Joseph Epstein, former editor of The American Scholar, is witty and erudite. Here, he analyzes the end times of print journalism. Thanks to the Internet, I receive the NYTimes, the Washington Post, and the LATimes daily in my e-mail In Box. I can customize my online subscriptions to include only the sections of each paper that interest me. My issues omit Home & Living, Financial News, and such fluff (to my taste). How can the newspapers give all of this away for nothing? I cannot remember clicking on a single banner ad in any of the e-mail versions I receive. No wonder newspapers are in financial difficulty. If this is (fair & balanced) pessimism, so be it.

[x Commentary]

Are Newspapers Doomed?

By Joseph Epstein

“Clearly,” said Adam to Eve as they departed the Garden of Eden, “we’re living in an age of transition.” A joke, of course—but also not quite a joke, because when has the history of the world been anything other than one damned transition after another? Yet sometimes, in certain realms, transitions seem to stand out with utter distinctiveness, and this seems to be the case with the fortune of printed newspapers at the present moment. As a medium and as an institution, the newspaper is going through an age of transition in excelsis, and nobody can confidently say how it will end or what will come next.

To begin with familiar facts, statistics on readership have been pointing downward, significantly downward, for some time now. Four-fifths of Americans once read newspapers; today, apparently fewer than half do. Among adults, in the decade 1990-2000, daily readership fell from 52.6 percent to 37.5 percent. Among the young, things are much worse: in one study, only 19 percent of those between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four reported consulting a daily paper, and only 9 percent trusted the information purveyed there; a mere 8 percent found newspapers helpful, while 4 percent thought them entertaining.

From 1999 to 2004, according to the Newspaper Association of America, general circulation dropped by another 1.3 million. Reflecting both that fact and the ferocious competition for classified ads from free online bulletin boards like craigslist.org, advertising revenue has been stagnant at best, while printing and productions costs have gone remorselessly upward. As a result, the New York Times Company has cut some 700 jobs from its various papers. The Baltimore Sun, owned by the Chicago Tribune, is closing down its five international bureaus. Second papers in many cities have locked their doors.

This bleeding phenomenon is not restricted to the United States, and no bets should be placed on the likely success of steps taken by papers to stanch the flow. The Wall Street Journal, in an effort to save money on production costs, is trimming the width of its pages, from 15 to 12 inches. In England, the once venerable Guardian, in a mad scramble to retain its older readers and find younger ones, has radically redesigned itself by becoming smaller. London’s Independent has gone tabloid, and so has the once revered Times, its publisher preferring the euphemism “compact.”

For those of us who grew up with newspapers in our daily regimen, sometimes with not one but two newspapers in our homes, it is all a bit difficult to take in. As early as 1831, Alexis de Tocqueville noted that even frontier families in upper Michigan had a weekly paper delivered. A.J. Liebling, the New Yorker’s writer on the press, used to say that he judged any new city he visited by the taste of its water and the quality of its newspapers.

The paper to which you subscribed, or that your father brought home from work, told a good deal about your family: its social class, its level of education, its politics. Among the five major dailies in the Chicago of my early boyhood, my father preferred the Daily News, an afternoon paper reputed to have excellent foreign correspondents. Democratic in its general political affiliation, though not aggressively so, the Daily News was considered the intelligent Chicagoan’s paper.

My father certainly took it seriously. I remember asking him in 1952, as a boy of fifteen, about whom he intended to vote for in the presidential election between Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson. “I’m not sure,” he said. “I think I’ll wait to see which way Lippmann is going.”

The degree of respect then accorded the syndicated columnist Walter Lippmann is hard to imagine in our own time. In good part, his cachet derived from his readers’ belief not only in his intelligence but in his impartiality. Lippmann, it was thought, cared about what was best for the country; he wasn’t already lined up; you couldn’t be certain which way he would go.

Of the two candidates in 1952, Stevenson, the intellectually cultivated Democrat, was without a doubt the man Lippmann would have preferred to have lunch with. But in the end he went for Eisenhower—his reason being, as I recall, that the country needed a strong leader with a large majority behind him, a man who, among other things, could face down the obstreperous Red-baiting of Senator Joseph McCarthy. My father, a lifelong Democrat, followed Lippmann and crossed over to vote for Eisenhower.

My father took his paper seriously in another way, too. He read it after dinner and ingested it, like that dinner, slowly, treating it as a kind of second dessert: something at once nutritive and entertaining. He was in no great hurry to finish.

Today, his son reads no Chicago newspaper whatsoever. A serial killer could be living in my apartment building, and I would be unaware of it until informed by my neighbors. As for the power of the press to shape and even change my mind, I am in the condition of George Santayana, who wrote to his sister in 1915 that he was too old to “be influenced by newspaper argument. When I read them I form perhaps a new opinion of the newspaper but seldom a new opinion on the subject discussed.”

I do subscribe to the New York Times, which I read without a scintilla of glee. I feel I need it, chiefly to discover who in my cultural world has died, or been honored (probably unjustly), or has turned out some new piece of work that I ought to be aware of. I rarely give the daily Times more than a half-hour, if that. I begin with the obituaries. Next, I check the op-ed page, mostly to see if anyone has hit upon a novel way of denigrating President Bush; the answer is invariably no, though they seem never to tire of trying. I glimpse the letters to the editor in hopes of finding someone after my own heart. I almost never read the editorials, following the advice of the journalist Jack Germond who once compared the writing of a newspaper editorial to wetting oneself in a dark-blue serge suit: “It gives you a nice warm feeling, but nobody notices.”

The arts section, which in the Times is increasingly less about the arts and more about television, rock ’n’ roll, and celebrity, does not detain me long. Sports is another matter, for I do have the sports disease in a chronic and soon to be terminal stage; I run my eyes over these pages, turning in spring, summer, and fall to see who is pitching in that day’s Cubs and White Sox games. And I always check the business section, where some of the better writing in the Times appears and where the reporting, because so much is at stake, tends to be more trustworthy.

Finally—quickly, very quickly—I run through the so-called hard news, taking in most of it at the headline level. I seem able to sleep perfectly soundly these days without knowing the names of the current presidents or prime ministers of Peru, India, Japan, and Poland. For the rest, the point of view that permeates the news coverage in the Times is by now so yawningly predictable that I spare myself the effort of absorbing the facts that seem to serve as so much tedious filler.

Am I typical in my casual disregard? I suspect so. Everyone agrees that print newspapers are in trouble today, and almost everyone agrees on the reasons. Foremost among them is the vast improvement in the technology of delivering information, which has combined in lethal ways with a serious change in the national temperament.

The technological change has to do with the increase in the number of television cable channels and the astonishing amount of news floating around in cyberspace. As Richard A. Posner has written, “The public’s consumption of news and opinion used to be like sucking on a straw; now it’s like being sprayed by a fire hose.”

The temperamental change has to do with the national attention span. The critic Walter Benjamin said, as long ago as the 1930’s, that the chief emotion generated by reading the newspapers is impatience. His remark is all the more pertinent today, when the very definition of what constitutes important information is up for grabs. More and more, in a shift that cuts across age, social class, and even educational lines, important information means information that matters to me, now.

And this is where the two changes intersect. Not only are we acquiring our information from new places but we are taking it pretty much on our own terms. The magazine Wired recently defined the word “egocasting” as “the consumption of on-demand music, movies, television, and other media that cater to individual and not mass-market tastes.” The news, too, is now getting to be on-demand.

Instead of beginning their day with coffee and the newspaper, there to read what editors have selected for their enlightenment, people, and young people in particular, wait for a free moment to go online. No longer need they wade through thickets of stories and features of no interest to them, and least of all need they do so on the websites of newspapers, where the owners are hoping to regain the readers lost to print. Instead, they go to more specialized purveyors of information, including instant-messaging providers, targeted news sites, blogs, and online “zines.”

Much cogitation has been devoted to the question of young people’s lack of interest in traditional news. According to one theory, which is by now an entrenched cliché, the young, having grown up with television and computers as their constant companions, are “visual-minded,” and hence averse to print. Another theory holds that young people do not feel themselves implicated in the larger world; for them, news of that world isn’t where the action is. A more flattering corollary of this is that grown-up journalism strikes the young as hopelessly out of date. All that solemn good-guy/bad-guy reporting, the taking seriously of opéra-bouffe characters like Jesse Jackson or Al Gore or Tom DeLay, the false complexity of “in-depth” television reporting à la 60 Minutes—this, for them, is so much hot air. They prefer to watch Jon Stewart’s "The Daily Show" on the Comedy Central cable channel, where traditional news is mocked and pilloried as obvious nonsense.

Whatever the validity of this theorizing, it is also beside the point. For as the grim statistics confirm, the young are hardly alone in turning away from newspapers. Nor are they alone responsible for the dizzying growth of the so-called blogosphere, said to be increasing by 70,000 sites a day (according to the search portal technorati.com). In the first half of this year alone, the number of new blogs grew from 7.8 to 14.2 million. And if the numbers are dizzying, the sheer amount of information floating around is enough to give a person a serious case of Newsheimers.

Astonishing results are reported when news is passed from one blog to another: scores if not hundreds of thousands of hits, and, on sites that post readers’ reactions, responses that can often be more impressive in research and reasoning than anything likely to turn up in print. Newspaper journalists themselves often get their stories from blogs, and bloggers have been extremely useful in verifying or refuting the erroneous reportage of mainstream journalists. The only place to get a reasonably straight account of news about Israel and the Palestinians, according to Stephanie Gutmann, author of The Other War: Israelis, Palestinians, and the Struggle for Media Supremacy, is in the blogosphere.

The trouble with blogs and Internet news sites, it has been said, is that they merely reinforce the reader’s already established interests and views, thereby contributing to our much-lamented national polarization of opinion. A newspaper, by contrast, at least compels one to acknowledge the existence of other subjects and issues, and reading it can alert one to affecting or important matters that one would never encounter if left to one’s own devices, and in particular to that primary device of our day, the computer. Whether or not that is so, the argument has already been won, and not by the papers.

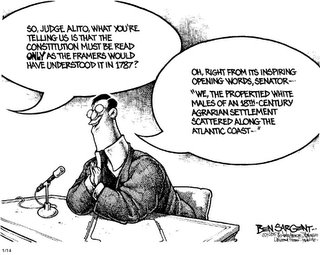

Another argument appears to have been won, too, and again to the detriment of the papers. This is the argument over politics, which the newspapers brought upon themselves and which, in my view, they richly deserved to lose.

One could put together an impressive little anthology of utterances by famous Americans on the transcendent importance of the press as a guardian watchdog of the state. Perhaps the most emphatic was that of Thomas Jefferson, who held that freedom of the press, right up there with freedom of religion and freedom of the person under the rights of habeas corpus and trial by jury, was among “the principles [that] form the bright constellation which has gone before us, and guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation.” Even today, not many people would disagree with this in theory; but like the character in a Tom Stoppard play, many would add: “I’m with you on the free press. It’s the damned newspapers I can’t stand.”

The self-proclaimed goal of newsmen used to be to report, in a clear and factual way, on the important events of the day, on subjects of greater or lesser parochialism. It is no longer so. Here is Dan Rather, quoting with approval someone he does not name who defines news as “what somebody doesn’t want you to know. All the rest is advertising.”

“What somebody doesn’t want you to know”—it would be hard to come up with a more concise definition of the target of the “investigative journalism” that has been the pride of the nation’s newspapers for the past three decades. Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein, Seymour Hersh, and many others have built their reputations on telling us things that Presidents and Senators and generals and CEO’s have not wanted us to know.

Besides making for a strictly adversarial relationship between government and the press, there is no denying that investigative journalism, whatever (very mixed) accomplishments it can claim to its credit, has put in place among us a tone and temper of agitation and paranoia. Every day, we are asked to regard the people we elect to office as, essentially, our enemies—thieves, thugs, and megalomaniacs whose vicious secret deeds it is the chief function of the press to uncover and whose persons to bring down in a glare of publicity.

All this might have been to the good if what the journalists discovered were invariably true—and if the nature and the implications of that truth were left for others to puzzle out. Frequently, neither has been the case.

Much of contemporary journalism functions through leaks—information passed to journalists by unidentified individuals telling those things that someone supposedly doesn’t want us to know. Since these sources cannot be checked or cross-examined, readers are in no position to assess the leakers’ motives for leaking, let alone the agenda of the journalists who rely on them. To state the obvious: a journalist fervently against the U.S. presence in Iraq is unlikely to pursue leaks providing evidence that the war has been going reasonably well.

Administrations have of course used leaks for their own purposes, and leaks have also become a time-tested method for playing out intramural government disputes. Thus, it is widely and no doubt correctly believed that forces at the CIA and in the State Department have leaked information to the New York Times and the Washington Post to weaken positions taken by the White House they serve, thereby availing themselves of a mechanism of sabotage from within. But this, too, is not part of the truth we are likely to learn from investigative journalists, who not only purvey slanted information as if it were simply true but then take it upon themselves to try, judge, and condemn those they have designated as political enemies. So glaring has this problem become that the Times, beginning in June, felt compelled to introduce a new policy, designed, in the words of its ombudsman, to make “the use of anonymous sources the ‘exception’ rather than ‘routine.’”

No wonder, then, that the prestige of mainstream journalism, which reached perhaps an all-time high in the early 1970’s at the time of Watergate, has now badly slipped. According to most studies of the question, journalists tend more and more to be regarded by Americans as unaccountable kibitzers whose self-appointed job is to spread dissension, increase pressure on everyone, make trouble—and preach the gospel of present-day liberalism. Aiding this deserved fall in reputation has been a series of well-publicized scandals like the rise and fall of the reporter Jayson Blair at the New York Times.

The politicization of contemporary journalists surely has a lot to do with the fact that almost all of them today are university-trained. In Newspaper Days, H.L. Mencken recounts that in 1898, at the age of eighteen, he had a choice of going to college, there to be taught by German professors and on weekends to sit in a raccoon coat watching football games, or of getting a job on a newspaper, which would allow him to zip off to fires, whorehouse raids, executions, and other such festivities. As Mencken observes, it was no contest.

Most contemporary journalists, by contrast, attend schools of journalism or study the humanities and social sciences. Here the reigning politics are liberal, and along with their degrees, and their sense of enlightened virtue, they emerge with locked-in political views. According to Jim A. Kuypers in Press Bias and Politics, 76 percent of journalists who admit to having a politics describe themselves as liberal. The consequences are predictable: even as they employ their politics to tilt their stories, such journalists sincerely believe they are (a) merely telling the truth and (b) doing good in the world.

Pre-university-educated journalists did not, I suspect, feel that the papers they worked for existed as vehicles through which to advance their own political ideas. Some among them might have hated corruption, or the standard lies told by politicians; from time to time they might even have felt a stab of idealism or sentimentality. But they subsisted chiefly on cynicism, heavy boozing, and an admiration for craft. They did not treat the news—and editors of that day would not have permitted them to treat the news—as a trampoline off which to bounce their own tendentious politics.

To the degree that papers like the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times have contributed to the political polarization of the country, they much deserve their fate of being taken less and less seriously by fewer and fewer people. One can say this even while acknowledging that the cure, in the form of on-demand news, can sometimes seem as bad as the disease, tending often only to confirm users, whether liberal or conservative or anything else, in the opinions they already hold. But at least the curious or the bored can, at a click, turn elsewhere on the Internet for variety or relief—which is more than can be said for newspaper readers.

Nor, in a dumbed-down world, do our papers of record offer an oasis of taste. There were always a large number of newspapers in America whose sole standard was scandal and entertainment. (The crossword puzzle first appeared in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.) But there were also some that were dedicated to bringing their readers up to a high or at least a middling mark. Among these were the New York Times, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the Washington Post, the Milwaukee Journal, the Wall Street Journal, the now long defunct New York Herald-Tribune, and the Chicago Daily News.

These newspapers did not mind telling readers what they felt they ought to know, even at the risk of boring the pajamas off them. The Times, for instance, used to run the full text of important political speeches, which could sometimes fill two full pages of photograph-less type. But now that the college-educated are writing for the college-educated, neither party seems to care. And with circulation numbers dwindling and the strategy in place of whoring after the uninterested young, anything goes.

What used to be considered the serious press in America has become increasingly frivolous. The scandal-and-entertainment aspect more and more replaces what once used to be called “hard news.” In this, the serious papers would seem to be imitating the one undisputed print success of recent decades, USA Today, whose guiding principle has been to make things brief, fast-paced, and entertaining. Or, more hopelessly still, they are imitating television talk shows or the Internet itself, often mindlessly copying some of their dopier and more destructive innovations.

The editor of the London Independent has talked of creating, in place of a newspaper, a “viewspaper,” one that can be viewed like a television or a computer. The Los Angeles Times has made efforts to turn itself interactive, including by allowing website readers to change the paper’s editorials to reflect their own views (only to give up on this initiative when readers posted pornography on the page). In his technology column for the New York Times, David Carr speaks of newspapers needing “a podcast moment,” by which I take him to mean that the printed press must come up with a self-selecting format for presenting on-demand news akin to the way the iPod presents a listener’s favorite programming exactly as and when he wants it.

In our multitasking nation, we already read during television commercials, talk on the cell-phone while driving, listen to music while working on the computer, and much else besides. Some in the press seem in their panic to think that the worst problem they face is that you cannot do other things while reading a newspaper except smoke, which in most places is outlawed anyway. Their problems go much deeper.

In a speech given this past April to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, the international publisher Rupert Murdoch catalogued the drastic diminution of readership for the traditional press and then went on to rally the troops by telling them that they must do better. Not different, but better: going deeper in their coverage, listening more intently to the desires of their readers, assimilating and where possible imitating the digital culture so popular among the young. A man immensely successful and usually well anchored in reality, Murdoch here sounded distressingly like a man without a plan.

Not that I have one of my own. Best to study history, it is said, because the present is too complicated and no one knows anything about the future. The time of transition we are currently going through, with the interest in traditional newspapers beginning to fade and news on the computer still a vast confusion, can be likened to a great city banishing horses from its streets before anyone has yet perfected the automobile.

Nevertheless, if I had to prophesy, my guess would be that newspapers will hobble along, getting ever more desperate and ever more vulgar. More of them will attempt the complicated mental acrobatic of further dumbing down while straining to keep up, relentlessly exerting themselves to sustain the mighty cataract of inessential information that threatens to drown us all. Those of us who grew up with newspapers will continue to read them, with ever less trust and interest, while younger readers, soon enough grown into middle age, will ignore them.

My own preference would be for a few serious newspapers to take the high road: to smarten up instead of dumbing down, to honor the principles of integrity and impartiality in their coverage, and to become institutions that even those who disagreed with them would have to respect for the reasoned cogency of their editorial positions. I imagine such papers directed by editors who could choose for me—as neither the Internet nor I on my own can do—the serious issues, questions, and problems of the day and, with the aid of intelligence born of concern, give each the emphasis it deserves.

In all likelihood a newspaper taking this route would go under; but at least it would do so in a cloud of glory, guns blazing. And at least its loss would be a genuine subtraction. About our newspapers as they now stand, little more can be said in their favor than that they do not require batteries to operate, you can swat flies with them, and they can still be used to wrap fish.

Joseph Epstein contributed “Forgetting Edmund Wilson” to last month’s Commentary. His new book, Friendship, An Exposé, will be published by Houghton Mifflin in July.

Copyright © 2006 Commentary

Get an RSS (Really Simple Syndication) Reader at no cost from Google at Google Reader.

Get an RSS (Really Simple Syndication) Reader at no cost from Google at Google Reader.