The Dickster (when he's not shooting quail-hunting cronies) and The Rumster long for the good old days. Like Neo-Nazis who long for a new Führer, these evil twins long for a return to the Imperial Presidency of RMN (The Trickster) before bad ol' Jimmy Carter put a clamp on untrammeled wiretaps. Dub wouldn't know a credible terrorist threat from My Pet Goat. Where's Barbara Jordan when we need her? Will Dub's Court appointees step up when the inevitable challenge to these unlawful wiretaps lands on their docket? If this is a (fair & balanced) impeachable offense, so be it.

[x Slate]

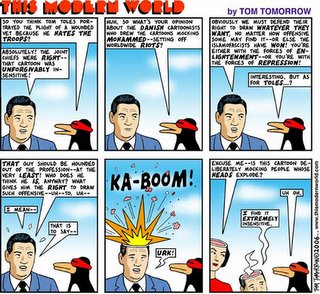

The Nixon Doctrine: If the commander in chief does it, it's not illegal.

By David Cole

President Bush's defense of his order authorizing the National Security Agency to spy on Americans without a warrant ultimately rests on a claim that Congress may not constitutionally limit the president's authority, as commander in chief, to select the "means and methods of engaging the enemy." This argument holds not only that the president has "inherent" power to collect "signals intelligence" on the enemy, but also that that his inherent power cannot be regulated or checked by Congress—even when it includes wiretapping Americans in the United States without a warrant.

This claim of uncheckable or "exclusive" constitutional authority amounts to nothing less than a modified version of President Nixon's infamous 1977 assertion that "when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal." President Bush has revived that discredited doctrine, with only a slight modification. His new formulation: If the commander in chief does it, it is not illegal. This unprecedented assertion cannot be squared with our constitutional structure, which relies upon checks and balances—even during wartime—or with Supreme Court precedent. Indeed, the Supreme Court rejected this precise claim when President Bush's lawyers made it in the Guantanamo detainees' case, Rasul v. Bush, in 2004. The administration, in short, is advancing a conception of presidential power that finds no support in constitutional precedent: the power to act above the law.

The president's argument, articulated in a 42-page single-spaced memorandum submitted to Congress, is that the commander in chief has inherent power to select the "means and methods of engaging the enemy." That power may not be restricted by Congress, the memo reasons. And since electronic surveillance related to al-Qaida falls within "engaging the enemy," the president cannot therefore be restricted in his decision to conduct such surveillance. Detention and interrogation are also "means and methods of engaging the enemy," so it would follow that any congressional effort to regulate these matters is also unconstitutional.

The argument is nothing if not bold. But accepting it would require overturning or ignoring the Supreme Court's decision in Rasul v. Bush. In arguing that case, the Bush administration made precisely the same contention it makes now. It maintained that interpreting the habeas corpus statute to extend to enemy combatants held at Guantanamo "would directly interfere with the Executive's conduct of the military campaign against al Qaeda and its supporters," and would therefore raise "grave constitutional problems." Rejecting this argument, the court ruled that Congress gave federal courts the power to hear these cases. Even Justice Antonin Scalia, who dissented, agreed that Congress could have extended habeas jurisdiction to the Guantanamo detainees. Thus, not one member of the Supreme Court accepted the president's commander-in-chief argument.

The Bush administration's defenders often protest that even if his NSA spying program does violate a criminal statute, the program is not necessarily illegal because a statute cannot override the Constitution. If the president could engage in foreign intelligence surveillance before Congress regulated that conduct through the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, they argue, Congress cannot constitutionally limit his ability to do it thereafter. They point to the fact that before FISA, presidents routinely conducted foreign intelligence surveillance, that courts recognized the legitimacy of that authority, and that the Clinton administration itself asserted the president's inherent authority to conduct physical searches for foreign intelligence purposes before FISA regulated such searches.

But this argument reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of separation of powers doctrine. That doctrine holds that the president's power to act is directly affected by actions taken by Congress. As Justice Robert Jackson explained in his influential concurring opinion in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, a 1952 case invalidating President Truman's seizure of steel mills during the Korean War, under our system of checks and balances, Congress' actions are critical. When Congress has affirmed the president's authority or remained silent, the president's "inherent" powers to take initiative are fairly broad; but when Congress has passed a law expressly barring the president's actions, he may act in contravention of that statute only if Congress is disabled from acting upon the subject. Accordingly, what presidents did before FISA was enacted, or what President Clinton did before FISA applied to physical searches, does not determine what the president may do once FISA criminally prohibits electronic surveillance and physical searches without a warrant.

Congress plainly is not "disabled from acting" on the subject of wiretapping of Americans. It has legislated in this area for years, and its authority to do so stems directly from its authority over interstate and foreign commerce. Moreover, the Constitution gives Congress widespread authority to regulate the commander in chief's conduct of a war. Congress defines the scope of the war under its power to declare war; it decides whether there shall be an army and how much it should be funded; and it creates rules and regulations for the army. It has long subjected the commander in chief to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, enacted statutes regarding the governance of occupied territories, enacted a habeas corpus statute that governs enemy combatant detainees, and prohibited torture, among other things. On the administration's theory of an uncheckable commander in chief, all these laws would also be unconstitutional.

Each time the Supreme Court has confronted a presidential claim that the commander in chief can act contrary to statute, or cannot be checked by the other branches, it has rejected it. In addition to the Guantanamo and steel-seizure cases mentioned above, the court in Little v. Barreme, an 1804 decision, ruled unlawful a presidentially authorized seizure of a ship during the "Quasi War" with France. The court found Congress had authorized the seizure only of ships going to France, and therefore the president could not unilaterally order the seizure of a ship coming from France.

And in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, the court expressly rejected the president's argument that courts may not inquire into the factual basis for the detention of a U.S. citizen as an enemy combatant. As Justice O'Connor wrote for the plurality, "Whatever power the United States Constitution envisions for the Executive in its exchanges with other nations or with enemy organizations in times of conflict, it most assuredly envisions a role for all three branches when individual liberties are at stake."

The fact that the Supreme Court has never found a commander-in-chief function that could not be regulated by Congress does not mean, of course, that there are no limits on Congress' power. If Congress sought to micromanage the war by assigning authority to lead the troops to someone outside the president's chain of command and subject to congressional removal, for example, its actions would likely be unconstitutional. But the notion that Congress cannot protect the privacy of Americans during wartime by requiring the president to obtain a warrant before spying on Americans is entirely unprecedented—unless, that is, you consider the bare assertions of Richard Nixon a precedent.

David Cole is a professor at Georgetown University Law Center and pro bono co-counsel in Center for Constitutional Rights v. Bush, which challenges the legality of the NSA program.

Copyright © 2006 Slate

Get an RSS (Really Simple Syndication) Reader at no cost from Google at Google Reader. Another free Reader is available at RSS Reader.