One of the first books that set me on course to study history through three degrees at three different colleges was The American Political Tradition And The Men Who Made It. If I had a hero among historians, it was Richard Hofstadter. If this is (fair & balanced) hero worship, so be it.

[x TNR]

What Was Liberal History?

by Sean Wilentz

Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography

By David S. Brown

(University of Chicago Press, 291 pp., $27.50)

I.

In March 1965, a delegation of historians joined Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s fifty-four-mile march from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama. Weeks earlier, Alabama state troopers had brutally broken up a voting rights march in Selma with nightsticks and tear gas, and King aimed to finish what the protesters had started. The historians, who included the renowned Richard Hofstadter, went south to take a stand. That the normally circumspect Hofstadter struck his tasks at Columbia University and made the trip suggested just how deep the outrage at Jim Crow repression had become.

Hofstadter, in character, acted more the dry wit than the rabble-rouser. At one point, the bus carrying the scholars to the march swerved badly, leaving the professors momentarily shaken and frightened. Hofstadter broke the tension. "If your driving leads to an accident that kills us all," he pleaded with the bus driver, "you will set back the liberal interpretation of American history for a century!"

His tone was, as ever, ironic and humorous, but it was also charged with energy and pride. "I had the feeling that he felt liberated," one of his colleagues recalled, "that he was somehow getting in touch with the past." Hofstadter would have been even prouder had he known that one of the leaders of the original march, John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, had been carrying a small knapsack when a state trooper cracked open his skull, and that inside the knapsack was a paperback copy of The American Political Tradition, Hofstadter's most widely read book, published seventeen years earlier.

As David S. Brown claims in this illuminating biography, Hofstadter retains an enormous mystique today, thirty-six years after his death from leukemia at the age of fifty-four. Phrases and concepts that Hofstadter invented to describe and to analyze American politics--"status anxiety," "the paranoid style"-- remain in currency among high-end journalists and pundits. His best books, The American Political Tradition and The Age of Reform, remain on graduate reading lists decades after their publication, models of dazzling prose and interpretive acuity. All but one of his half-dozen other major works remain in print.

In some respects, indeed, Hofstadter's standing has risen since 1970. His fascination with the history of what he called "political culture," the quirks in American politics beyond official platforms and speeches, is now very much in vogue. And no historian of the United States with the same combination of intellectual heterodoxy, literary brilliance, and scholarly sweep has replaced him. Amid the current dizzy political scene--with its snake-oil preachers, and anti-Darwinian Social Darwinists, and Indian casino ripoff artists, and a president whose friends say he thinks he is ordained by God--Hofstadter's sharpness about the darker follies of American democracy seems more urgently needed than ever.

Brown's labors would have been worthwhile had he simply told the man's life story and assessed his work. (The only previous book on Hofstadter confines itself to his leftist youth in the 1930s, including a brief and uneasy membership in the Communist Party.) But Brown goes further, describing Hofstadter's paradoxical mixture of iconoclasm and caution, a personality that managed to submerge melancholy in ambition and a sense of the absurd. Brown's book freshens the worn-out chronicle of the postwar Upper West Side intelligentsia by re-telling it from Hofstadter's playful, eternally skeptical, oddly uninflammatory point of view. Although he was essentially a private intellectual and writer--"I'm not a teacher," he once told his student Eric Foner, "I'm a writer"--Hofstadter emerges here as more engaged in the politics of the 1950s and 1960s than is often remembered. If Brown at times makes his subject seem too reactive, his thinking a product of the larger academic and political world, he captures Hofstadter's evolving thoughts without pigeonholing them; and he attends to how fortune--good, bad, and heartbreaking--altered the course of Hofstadter's achievements.

Above all, Brown helps readers assess Hofstadter as a member of a generation of American historians every bit as important as (and in some respects more so than) the well-known Progressive generation of Charles Beard, Frederick Jackson Turner, and Vernon Parrington, the trio to whom Hofstadter devoted his last full-scale book. Like those earlier scholars, Hofstadter's generation, which included Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and C. Vann Woodward, imagined history as a continuing dialogue between the past and the present. Although many came to the academy as outsiders (Schlesinger being an obvious exception), all were highly respectful of the spirit--if not always the institutions and the rituals--of the scholarly life.

In other important ways, to be sure, the liberal historians of mid-century America defy easy generalization. In temperament, they differed greatly, not least in their respective affinity for power, whether inside or outside the academy. Schlesinger served in the White House during the Kennedy years, as another prominent liberal historian, Eric Goldman of Princeton, did under Lyndon B. Johnson. Although Woodward was less drawn to the political limelight, he worked on behalf of the House Judiciary Committee during the Watergate scandals and served as president of the American Historical Association, the Organization of American Historians, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Hofstadter, by contrast, seemed allergic to holding official power of any kind, and turned down the only White House appointment offered him, and rarely attended professional meetings.

Nor can the liberals be shoehorned into the category of "consensus" historians, a tag all too frequently affixed to the post- World War II generation of Americanists. The label did suit Hofstadter for a time--in some respects he invented the consensus genre--even though it eventually troubled him. But although they rejected the Progressives' simplistic understanding of American conflict as an unending struggle between "agrarianism" and "industrialism," neither Schlesinger nor Woodward nor their many admirers wrote of an overarching consensus in our past. Quite the opposite.

The liberal historians converged in trying to reconstruct the nation's history in the shattering wake of the New Deal, World War II, the Cold War (and, especially in Hofstadter's case, McCarthyism), and finally the civil rights movement. Without abandoning the Progressive idea of a "usable" past--Woodward (frowning, then smiling, eyebrows arched) once remarked that a usable history would always be preferable to a useless one--the liberals brought to American history what Lionel Trilling famously called a sense of "variousness, possibility, complexity, and difficulty," which had eluded their elders. Schlesinger, for his part, adapted liberal anti-communist ideas drawn from Reinhold Niebuhr, who mocked the optimistic naïveté of Progressive historiography and instead valued a secularized and historicized idea of original sin. Woodward concentrated on his native South, noting the stark discontinuities as well as the continuities in southern history, discovering longobscured southern paradoxes of class, race, and party, and re-interpreting the history and the legacy of slavery as part of what he called an intricate and often ironic "American counterpoint" between the sections.

What made the writings of these historians liberal? This liberalism originated in a twofold desire. First, in the most precise sense of liberal as large, generous, capacious, these historians wanted to be more inclusive, examining aspects of American political and social life that previous historians had slighted, from race and ethnicity to the power of irrational symbolic appeals. Second, they wanted to re-interpret a liberal tradition that they believed had dominated American history more critically, freed from the self-ratifying pieties of much liberal historiography as well as from the deceptive, often manipulative populism that characterized the 1930s and 1940s Popular Front left.

Looking back, they appear, in keeping with the political trends of their formative and middle years, to have badly overestimated liberalism's dominance of the American political tradition. Much of their writing through the 1970s did little to prepare readers for the conservative era that was to come. Still, they rendered the writing of American history far more intellectually strenuous and much less predicable than ever before. They produced a body of scholarship that, if not as magisterial as the Annales school in France, did much to affect civic life and political sensibilities in their own country. And among these talented, driven scholar-intellectuals, the sometimes conflicted mind of Richard Hofstadter was the boldest of all.

II.

Nothing can be understood about Hofstadter's intelligence without understanding his visceral urban proclivities, inflected by his aversion to the smug absolutism that too often afflicted big-city intellectuals. Much of the so-called "counter-Progressive" historiography of the 1940s and 1950s rebelled against the Midwestern biases of the previous generation, which beheld the nation's cities as sinks of political and economic corruption. Turner, raised and schooled in Wisconsin, had rendered the frontier West as the seedbed of American democracy. Parrington, a product of Kansas, elucidated all of American thought as a battle between Jeffersonian rural individualism and Hamiltonian urban plutocracy. Beard, born in Knightstown, Indiana, was somewhat different, seeing American history as a war among economic interests that sometimes cut across the urban-rural divide; and Hofstadter always accorded Beard the greatest respect among his elders. Yet Beard, too, tended to associate the industrializing, cash-driven, urban North (and especially the Northeast) as the main source of the nation's sordidness. The Rise of American Civilization (published in 1927, and co-authored with Beard's wife, Mary Ritter Beard) described the Civil War as "the Second American Revolution" less because it freed the slaves--to the Beards, a bogus moral issue--than because northern "industry as well as finance had its reward" in the demise of the Old South, leading to the degrading excesses of the Gilded Age.

Hofstadter was spared any nostalgic yearning for the American agrarian myth. He was born in 1916 in Buffalo, to a lower-middle-class Polish-Jewish father and a German Lutheran mother. A polyglot provincial city, Buffalo lacked the frontier remnants that shaped the Progressive generation--but it also lacked the relentless, know-it-all kinetics that propelled ambitious metropolitan immigrants who also came of age in the 1930s, and made them vulnerable to left-wing sectarianism. Drawn early to philosophy as well as to history, Hofstadter studied as an undergraduate at the University of Buffalo with Julius W. Pratt, a prominent diplomatic and intellectual historian best known for his writings on the emotional and psychological factors that drove American expansionism. Since he challenged national pieties, Pratt is sometimes described as one of the Progressives; and so his influence in shaping Hofstadter is too often overlooked, especially in casting doubt on the Beards' preoccupation with material factors in history. (Hofstadter's undergraduate thesis, which became the basis for his first professional article, refuted the Beardian interpretation of the Civil War's origins.)

At Buffalo, Hofstadter joined the radical left. An active member and eventually Buffalo chapter president of the National Student League, the dominant campus left-wing organization of the time, he participated in a nationwide student antiwar strike of classes in April 1935. He fell in love with and married Felice Swados, a fellow left-wing student and committed activist (and the sister of Harvey Swados, later known as a fine fiction writer and essayist). Over the objection of family members, he decided against becoming a lawyer, began taking courses in Columbia's history department in 1937, and wrote an M.A. thesis that berated, from a leftist perspective, the New Deal's Agricultural Adjustment Act. In 1942, he completed the dissertation that would become his first book, a scathing survey of capitalist apologia, Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860-1915. He also attended, with Felice, meetings of the Young Communist League, and in October 1938 he dutifully enlisted in the Columbia graduate unit of the Communist Party. "I don't like capitalism and want to get rid of it," he wrote.

Appalled by the communists' authoritarianism and, Brown suggests, by reports on the Moscow trials, Hofstadter abruptly quit the party after only four months, but for years thereafter he appears to have considered himself a man of the radical left. His Marxist phase was common for the disaffected students of his generation, and it made a lasting impression. Above all, it gave him ways to think about American politics outside the mainstream categories of liberal and conservative. From this radicalized perspective, American politics appeared to be not an abiding battle between equality and privilege but rather a contest between political parties whose similarities overwhelmed their differences. The Marxism of the 1930s lay just below Hofstadter's oft-quoted later observation that America's egalitarianism "has been a democracy in cupidity rather than a democracy of fraternity"--a left-wing formulation that, paradoxically, also seemed to declare the futility of left-wing politics in the United States.

Hofstadter's ironic temperament and his literary turn quickly rendered him an odd man out among the comrades. Even at his most radical, he lacked the vehement self-assurance and faith in historical eschatology that drove so many others to toe the party line. Although he studied the political economy of currency policy and agricultural subsidies, he preferred analyzing the subtle play of ideas and words and images. Spiritually as well as personally, he drew closer to the anti-Stalinists in and around Partisan Review. His close friend Alfred Kazin, whom he met early on in New York, observed that imagining Hofstadter writing essays on dialectical materialism was like imagining "Pope Pius doing a striptease." Hofstadter's dalliance among the Columbia communists also left him eternally wary of the folksy "progressivism" and scapegoating "populism" that pervaded the party in its mid-1930s Popular Front incarnation. "His first skirmishes with anti-intellectualism, in other words," Brown writes, "were fought against the Left."

The force of Hofstadter's mordant outlook on social movements and American politics generally--one owing nearly as much to Mencken as to Marx--was still gathering when he published Social Darwinism in American Thought in 1944. The book is very much of its time (and, Brown suggests, actually originated in an idea of Felice Hofstadter's), but it also bears traits that would become closely identified with the historian's mature work. Hofstadter's stripping away of the moral convenience in the writings of William Graham Sumner and his followers remains a brilliant exposé of how callous, complacent claptrap can masquerade as benevolent, pseudo-scientific reason. The book's vaunting of the reformist, long out-of-fashion sociologist Lester Ward, as well as of William James and the pragmatists, located a philosophical alternative--native, practical, and non-communist--to the Anglo-Saxonism and crass individualism that Hofstadter still found persistent in America. Above all, the book skillfully deployed irony to gain perspective, showing how entrepreneurs seized upon American egalitarian principles to make their fortunes, only to use the same principles in order to justify plutocracy. The deadpan calm of Hofstadter's tone made it all the more corrosive.

Only twenty-eight when the book appeared, Hofstadter had already begun his rise through the academic ranks, having traded a job at City College for a position at the University of Maryland in 1942. Felice gave birth to a son at the end of 1943. Spared from the military draft because of allergies and digestive troubles, Hofstadter taught soldiers and traded ideas with talented young colleagues (including Kenneth Stampp and C. Wright Mills) in College Park before he got the call in 1946 to return to Columbia, where he would spend the rest of his career. By then, he was well into writing a new book, a series of biographical portraits with the working title Men and Ideas in American Politics.

Yet as Brown carefully details, Hofstadter's early progress contained ironies of its own, punctuated by both chance successes and catastrophe. His first post, at City College, came open only after a Red Scare purge of suspect faculty members. Hofstadter won the Maryland position in part because anti-Semitism, still a bane of the historical profession, precluded the school from hiring a rival with a more Jewish-sounding name. (It was Eric Goldman.) Four years later, Hofstadter was passed over at Johns Hopkins because he was half-Jewish--and the job went instead to C. Vann Woodward, who would become a close friend and a sympathetic critic.

Hofstadter's early chapters of Men and Ideas met with a swift rejection from a minor publisher, only to win enthusiastic acceptance, and a cash fellowship to boot, from Alfred A. Knopf in 1945. Yet that wonderful break came to a man working impossibly hard amid sudden devastation. In the spring of 1944, Felice was diagnosed with cancer. Consumed with caring for his wife and infant son, Hofstadter managed to obtain a paid leave from Maryland and join his family in Buffalo, where Felice died in July 1945. Hofstadter took refuge in writing his new book, but the prospects looked bleak; and with the medical bills piling up, he considered leaving the underpaid professoriat for a career in journalism. Except for Knopf's sharp eye and the Columbia historians' decision to hire him instead of another formidable candidate, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Hofstadter might have been lost to scholarship--and the manuscript of what came to be re-titled The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It might never have seen print.

III.

It is unorthodox; it will outrage many people," the Knopf awards committee said of Hofstadter's manuscript. "But no one will deny its distinction." The committee strongly (and mistakenly) doubted that a book of biographical essays would succeed commercially, but it gave Hofstadter the award anyway. The book's editor helped to prove the group wrong by backing Alfred Knopf's argument that it needed a strong introduction to pull together the author's disparate themes. Often forgotten is that the author was passing through a crisis. Hofstadter later confessed that the main reason he had avoided writing an introduction was that "I was in a period of intellectual transition," and fully aware that he was in no position to write "a synthetic statement about the American political tradition."

The move back to Columbia in 1946 pushed many of his earlier loyalties and affinities to the background. The place itself had changed from the radical testing ground of the Depression years to the cradle of what would become a more skeptical 1950s liberalism, associated with, among others, Lionel Trilling and Jacques Barzun. In the summer of 1946, Hofstadter fell in love with Beatrice Kevitt, a war widow, fellow Buffalo native, and trained classicist who was trying to start over as a writer in New York, and six months later they married. Knopf, meanwhile, became his powerful ally in the publishing world, as he would remain for the rest of Hofstadter's life. The brilliant but bereft and nearly thwarted scholar was becoming a Manhattan intellectual insider. His manuscript, conceived and largely written by a man of the left, was being completed by a man of leftish but no longer firmly radical convictions.

The long-evaded introduction began by disparaging the upbeat, entertaining Americana that had come to dominate popular historical studies--a quest for the past "carried on in a spirit of sentimental appreciation rather than of critical analysis." Hofstadter blamed the escapist mood on an insecurity in the American soul, rocked by the Great Depression and World War II, which had upset the climate of common political values that had dominated the nation since its founding. By examining the old central faith, "bounded by the horizons of property and enterprise," Hofstadter found that the legendary battles so dear to the Progressives, between Federalist capitalists and Jeffersonian democrats, Whig businessmen and Jacksonian plebeians, amounted to far less than met the eye. Whatever genuine differences and conflicts divided the nation's political leaders, "the business of politics" had always been to "protect this competitive world [that is, capitalism], to foster it on occasion, to patch up its incidental abuses, but not to cripple it with a plan for common collective action." That consensus, Hofstadter proclaimed, had become intellectually bankrupt and unreal--a tough-minded view of American politics, especially liberal politics, from the left that challenged many liberal (and even leftist) sacred cows.

Most of the book re-interpreted liberal heroes from Thomas Jefferson through Franklin Delano Roosevelt, bringing each luminary crashing down out of the clouds by insisting that nearly all American politicians "accepted the economic virtues of capitalist culture as necessary virtues of man." Hofstadter's irony performed a great deal of work, as he depicted his subjects less as paragons than as paradoxes. Jefferson was, in Hofstadter's formulation, "the Aristocrat as Democrat"; Andrew Jackson, the supposed democratic tribune of the common man, turned out to be an advance agent of liberal capitalism in its most cut-throat, laissez-faire form. Theodore Roosevelt was "the Conservative as Progressive." In The American Political Tradition, many Americans read of Abraham Lincoln for the first time as a conniving, self-made man whose views on race, by modern standards, were less than elevated (and whose Emancipation Proclamation, Hofstadter wrote, "had all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading").

An exception to Hofstadter's iconoclasm--and he was just a partial exception--was FDR, whose New Deal had once been an object of Hofstadter's scorn. By 1948, Hofstadter had softened considerably, finding in what he saw as Roosevelt's recognition of the passing of older forms of American opportunity a frank realization that "in cold terms ... the great era of individualism, expansion, and opportunity was dead." The book finally judged the New Deal a failure in combating the Great Depression. Its very last paragraph bemoaned the liberal cult of FDR's shimmering personality, which had only grown since the president's death three years earlier. But Hofstadter found in Roosevelt's administrations a few rays pointing out an escape route from ossified Jeffersonian liberal individualism.

As early six decades later, many of the historical judgments in The American Political Tradition appear contrarian to the point of being shallow. Jackson, who believed the federal government, not the banks, should control the currency, was no precursor of the robber barons. The book slights Lincoln's deep disgust at slavery, effaces his belief--unyielding after 1854--that the institution had to be put on the road to extinction as soon as possible, and tries too hard to turn him into a pseudo-philosophical "self-help" forerunner of Dale Carnegie. Compared with Schlesinger's The Age of Jackson (which was published in 1945, and defied the Progressives by rendering the Jacksonian era as more of a struggle between classes than between sections) and Woodward's Origins of the New South (which appeared in 1951, and rejected the Progressives' praise of Midwestern Populism while vaunting the Populism rooted in the South), The American Political Tradition had too little good to say about major American politicians and political movements. Hofstadter later admitted as much.

But its very iconoclasm, beholden neither to patriotic myth nor to left-wing romance, made The American Political Tradition enormously invigorating in its time, especially but not at all exclusively among an emerging cohort of liberal historians. Woodward praised the many "penetrating things" Hofstadter had to say; Schlesinger called the book "important and refreshing," and singled out Hofstadter as "a new talent of first-rate ability in the writing of American history." Thanks largely to Hofstadter's witty, compact, caustic prose, the book also became a popular success, featured on drugstore paperback racks as well as on high school and college reading lists for decades to come. (And, in 1965, John Lewis packed it away in his knapsack.) It remains today the centerpiece of the liberal generation's collective output, on a par with the Beards' fabulously successful The Rise of American Civilization. More than a million copies are in print. Even when Hofstadter's drubbings of American political thought are wrongheaded or excessive, the book pierces myths that still cloud our debates and short-circuit our thinking--the frontier, self-help, the Common Man, Jesus Christ as a Founding Father.

IV.

Basking in his book's success, Hofstadter became one of the pillars of a burgeoning Morningside Heights intellectual community, centered at Columbia but deeply cosmopolitan and genuinely indifferent to the academicism that knew primarily the monograph and the professional association meeting. Many of his former friends and teachers feared that he was drifting too far and too fast to the right, and tilting toward Establishment mandarin hauteur. Hofstadter's continuing work, especially The Age of Reform: From Bryan to FDR, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1955, lent the criticisms superficial credence. But if Hofstadter had outgrown the leftist spirit of the 1930s, he still wrote broadly from the left, fascinated as ever by the irrational myths that afflicted American politics, hoping to aid the forces of reform by stripping them of their illusions. With a new family, a prestigious job, and a skyrocketing reputation, Hofstadter was certainly more settled, but he remained resistant to intellectual absolutes and smug self-importance. Although he wrote history in a different key, in many respects he had changed less than the times had.

Brown's biography helps to topple the impression (which arose during the late 1960s) that after The American Political Tradition Hofstadter retreated into an ivory tower on Claremont Avenue. During the presidential campaign in 1952, at some risk to his standing on campus, Hofstadter helped organize Columbia Faculty Volunteers for Stevenson, which ran a full-page ad in The New York Times (Hofstadter drafted part of the text, Peter Gay solicited the necessary funds) protesting the paper's endorsement of Adlai Stevenson's opponent, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who just happened to be president of Columbia. Never again would Hofstadter find himself so drawn to a presidential candidate as he was to Stevenson; and he later regretted using his connection to Columbia to help advance his political views. But neither did he withdraw from writing about contemporary politics, nor did he come to believe that professional integrity demanded that historians abdicate their civic role.

Although deeply committed to scholarship, Hofstadter would, in later years, find time to raise his voice in venues ranging from Partisan Review to Newsweek, shedding what historical light he could on continuing political affairs. He became especially agitated in 1964 when the Goldwater campaign raised, in his mind, the specter of a new radical right that, he wrote in The New York Times, had already forced the Republican Party to surrender meekly, if only temporarily, "to archaic notions and disastrous leadership." Hofstadter took great--and, as it happened, premature--satisfaction when Goldwater lost in a landslide. He was overly confident in America's permanent liberal aegis.

The change in the historical questions that he asked grew from the widespread concerns of liberals and leftists shaken by the devastation of both fascism and Stalinism abroad, and, in time, by the success of Joseph R. McCarthy and other right-wing demagogues at home. The first substantial response from the young historians, Arthur Schlesinger Jr.'s The Vital Center, appeared in 1948--a political defense of what Schlesinger called "the free left" against the pro-Soviet fellow traveling exemplified by the Henry Wallace Progressive Party campaign of the same year. Hofstadter, at Columbia, was more attracted to the theorizing of diverse social scientists (including the Columbia sociologists Daniel Bell, Robert Merton, and C. Wright Mills) about the relative importance of psychological and even irrational factors in social life. Amid the McCarthyite eruptions of the early and mid-1950s, Hofstadter immersed himself in his friends' and colleagues' debates on the effects of symbolism, "status," and "latent functions" in political life, sometimes spurred by the writings of (among others) Freud, Mannheim, and Adorno. But Hofstadter's thinking also drew on his old suspicions, dating back to his days studying with Julius Pratt, that psychological and emotional pressures explained as much and maybe more about the past than economics did. He brought all those interests to bear in The Age of Reform.

Still one of the most influential books on twentieth-century America, The Age of Reform is a journey through the less savory, often hidden themes in protest and reformist politics from the Populist movement through the New Deal. The Populists come off the worst, driven by economic hardship to endorse all sorts of cranky, conspiratorial, and bigoted notions, some blatantly anti-Semitic, about the sources of rural oppression. Although every bit as commercially minded as other Americans, Hofstadter charged, the rebel farmers wrapped themselves in the fanciful mantle of the injured little Jeffersonian yeoman--an illusion that left Populism vulnerable to crude social nostrums and an anxious, destructive self-righteousness. Hofstadter saw the Progressive movement, at least at its core, as a collection of displaced patricians and intellectuals, fretful about their own social status. The Progressives were less flamboyantly conspiracy-prone than the Populists, but they were trapped nevertheless by nostalgic fantasies about restoring their own moral authority, and with it an imagined bygone America with "a rather broad diffusion of wealth, status, and power."

The book's opening sections on the Populists and the Progressives were as iconoclastic as anything in The American Political Tradition, but they raised greater doubts among his fellow liberals. Woodward (who thought his friend had gone overboard in his enthusiasm for social science) calmly but firmly replied that the Populist heritage, especially its southern branch, should not be reduced to its crankier elements. Subsequent studies of Progressivism found that Hofstadter's sweeping claims about the loose-knit movement's motives and social origins were greatly simplified. More broadly, Hofstadter's efforts to make his material cohere into a dichotomy of "interest" versus "status" were far too pat, slighting the power of ideals about fairness and justice that had nothing to do with either economic self-interest or status anxieties.

The Age of Reform's greatest achievement, often overlooked, is in its reappraisal of the New Deal, reviving and reinforcing the more positive passages in The American Political Tradition. Whereas most historians (and many New Dealers) saw Roosevelt's reforms as a continuation of Populism and Progressivism, Hofstadter affirmed the New Deal as a sharp break with the past. The old sentimental, quixotic, and self-deluding forays against capitalism gave way to Keynesian policy and the provision of social welfare. Nineteenth-century individualism and anti-monopolism fell before a fuller appreciation of the inevitable size and scope of American business. Cities and urban life, including the party political machines, which had been the bane of Jeffersonian liberalism, became an accepted, even vaunted element in the New Deal coalition. Under FDR, in short, American liberalism came of age.

Following the long-term abandonment, at least philosophically, of New Deal liberalism by both major political parties, Hofstadter's account of the New Deal's spirit repays a new look--not as an exercise in nostalgia but in order to help recover and refurbish a suppressed but still essential American political tradition. As was his wont, Hofstadter overstated his case, underestimating both the intense social conflicts that helped push the reforms forward and the degree to which Progressive ideas (particularly in the area of labor reform) guided New Deal thinking. But simply by identifying the change and by portraying what Hofstadter called the New Deal's "chaos of experimentation" as a sign of vibrancy, not weakness, The Age of Reform concisely defined the transformation of modern American liberalism, two years before Schlesinger took up the issue, in much greater detail, in The Crisis of the Old Order, 1919-1933. For that, apart from everything else, Hofstadter's book retains some of its old luster--and has even acquired a new urgency.

V.

The Age of Reform won Hofstadter the Pulitzer Prize, but he did not rest on his laurels. Still concerned with the irrational in American populist politics, and with how Americans had come increasingly to denigrate "egghead" intellectuals, he wrote a lengthy historical account, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, which won him another Pulitzer in 1963. An essay originally published in Harper's magazine, "The Paranoid Style in American Politics," became the starting point for scholars and pundits seeking historical explanations of the rising right-wing politics of the 1960s, as it has remained for writers on subjects ranging from Ross Perot to the modern survivalist movement. In 1968, Hofstadter published a fine book of historiography, The Progressive Historians: Turner, Beard, Parrington, settling his intellectual accounts with the generation before him while signaling to the up-and-coming generation his misgivings about the "consensus" history to which he had often been linked. In the interim, he returned fleetingly to speaking out on current affairs, expressing alarm at Goldwater's candidacy in 1964, opposing the Johnson administration's Vietnam policies, and defending the academy from the misdirected rage and anti-intellectualism of the New Left radicals.

For all Hofstadter's energy, though, his scholarly work in many ways lost touch with the political currents of the time. The years from 1955 to 1968 mark off exactly the period of the civil rights movement's rise, breakthrough, and descent into bitterness and confusion. Hofstadter certainly supported the movement, making his trip to Alabama. But the ex-Marxist urbanite had only occasionally showed much interest in studying southern history, or in the roles that slavery and race played in American history. Apart from a sharp chapter on John C. Calhoun in The American Political Tradition, his most extended publication on these matters, a devastating article on the racist southern historian U.B. Phillips and the plantation myth, dated back to 1944.

Kenneth Stampp, Hofstadter's friend from his College Park days, did far more to place slavery at the center of historians' attentions in The Peculiar Institution, published in 1956; and it was Woodward's The Strange Career of Jim Crow, published two years earlier, that won a reputation (directly from Martin Luther King Jr.) as "the historical bible of the civil rights movement." Hofstadter, by contrast, seemed preoccupied with the issues that had inspired him during the years before and after the personal crisis that accompanied his writing of The American Political Tradition. Brown quotes the intellectual historian Dorothy Ross, another of Hofstadter's students: "His voice came out of the thirties and out of the McCarthyism of the fifties, and that world changed." Hofstadter seemed at least vaguely aware of what had happened, confiding in one colleague that Anti-Intellectualism failed to turn out as he had intended, and that the book wrote him more than he had written it. That so much of the paranoid style he found on the Goldwater right eventually turned up, with different delusions, in the late 1960s New Left was, for Hofstadter, a source not of vindication, but of gloom.

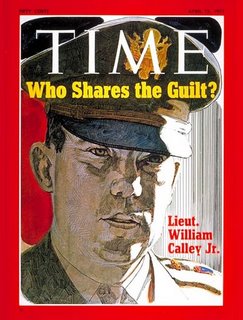

It was thus all the more remarkable, and all the more to Hofstadter's credit, that he refused to surrender to that gloom, and instead turned his prickly mind, with a certain sympathy, to the issues roiling the latest generation of American rebels. American Violence, a documentary history he compiled with his radical graduate student Michael Wallace, treated at length the seemingly singular American propensity for violent conflict, seeing it as both an outgrowth of and a limitation to his earlier considerations of mainstream political consensus, while he skewered glib diagnoses of American culture as inherently sick or depraved. Having signed on with Knopf to write a multi-volume history of the United States, he began by drafting chapters of America at 1750, in which he turned early on to the dark topics of white indentured servitude, the slave trade, and black slavery. Although still impressed with how quickly, overall, colonial America had become what he called "a middle-class world," he pushed himself to look beyond that world to the death and suffering that helped create and sustain it.

It was a poignant piece of writing, in more ways than one. In a chapter on the Great Awakening, Hofstadter paused over the fate of Jonathan Edwards, who in 1758 was named president of the College of New Jersey, today's Princeton University:

"He accepted the invitation, but shortly after reaching Princeton he was inoculated against smallpox, took the inoculation badly, and died before he could take up his duties. At the end he was puzzled by the irrationality of it all--that God should have called him to this role and then left him no time to fill it."

By the time he composed those sentences, Hofstadter had serious intimations that he was gravely ill, his writing once again serving as a refuge. He died in October 1970. America at 1750, compelling even though incomplete, was published the following year.

VI.

The New York Times's strange and grudgingly respectful obituary for Hofstadter elicited a strong rebuttal from Lionel Trilling, one of what can only be a handful of published letters to the editor ever to complain about a death notice. Far from the nondescript, methodical academic whom the Times described, Trilling said, Hofstadter was "one of the most clearly defined persons I have ever known ... an enchanting companion, almost memorably funny," who also "was notable for his openness not alone to ideas but also to people of all kinds." Not the least of the pleasures in David Brown's book are its anecdotal affirmations of Trilling's judgment, recalling Hofstadter's lifelong gift for mimicry (he did a dead-on FDR, and some friends actually encouraged him to take his talent on stage) as well as his skeptical ribbing, and sometimes scolding, of the New York intellectuals and one of their chief intellectual outlets (which he called "The New York Review of Each Others' Books").

The place of Hofstadter's scholarship in American historiography is, by contrast, assured--and, fittingly, paradoxical. Inside the academy, much of his work, even the very best of it, has come to seem, as Alan Brinkley once wrote of The Age of Reform, "something of a relic." Attacked by professional historians as often as they are praised--for their partiality, their misguided social scientific categories, their preoccupation with political leaders--Hofstadter's books undeniably bear the mark of their times, with all of the attendant limitations. Yet he has had an enduring impact on historical scholarship, as well as on more general understandings of American history. Many of his specific interpretations may now be insupportable, but his influence is inescapable. No scholar did more to free American history from the stultifying dualisms of the Progressive generation, and to validate that history's complexity. His example is a standing invitation to historical intelligence, extended to a wide audience of readers far beyond professors and their students.

Hofstadter's basic attitude toward studying the past, as much as his stylish writing, also remains worth emulating. A committed liberal, Hofstadter dedicated himself to exposing liberalism's historical flaws and its self-defeating lures and snares. A man of moral conviction, he forswore cheerleading, not simply because doing so would spoil any understanding of history, but because it ill served the ideals and standards he held most dear, including intellectual freedom and unsparing candor. Hofstadter's detractors (as well as pundits on the right who would like to claim him for themselves) have sometimes described his mature intellectual stance as "neo-conservative." This is wrong. His attitude, neither liberal nor conservative, was one of humility, based on an appreciation of human frailty and folly, and a recognition that history is more tragedy than melodrama.

Sean Wilentz is the author of The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (Norton). He also is George Henry Davis 1886 Professor of American History at Princeton University.

Copyright 2006, The New Republic

Get an RSS (Really Simple Syndication) Reader at no cost from Google at Google Reader. Another free Reader is available at RSS Reader.