batiste's recent criticism of the secretary "baffling."

Mr. Rumsfeld has consistently touted the virtues of a smaller, faster force, which he says allowed the U.S. to topple Saddam Hussein more quickly. He also has said that a larger force, of the sort advocated by Gen. Batiste, would breed a culture of dependency and resentment among the Iraqis. The better solution, he insisted, was to use a smaller force that would help the Iraqis to stabilize and rebuild the country themselves.

Gen. Batiste's division returned to Germany in February 2005. Despite challenges, he believed he was winning the war in his region. "I thought we had turned a corner," he says today.

He and his family went to Malawi for several weeks to camp and visit his daughter in the Peace Corps. In April, he was offered a job as the deputy commander of the Army's V Corps, a major warfighting command, and told that when the Corps deployed to Iraq in early 2006 he likely would be given a third star, according to Army officials. The promotion would have made him the second-highest ranking military officer in Iraq, overseeing about 130,000 troops.

Despite misgivings, he accepted the job. Gen. Batiste was on course to assume the deputy corps commander position, after he relinquished command of his division. His wife traveled to Heidelberg to visit their new home. But Gen. Batiste began to think hard about resigning. "How can I look myself in the mirror if I take this job," he recalls thinking.

Gen. Batiste barely slept in the days leading up to the change-of-command ceremony, he says, often pacing around his house. He was haunted by something he had studied during his days at the Army War College: the regrets of Gen. Harold K. Johnson, the Army chief of staff during the Vietnam War.

Years after he retired, Gen. Johnson told friends that at one point during the war, he planned to confront President Lyndon Johnson and quit, according to a biography by Lewis Sorley, a retired Army officer and Vietnam scholar.

"You have required me to send men into battle with little hope of the ultimate victory and you have forced us to violate almost every one of the principles of war in Vietnam," Gen. Johnson planned to tell the president, the biography says. "Therefore I resign and will hold a press conference after I walk out your door."

He never did. Before he died, Gen. Johnson lamented that he was going to his grave "with the burden of a lapse of moral courage on my back," according to the biography.

That account supports a belief -- held by many in the Army today -- that the U.S. military lost in Vietnam because it was betrayed by ill-informed politicians who disregarded their advice.

Many historians, including Army Col. H.R. McMaster, who wrote Dereliction of Duty, a history of the top brass in Vietnam, say the truth is more complicated. Col. McMaster argues that the generals, split by rivalries and eager to curry favor with their civilian bosses, acquiesced to a policy they knew would fail in Vietnam, without raising serious objections or offering alternate strategy.

For a general to publicly disagree with civilian leaders can mean the end of a career. In one famous case, Gen. Douglas MacArthur was fired by President Truman after expressing his desire to take the Korean War further than the administration wanted.

Gen. Batiste says he had raised concerns within his chain of command. But he felt he needed to do more. On June 19, the day before the change-of-command ceremony, he filled out a retirement form on his computer and faxed it to his four-star commander in Germany.

The next day, Gen. Batiste, speaking at the ceremony, began his protest — but in a way so oblique that only his closest friends would understand. He told the hundreds in attendance that the 1st Infantry Division soldiers had succeeded in Iraq because they had "rigidly adhered to the principles of our war fighting training and doctrine."

He says that was a reference to something he had privately discussed with fellow officers: his belief that Mr. Rumsfeld had violated a fundamental principle of war by sending in an invading force that was too small to impose security after Saddam Hussein's regime had collapsed.

"The guys who knew me well understood what I was saying," Gen. Batiste says.

A few weeks later, he came back to the U.S. and in November, took a job as president of Klein Steel Services, a family-owned company that cuts custom-made steel in Rochester, N.Y. He found the job through an organization that matches retired senior military officials with companies. Gen. Batiste says he liked Klein's leadership philosophy. He also liked that the company did no defense industry work. "I wanted a clean break," he says.

His return to the U.S. was jarring. "It shocked me that the country was not mobilized for war," he says. "It was almost surreal." For some Americans, "the only time they think about the war is when they decide what color magnet ribbon to put on the back of their car."

This March, the Rochester Rotary Club asked Gen. Batiste to give a speech about the war in Iraq. He had been wrestling with whether to speak out about his frustrations. "I was teetering," he says.

Days before his April 4 talk, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said the U.S. had made thousands of "tactical errors" in Iraq. The remark, which he interpreted as a criticism of the military, upset him immensely. He decided it was time to speak out. At the time, two generals had already called for Mr. Rumsfeld's resignation.

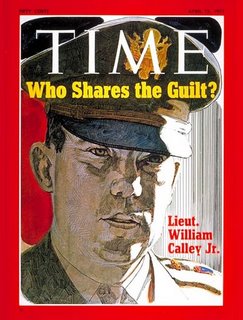

In his Rotary Club speech, Gen. Batiste didn't say Mr. Rumsfeld should quit. Instead, he called the defense secretary "arrogant," and chided him for ignoring senior military advisers. The 100 or so Rotary Club members gave him a standing ovation and the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle ran a brief article on the speech. On April 9, retired Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Gregory Newbold called for Mr. Rumsfeld to resign in a Time magazine opinion piece. He was the third general to demand Mr. Rumsfeld leave.

Two days later, a producer from CNN, who had seen the article on Gen. Batiste's Rotary Club speech, asked him if he would appear on the network. On CNN, Gen. Batiste praised the U.S. military and bemoaned the American people's lack of sacrifice and commitment to the war. Finally, he called for a "fresh start" in the Pentagon.

"We need a leader who understands team work," Gen. Batiste said. "When decisions are made without taking into account sound military recommendations...we're bound to make mistakes."

"So the secretary should step down?" the host asked.

"In my opinion, yes," Gen. Batiste replied, making him the fourth general to call for Mr. Rumsfeld to leave.

The next day he was asked on PBS if his protest was a "one-shot deal." "I have never quit anything in my life," Gen. Batiste replied.

Gen. Batiste has walked a fine line since launching his public protest. He believes it is OK for him to call for Mr. Rumsfeld's resignation. But the oath he swore throughout his 31-year Army career to "obey the orders of the president" has convinced him that he shouldn't slight President Bush. "I support my president," he says.

To some, that doesn't make sense. "Who are we kidding? It is a distinction without a difference," says Richard Kohn, a professor of military history at the University of North Carolina. Since the president has said he supports Mr. Rumsfeld, "for Gen. Batiste to speak out is to contradict the president. It is his right, legally and constitutionally. But in my opinion, it is not appropriate or consonant with a professional military career." Public protests by retired generals politicize the Army and undermine respect for the leadership among serving soldiers, he says.

Blaming civilian leaders for the woes in Iraq will prevent the Army from addressing its own failures, in preparing to fight guerrilla wars, others say. "This is a shared responsibility. The civilians didn't just do this to us. We did it to ourselves," says Gen. Jack Keane, who served as the No. 2 officer in the Army during much of the planning and early days of the war.

Gen. Batiste has continued to publicly call for Mr. Rumsfeld's resignation, saying he has a "moral obligation" to speak out both for his troops, some of whom are back in Iraq, and his nation.

"My objective is accountability. I think Mr. Rumsfeld's decisions have caused our military almost irreparable harm," he says. "Sadly, I can do more for soldiers outside the military right now than inside."

Greg Jaffe

Copyright © 2006 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

Get an RSS (Really Simple Syndication) Reader at no cost from Google at Google Reader. Another free Reader is available at RSS Reader.

Get an RSS (Really Simple Syndication) Reader at no cost from Google at Google Reader. Another free Reader is available at RSS Reader.