IQ? (Click on image to enlarge.)

Highlight/right-click anything for Google info.

Search the blog: a search window is provided at the top of the left-side menu.

Blog Rationale: The Internet is a vast library; this blog's the best Reserve Room in that library.

Follow This Blog via E-Mail (below the blogger's profile).

Text Color/Font Code: GREEN text is written by this blogger; BROWN text (different font) is the posted article itself.

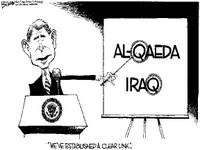

When the Trickster faced impeachment, the Rightist mantra went, FDR did it (taped Oval Office conversations), JFK did it, and LBJ did it (plus undisclosed recording of telephone conversations). Now, we are supposed to excuse the stupidity of George W. Bush because Benjamin (Pitchfork Ben) Tillman, William Henry (Old Rough and Ready) Harrison, Huey P. (the Kingfish) Long were rough- and poorly-spoken? If voters fell for Pitchfork Ben's and Old Rough and Ready's nonsense, that doesn't give them a pass. As for The Kingfish, his biographer—the late T. Harry Williams—demonstrated that Long was crazy like a fox. W—on the other hand—is dumb as a stump. Cunning, yes. But, stupid without a doubt. If this is (fair & balanced) disdain, so be it.

[x History News Network]

Keep Picking on Bush for His Bushisms.... His Handlers Love It

By Chris Bray

“Bushisms,” those much-discussed cultural artifacts that demonstrate the apparent stupidity of our poorly spoken president, really are pretty revealing. They’re also likely to backfire horribly. A couple of examples will illustrate the problem.

Ben Tillman wasn’t an ordinary farmer, but his political opponents helped him to become one. As the South Carolina politician waged a vaguely populist battle to seize control of his state’s Democratic Party through the mid-1880s and into the next decade, the well-to-do merchants and professionals who ran the party lashed out in disgust. Tillman, they noted, was boorish and without nuance, an inelegant speaker with a habit of mangling the English language.

Newspapers joined in the refrain. The Charleston News and Courier argued that Tillman’s crude politics were aimed at stirring “the passions and prejudices of the ignorant.” Responding to Tillman’s charge that an aristocracy ran the state, the newspaper petulantly agreed; it was, the paper shot back, “an aristocracy of brains and character.”

And so Tillman, who owned over 1,700 acres of farmland – far more than any struggling yeoman farmer of the day – became an ordinary guy, who didn’t talk like the overeducated aristocrats. The voting majority, who noticed that they had been repeatedly described by the reigning political elites as “ignorant,” gave their loyalty to “Pitchfork” Tillman, the plainspoken farmer. In a remarkable biography of Tillman, from which this account has been taken, the historian Stephen Kantrowitz notes one of the central ironies of his rise to power: “When his adversaries used his behavior and his followers as proof of Tillman’s demagoguery and disreputability, they revealed their own profoundly elitist notions of citizenship and leadership.”

The Kerry campaign – and everyone else in politics, while we’re at it – should paint that cogent sentence on the wall of their headquarters, in foot-high letters. George W. Bush’s politics are obviously very different than Tillman’s, in more ways than one, but the point is more personal than that: call someone stupid or unsophisticated, and you have to say why. That’s where things get tricky, for pretty obvious reasons.

Similar examples pop up throughout American history, reflecting a dynamic that has benefited candidates all across the political spectrum. In 1840, a Democratic reporter sneered that William Henry Harrison, the not-terribly-distinguished Whig candidate for president, would be perfectly happy to spend the rest of his days sitting around in a log cabin with a jug of hard cider. Harrison took that image to the bank, cheerfully (and falsely) agreeing that he was an ordinary man who felt plenty comfortable with simple shelter and drink; his supporters marched in parades behind mocked-up log cabins. Harrison won the election handily.

Ignoring American political history, Bush’s most virulent opposition is engaged in a staggeringly obtuse cultural offensive that defines most of the country outside their circle. Attacking his instances of inelegant speech, people who loudly and publicly hate George Bush attack the inelegant. Anyone who has spent some time around the humanities division will recall the comfortable claim that most highly educated people live on the political left. Granting that self-aggrandizing and highly debatable point for the sake of argument, we might stop to note that one American in four graduates from college – from any college, all grade-point-averages included. That’s a pretty narrow path to political success, folks. Most people can smell contempt.

So rant on, and take careful note of every stupid-sounding thing that the president says. But remember what the horrified New York Times Book Review had to say about Huey Long, the wildly successful governor and senator from Louisiana, when he published his autobiography in 1933: “There is hardly a law of English usage or a rule of English grammar that its author does not break somewhere.”

And remember one other thing: Nineteen thirty-four was a very good year for Senator Huey Long.

Chris Bray is a graduate student in history at UCLA.

Copyright © 2004 History News Network

No one ever went broke understimating the intelligence of the American people. - Karl Rove (actually) H.(enry) L. Mencken. The latest linguistic exploit of the 43rd President of the United States of America occurred during an unrehearsed aside in Poplar Bluff, MO on September 6, 2004. The President of the United States is an idiot. Read all of these direct quotes from the mouth and brain(?) of W. Then, vote for him. Who's the idiot? If this is (fair & balanced) sedition, so be it.

Bushisms: Adventures in George W. Bushspeak

"Too many good docs are getting out of the business. Too many OB-GYNs aren't able to practice their love with women all across this country." —George W. Bush, Poplar Bluff, Mo., Sept. 6, 2004

"Had we to do it over again, we would look at the consequences of catastrophic success, being so successful so fast that an enemy that should have surrendered or been done in escaped and lived to fight another day." —George W. Bush, telling Time magazine that he underestimated the Iraqi resistance

"They've seen me make decisions, they've seen me under trying times, they've seen me weep, they've seen me laugh, they've seen me hug. And they know who I am, and I believe they're comfortable with the fact that they know I'm not going to shift principles or shift positions based upon polls and focus groups." —George W. Bush, interview with USA Today, Aug. 27, 2004

"I hope you leave here and walk out and say, 'What did he say?'" —George W. Bush, Beaverton, Oregon, Aug. 13, 2004

"So community colleges are accessible, they're available, they're affordable, and their curriculums don't get stuck. In other words, if there's a need for a certain kind of worker, I presume your curriculums evolved over time." —George W. Bush, Niceville, Fla., Aug. 10, 2004

"Let me put it to you bluntly. In a changing world, we want more people to have control over your own life." —George W. Bush, Annandale, Va, Aug. 9, 2004

"As you know, we don't have relationships with Iran. I mean, that's — ever since the late '70s, we have no contacts with them, and we've totally sanctioned them. In other words, there's no sanctions — you can't — we're out of sanctions." —George W. Bush, Annandale, Va, Aug. 9, 2004

"Our enemies are innovative and resourceful, and so are we. They never stop thinking about new ways to harm our country and our people, and neither do we." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Aug. 5, 2004 (Watch video clip)

"Tribal sovereignty means that; it's sovereign. I mean, you're a — you've been given sovereignty, and you're viewed as a sovereign entity. And therefore the relationship between the federal government and tribes is one between sovereign entities." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Aug. 6, 2004 (Watch video clip)

"I cut the taxes on everybody. I didn't cut them. The Congress cut them. I asked them to cut them." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Aug. 6, 2004

"I wish I wasn't the war president. Who in the heck wants to be a war president? I don't." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Aug. 6, 2004

"We stand for things." —George W. Bush, Davenport, Iowa, Aug. 5, 2004

"Give me a chance to be your president and America will be safer and stronger and better." —Still-President George W. Bush, Marquette, Michigan, July 13, 2004

"I mean, if you've ever been a governor of a state, you understand the vast potential of broadband technology, you understand how hard it is to make sure that physics, for example, is taught in every classroom in the state. It's difficult to do. It's, like, cost-prohibitive." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., June 24, 2004

"And I am an optimistic person. I guess if you want to try to find something to be pessimistic about, you can find it, no matter how hard you look, you know?" —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., June 15, 2004

"I want to thank my friend, Senator Bill Frist, for joining us today. You're doing a heck of a job. You cut your teeth here, right? That's where you started practicing? That's good. He married a Texas girl, I want you to know. Karyn is with us. A West Texas girl, just like me." —George W. Bush, Nashville, Tenn., May 27, 2004

"I'm honored to shake the hand of a brave Iraqi citizen who had his hand cut off by Saddam Hussein." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., May 25, 2004

"Like you, I have been disgraced about what I've seen on TV that took place in prison." —George W. Bush, Parkersburg, West Virginia, May 13, 2004

"My job is to, like, think beyond the immediate." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., April 21, 2004

"This has been tough weeks in that country." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., April 13, 2004

"Coalition forces have encountered serious violence in some areas of Iraq. Our military commanders report that this violence is being insticated by three groups." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., April 13, 2004

"Obviously, I pray every day there's less casualty." —George W. Bush, Fort Hood, Texas, April 11, 2004

"Earlier today, the Libyan government released Fathi Jahmi. She's a local government official who was imprisoned in 2002 for advocating free speech and democracy." —George W. Bush, citing Jahmi, who is a man, in a speech paying tribute to women reformers during International Women's Week, Washington, D.C., March 12, 2004

"The march to war hurt the economy. Laura reminded me a while ago that remember what was on the TV screens — she calls me, 'George W.' — 'George W.' I call her, 'First Lady.' No, anyway — she said, we said, march to war on our TV screen." —George W. Bush, Bay Shore, New York, Mar. 11, 2004

"God loves you, and I love you. And you can count on both of us as a powerful message that people who wonder about their future can hear." —George W. Bush, Los Angeles, Calif., March 3, 2004

"Recession means that people's incomes, at the employer level, are going down, basically, relative to costs, people are getting laid off." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Feb. 19, 2004

"The march to war affected the people's confidence. It's hard to make investment. See, if you're a small business owner or a large business owner and you're thinking about investing, you've got to be optimistic when you invest. Except when you're marching to war, it's not a very optimistic thought, is it? In other words, it's the opposite of optimistic when you're thinking you're going to war." —George W. Bush, Springfield, Mo., Feb. 9, 2004

"But the true strength of America is found in the hearts and souls of people like Travis, people who are willing to love their neighbor, just like they would like to love themselves." —George W. Bush, Springfield, Mo., Feb. 9, 2004

"In my judgment, when the United States says there will be serious consequences, and if there isn't serious consequences, it creates adverse consequences." —George W. Bush, Meet the Press, Feb. 8, 2004

"There is no such thing necessarily in a dictatorial regime of iron-clad absolutely solid evidence. The evidence I had was the best possible evidence that he had a weapon." —George W. Bush, Meet the Press, Feb. 8, 2004

"The recession started upon my arrival. It could have been — some say February, some say March, some speculate maybe earlier it started — but nevertheless, it happened as we showed up here. The attacks on our country affected our economy. Corporate scandals affected the confidence of people and therefore affected the economy. My decision on Iraq, this kind of march to war, affected the economy." —George W. Bush, Meet the Press, Feb. 8, 2004

"My views are one that speaks to freedom." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Jan. 29, 2004

"See, one of the interesting things in the Oval Office — I love to bring people into the Oval Office — right around the corner from here — and say, this is where I office, but I want you to know the office is always bigger than the person." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Jan. 29, 2004

"More Muslims have died at the hands of killers than — I say more Muslims — a lot of Muslims have died — I don't know the exact count — at Istanbul. Look at these different places around the world where there's been tremendous death and destruction because killers kill." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Jan. 29, 2004

"Then you wake up at the high school level and find out that the illiteracy level of our children are appalling." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Jan. 23, 2004

"Just remember it's the birds that's supposed to suffer, not the hunter." —George W. Bush, advising quail hunter and New Mexico Sen. Pete Domenici, Roswell, N.M., Jan. 22, 2004

"I want to thank the astronauts who are with us, the courageous spacial entrepreneurs who set such a wonderful example for the young of our country." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C. Jan. 14, 2004

"I was a prisoner too, but for bad reasons." —George W. Bush, to Argentine President Nestor Kirchner, on being told that all but one of the Argentine delegates to a summit meeting were imprisoned during the military dictatorship, Monterrey, Mexico, Jan. 13, 2004

"One of the most meaningful things that's happened to me since I've been the governor — the president — governor — president. Oops. Ex-governor. I went to Bethesda Naval Hospital to give a fellow a Purple Heart, and at the same moment I watched him—get a Purple Heart for action in Iraq — and at that same — right after I gave him the Purple Heart, he was sworn in as a citizen of the United States — a Mexican citizen, now a United States citizen." —George W. Bush, Washington, D.C., Jan. 9, 2004

"And if you're interested in the quality of education and you're paying attention to what you hear at Laclede, why don't you volunteer? Why don't you mentor a child how to read?" —George W. Bush, St. Louis, Mo., Jan. 5, 2004

"So thank you for reminding me about the importance of being a good mom and a great volunteer as well." —George W. Bush, St. Louis, Mos., Jan. 5, 2004

Copyright © 2004 George W. Bush

Now, I am going to have nightmares about the Bride of Osama bin Laden. If this is (fair & balanced) misogyny, so be it.

[x International Herald Tribune]

The spectacular rise of the female terrorist

by Alexis B. Delaney and Peter R. Neumann

Another failure of imagination?

The recent wave of terrorist attacks in Russia has been remarkably brutal, aimed even at children. There was, however, another detail regularly picked up by commentators and analysts: the prominent role played by women.

When two commercial aircraft were brought down over Central Russia on Aug. 24, female terrorists carried the bombs. When a blast destroyed a Moscow railway station on Aug. 30, it was a woman who emerged as the main suspect. And in the hostage crisis in the province of North Ossetia, it was - again - women who were found among the kidnappers wearing suicide bomb belts.

Networks like Al Qaeda have always used women to carry out various auxiliary tasks, but their systematic involvement as high-profile operatives emerged only in recent years. In 2002, when Chechen terrorists took 700 hostages in a Moscow theater, 18 of the kidnappers were women. In Israel, the first female suicide bombers appeared in the same year, and groups like Islamic Jihad and Hamas have since "liberalized" their recruitment policies to allow females to join their ranks. Indeed, it was only in January of this year that a British Airways flight from London had to be canceled because a female operative planned to blow up the plane over Washington.

All this amounts to a major shift in the operational modus operandi of Islamic terrorists. The events in Russia suggest that women are now the preferred tool with which to carry out "martyrdom operations." If sustained, this would be a truly remarkable development. After all, Islamic terrorists propagate a vision of society in which women are consistently portrayed as weak, inferior and sinful. Women, they believe, have no role to play in public life, never mind that of "heroic martyr." The question, therefore, is obvious: Why have Islamic extremists suddenly embraced the use of women as high-level operatives?

Symbolically, their participation sends a powerful message, blurring the distinction between perpetrator and victim. Even among progressive Westerners, the notion that women are the "weaker sex," and that their inclination is to create and protect life rather than destroy it, remains widespread. If women decide to violate all established norms about the sanctity of human life, they do so only as a last resort. The scholar Clara Beyler, who analyzed public reactions to suicide bombings, found that "female kamikazes" tended to be portrayed as "the symbols of utter despair ... rather than the cold-blooded murderers of civilians." If a woman was involved, the media focused on "what made her do it," not on the carnage that she had created. In other words, if the attacker was a woman, it was the bomber who became the victim, and whose grievances needed to be addressed.

The second reason for the spectacular rise of female operatives is practical. After the attacks of Sept. 11, the security measures introduced at airports, train stations and other public places were geared toward the perpetrators of the hijackings. As all the members of the group around Mohammed Atta were young, male and of Middle Eastern origin (as well as appearance), it was little surprise that this became the prototype at which law enforcement agencies around the world were looking most closely. Terror networks like Al Qaeda were quick to spot this vulnerability, and consequently set out to recruit operatives who did not fit the standard description. As Jessica Stern noted, the perception that women are less prone to violence, the Islamic dress code and the reluctance to carry out body searches on Muslim women made them the "perfect demographic."

The relevance of this development extends far beyond the current crisis in Russia. In fact, our astonishment at the use of female operatives by Islamic terrorists may be yet another "failure of imagination" with potentially catastrophic consequences. As early as 2002, Patricia Pearson warned: "Yes, it may be hard to imagine a woman flying into the twin towers. But we have to be careful about our presumptions. ...Our imagination failed us before Sept. 11, and we paid a steep price."

Alexis B. Delaney is a defense analyst based in Washington. Peter R. Neumann is research fellow in international terrorism at the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Copyright © 2004 The International Herald Tribune

As The Daily Show with Jon Stewart reminded us, W's words speak louder than actions. In fact, the ultimate test for W's veracity is that he is lying when his lips are moving. Indeed, who cares about the truth? If this is (fair & balanced) conjecture, so be it.

[x The Chronicle of Higher Education]

Who Cares About the Truth?

By MICHAEL P. LYNCH

In early 2003 President Bush claimed that Iraq was attempting to purchase the materials necessary to build nuclear weapons. Although White House officials subsequently admitted they lacked adequate evidence to believe that was true, various members of the administration dismissed the issue, noting that the important thing was that the subsequent invasion of Iraq achieved stability of the region and the liberation of the country.

Many Americans apparently agreed. After all, there were other reasons to depose the Hussein regime. And the belief that Iraq was an imminent nuclear threat had rallied us together and provided an easy justification to doubters of the nobility of our cause. So what if it wasn't really true? To many, it seemed naïve to worry about something as abstract as the truth or falsity of our claims when we could concern ourselves with the things that really mattered -- such as protecting ourselves from terrorism and ensuring our access to oil. To paraphrase Nietzsche, the truth may be good, but why not sometimes take untruth if it gets you where you want to go?

These are important questions. At the end of the day, is it always better to believe and speak the truth? Does the truth itself really matter? While generalizing is always dangerous, the above responses to the Iraq affair indicate that many Americans would look at such questions with a jaundiced eye. We are rather cynical about the value of truth.

Politics isn't the only place that one finds this sort of skepticism. A similar attitude is commonplace among some of our most prominent intellectuals. Indeed, under the banner of postmodernism, cynicism about truth and related notions like objectivity and knowledge has become the semiofficial philosophical stance of many academic disciplines. Roughly speaking, the attitude is that objective truth is an illusion and what we call truth is just another name for power. Consequently, if truth is valuable at all, it is valuable -- as power is -- merely as means.

Stanley Fish, a prominent literary critic and former dean, cranked up the anti-truth rhetoric even further in an article last year, "Truth but No Consequences: Why Philosophy Doesn't Matter." Not only is objective truth an illusion, according to Fish, but even worrying about the nature of truth in the first place is a waste of time. Debating an abstract idea like truth is like debating whether Ted Williams was a better pure hitter than Hank Aaron: amusing, but irrelevant to today's game.

Sure, we may say we want to believe the truth, but what we really desire is to believe what is useful. Good beliefs get us what we want, whether nicer suits, bigger tax cuts, or a steady source of oil for our SUV's. At the end of the day, the truth of what we believe and say is beside the point. What matters are the consequences.

Such rough-and-ready pragmatism taps into one of our deepest intellectual veins. It appeals to America's collective self-image as a square-jawed action hero. And it may partly explain why the outcry against the White House's deception over the war in Iraq was rather muted. It is not just that we believe that "united we stand," it is that, deep down, many Americans are prone to think that it is results, not principles, that matter. Like Fish and Bush, some of us find worrying over abstract principles like truth to be boring and irrelevant nitpicking, best left to the nerds who watch C-Span and worry about whether the death penalty is "fair."

Of course, many intellectuals are eager to defend the idea that truth matters. Unfortunately, however, some of the defenses just end up undermining the value of truth in a different way. There is a tendency for some to believe, for example, that caring about truth means caring about the absolutely certain truths of old. That has always been a familiar tune on the right, whistled with fervor by writers like Allan Bloom and Robert H. Bork, but its volume has appeared to increase since September 11, 2001. Americans have lost their "moral compass" and need to sharpen their vision with "moral clarity," we are told. Liberal-inspired relativism is weakening American resolve; in order to prevail (against terrorism, the assault on family values, and the like) we must rediscover our God-given access to the truth. And that truth, it seems, is that we are right, and everyone else is wrong.

William J. Bennett, for example, in his book last year, Why We Fight: Moral Clarity and the War on Terrorism, laments the profusion of what he calls "an easygoing" relativism. Longing for the days when children were instructed to appreciate the "superior goodness of the American way of life," he writes: "If the message was sometimes overdone, or sometimes sugarcoated, it was a message backed by the record of history and by the evidence of even a child's senses." In the halcyon days of old, when the relativists had yet to scale the garden wall, the truth was so clear that it could be grasped by even a child. That is the sort of truth Bennett seems to think really matters. To care about objective truth is to care about what is simple and ideologically certain.

As a defense of the value of truth, that is self-defeating. An unswerving allegiance to what you believe isn't a sign that you care about truth. It is a sign of dogmatism. Caring about truth does not mean never having to admit you are wrong. On the contrary, caring about truth means that you have to be open to the possibility that your own beliefs are mistaken. It is a consequence of the very idea of objective truth. True beliefs are those that portray the world as it is and not as we hope, fear, or wish it to be. If truth is objective, believing doesn't make it so; and even our most deeply felt opinions could turn out to be wrong. That is something that Bennett -- and the current administration, for that matter -- would do well to remember. It is not a virtue to hold fast to one's views in face of the facts.

Thus some writers, like Fish, say that since faith in the absolute certainties of old is naïve, truth is without value. Others, like Bennett, argue that since truth has value, we had better get busy rememorizing its ancient dogmas. But the implicit assumption of both views is that the only truth worth valuing is Absolute Certain Truth. That is a mistake. We needn't dress truth up with capital letters to make it worth wanting; plain unadorned truth is valuable enough.

Like most left-leaning intellectuals who attended graduate school in the '90s, I have certainly had my own fling with cynicism about truth. I've played the postmodern; I've sympathized -- at length in my previous work -- with relativism. Disgusted by the right's lust for absolutes, many of us retreated from talk of objective truth and embraced the philosopher Richard Rorty's call for an "ironic" stance toward our own liberal sympathies. We stopped caring about whether we were "right" and thought more about what makes the world go round. That made us feel at once more hip and less naïve.

The events of the last three years have put the lie to that strategy. The fact that our government has deceived us, misled the nation into war, and passed legislation that threatens to infringe upon our basic human rights doesn't call for ironic detachment. It calls for outrage. But it is hard to justify outrage if your basic intellectual commitments suggest that everything is "just text" -- merely a story that could be retold in myriad ways. It is hard to stand up and fight for a political position that refuses to see itself as any better than any other.

So Stanley Fish couldn't be more wrong. Cynicism about truth is confused. And philosophical debates over truth matter because truth and its pursuit are politically important.

There are three simple reasons to think that truth is politically valuable. The first concerns the very point of even having the concept. At root, we distinguish truth from falsity because we need a way of distinguishing right answers from wrong ones. In particular, and as the debacle over weapons of mass destruction in Iraq clearly illustrates, we need a way of distinguishing between beliefs for which we have some partial evidence, or that are widely accepted by the community, or that fit our political ambitions, and those that actually end up being right.

It is not that we can't evaluate beliefs in all those other ways -- of course we can. But the other sorts of evaluation depend for their force on the distinction between truth and falsity. We think it is good to have some evidence for our views because we think that beliefs that are based on evidence are more likely to be true. We criticize people who engage in wishful thinking because wishful thinking often leads to believing falsehoods. In short, the primary point of having a concept of truth is that we need a basic norm for appraising and evaluating our beliefs and claims about the world. We need a way of sorting beliefs and assertions into those that are correct (or at least heading in that direction) and those that are incorrect.

Now imagine a society in which everyone believes that what makes an opinion true is whether it is held by those in power. So if the authorities say that black people are inferior to white people, or love is hate, or war is peace, then the citizens sincerely believe that is true. Such a society lacks something, to say the least. In particular, its people misunderstand truth, and the nature of their misunderstanding undermines the very point of even having the concept. Social criticism often involves expressing disagreement with those in power -- saying that their views on some matter are mistaken. But a member of our little society doesn't believe that the authorities can be mistaken. In order to believe that, they would have to be able to think that what the authorities say is incorrect. But their understanding of what correctness is rules out such a possibility. So criticism -- disagreement with those in power -- is, practically speaking, impossible.

Recently there has been a revival of interest in George Orwell's 1984. But discussions of the book often miss the point. The most terrifying aspect of Orwell's Ministry of Truth isn't its ability to get people to keep people from speaking their minds, or even to believe lies; it is its success at getting them to give up on the idea of truth altogether. When, at the end of the novel, O'Brien, the sinister representative of Big Brother, tortures the hapless Winston into believing that two and two make five, his point, as he makes brutally clear, is that Winston must "relearn" that whatever the party says is the truth. O'Brien doesn't really care about Winston's views on addition. What he cares about is getting rid of Winston's idea of truth. He is well aware of the point I've just been making. Eliminate the very idea of right and wrong independent of what the government says, and you eliminate not just dissent -- you eliminate the very possibility of dissent.

That is the first reason truth has political value. Just having the concept of objective truth opens up a certain possibility: It allows us to think that something might be correct even if those in power disagree. Without it, we wouldn't be able to distinguish between what those in power say is the case and what is the case.

The second reason truth is politically important is that one of our society's most basic political concepts -- that of a fundamental right -- presupposes the idea of objective truth. A fundamental right is different from a right that is granted merely as a matter of social policy. Policy rights -- such as the right of a police officer to carry a concealed weapon -- are justified because they are means to a worthwhile social goal, like public safety. Fundamental rights, on the other hand, are a matter of principle, as the philosopher Ronald Dworkin has famously put it in a book by that title. They aren't justified because they are a means to valuable social goals; fundamental rights are justified because they are a necessary component of basic respect due to all people. Fundamental rights, therefore, override other political concerns. You can't justifiably lose your right to privacy, for example, just because the attorney general suddenly decides we would all be less vulnerable to terrorism if the government knew what everyone was reading, buying, and saying. The whole point of having a fundamental or, as it is often put, "human right," is that it can't justifiably be taken away just because a government suddenly decides it would be in our interest to do so.

It follows that a necessary condition for fundamental rights is a distinction between what the government -- in the wide sense of the term -- says is so and what is true. That is, in order for me to understand that I have fundamental rights, it must be possible for me to have the following thought: that even though everyone else in my community thinks that, for example, same-sex marriages should be outlawed, people of the same sex still have a right to be married. But I couldn't have that thought unless I was able to entertain the idea that believing doesn't make things so, that there is something that my thoughts can respond to other than the views of my fellow citizens, powerful or not. The very concept of a fundamental right presupposes the concept of truth. Take-home lesson: If you care about your rights, you had better care about truth.

The conceptual connection between truth and rights reveals the third and most obvious reason truth has political value. It is vital that a government tell its citizens the truth -- whether it be about Iraq's capacities for producing weapons of mass destruction or high-ranking officials' ties to corporate interests. That is because governmental transparency and freedom of information are the first defenses against tyranny. The less a government feels the need to be truthful, the more prone it is to try and get away with doing what wouldn't be approved by its citizens in the light of day, whether that means breaking into the Watergate Hotel, bombing Cambodia, or authorizing the use of torture on prisoners. Even when they don't affect us directly, secret actions like those indirectly damage the integrity of our democracy. What you don't know can hurt you.

The late British philosopher Bernard Williams thought that point was too obvious to be of much use: "Tyrants will not be impressed by the argument and their victims do not need to be impressed," he wrote in 2002. But whether or not every Oxford don knows why governmental transparency is important, not everyone in Tupelo, Miss., or Greenwich, Conn., has heard the news. By only supplying two possible choices, tyrants and their victims, Williams artificially limited the options. For while the anti-tyranny argument may not be important for everyone -- no argument ever is -- it is important for anyone worried about the integrity of liberal democracy.

In particular, it is important for anyone who is looking for a rational platform on which to criticize a democratic government's lack of truthfulness on a particular issue. As Williams pointed out, such a rational platform won't be of interest to tyrants. And those already suffering under tyranny need more than rational platforms. But the anti-tyranny argument will be of interest to those whose government is not yet tyrannical, but who fear it is heading in that direction. In brief, the anti-tyranny argument is precisely the sort of argument that is of interest to concerned citizens of a liberal democracy like our own. Unless the government strives to tell the truth, liberal democracies are no longer liberal or democratic.

Perhaps that is a truism. But not all truisms are mere words mouthed in empty ritual. In the political arena, it is all too easy to choose expediency over principle. Thus sometimes truisms, while acting as rational platforms on which to criticize our government, also act as reminders. They warn us of what we have to lose. As the philosopher and social critic Michel Foucault aptly noted in an interview in 1984, unless it would impose "the silence of slavery," no government can afford to ignore its obligation to the truth.

Neither can intellectuals. By abandoning notions like truth and objectivity, many of us in the academy have forgotten the political value of those concepts. In part, that is because we've fallen into the simple-minded confusions I've discussed here. It is ironic that, in capitulating to many of the assumptions and labels of our conservative critics, we have conflated the pursuit of truth with the pursuit of dogma, pluralism with nihilism, openness to new ideas with detachment toward our own. We need to think our own way past such confusions and shed the cynicism about truth to which they give rise. If we don't, we risk imposing enslaving silence on ourselves. We risk losing our ability to speak truth to power.

Michael P. Lynch is an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Connecticut. This essay is adapted from his book True to Life: Why Truth Matters, to be published next month by the MIT Press.

Copyright © 2004 by The Chronicle of Higher Education