Oh, yes. The tax freeze referendum in Georgetown, TX is producing tension. The proponents are largely found in Sun City. The opponents are largely found in Georgetown proper. Complaining about taxes is as American as apple pie. Demagogues from Samuel Adams to Howard Jarvis to George W. Bush have ridden tax protest to enormous success (and mischief, in many cases). Samuel Adams was a neer-do-well who attained status beyond his feverish dreams in the streets of Boston before 1776. Howard Jarvis was a consumer rights activist who led a campaign in California in 1978 for "Proposition 13" which cut property taxes by 57 percent. California has become a fiscal disaster since Prop 13. George W. Bush has pushed tax cuts through which will provide my grandchildren with crushing debt in 25 years. So, the sucessful use of tax cuts or tax freezes—while enormously popular now—will be disastrously costly in the future. Jacques Barzun (longtime provost of Columbia University and wiser than any tax protester in Sun City, TX) wrote that Taxes are the price we pay for a civilized society. If the City of Georgetown de-annexes Sun City, the tax protesters will find the price of fire and police protection is onerous indeed. If this is (fair & balanced) dissent, so be it.

[x Texas Monthly]

Up and Away

What happens when a small town becomes a big town, when its population grows and its economy takes off? Much is gained—but much is lost.

by Paul Burka

EVERY TEXAN HAS A FAVORITE small town. I would be hard-pressed to choose among Hunt, near Kerrville, where the forks of the Guadalupe join and I spent three summers as a camper and a counselor; Hallettsville, halfway between Houston and San Antonio on a forgotten highway, with its grand courthouse and square; and Fort Davis, which still manages to be quaint in the face of creeping chicness. But if I could take some liberties with the definition of "small," I would choose Georgetown, thirty miles north of Austin on Interstate 35, for the nobility of its struggle to remain a small town in the face of the economic and social trends of our time.

In 1890 Georgetown had around 2,400 people. It grew almost imperceptibly, taking six decades to double in population, to around 4,900, and another three decades to double again. Since that benchmark of 1980, though, its population has more than trebled, to an estimated 37,000, as the great metropolis that begins more than a hundred miles to the south in San Antonio has enfolded it.

What difference does the "small town" designation make? A big one, actually. The numerical battle between country and city was long ago decided in favor of the city: In 1900 more than 80 percent of Texans lived in or near small towns, but today more than 80 percent live in metropolitan areas, either in the city itself or close enough to fall under its influence. But the emotional battle still hangs in the balance. The farmer and the rancher moved to the city and the suburb, but they did not cease to be country folk. They still wear jeans and boots, still drive pickups, still prefer country music, still pine for the wide-open spaces when stuck in traffic—and so do their urban cousins who have never set foot on a farm or a ranch. Longtime readers of this magazine will recognize these as familiar themes, as fresh as last month's cover story on the pickup as the new national car of Texas. The state may be urban, but its soul remains rural.

This issue of Texas Monthly pays homage to that rural soul. Every article is set in a small town or touts the amenities offered by small towns—"small" being defined as a population of fewer than 15,000. So Georgetown doesn't qualify. But don't tell that to Georgetown, for nothing is so important to its residents as their desire that it remain a small town in its values.

This too is a familiar theme: The hold of the countryside on the Texas mind has more to do with roots than boots. It survives due to the persistence of the notion that the country way of life is better than the city way of life—and that something has been irretrievably lost in the process of urbanization. But moving away is only half of what has happened to small towns; the other half is moving to. As the countryside emptied out and the cities filled up, small towns on the urban fringe—which were once just dots on the map, no different from the places featured in this issue—became big towns. Places like Georgetown can tell us what was lost in the transition from country to city, from little to big.

From the highway, it has that could-be-anywhere-on-Interstate-America look. But if you venture into the old town site that was all there was of Georgetown until new subdivisions vaulted across the interstate in the seventies, the town's charm becomes apparent. It is a county seat, with a black-domed courthouse dating from the days when such buildings were designed to impress and a lively town square with a number of well-preserved nineteenth-century buildings. It's a college town too (home to Southwestern University, an upwardly mobile liberal arts school), though locals lament that it is less of a college town than it used to be. Two forks of the San Gabriel River run through Georgetown, their tree-lined channels crossing under the interstate. North of town, the metropolis comes to a surprising and sudden end, and you reenter rural Texas.

Virtually all of the growth has occurred west of the interstate, most notably in Sun City, a subdivision for seniors, where kids are allowed to visit but not move in. Around five thousand people live there, in one-story homes on ample lots that front gently curving streets. My wife's aunt and uncle, Elsie and Pat, moved there a year ago, and we drove up to meet them at a restaurant on the square.

"Georgetown is really a small town for us," Pat said. "Everybody is so nice. In Houston, the so-called help at the stores was so abusive. The last time I got my driver's license renewed, my photograph was the worst-looking thing I ever saw. I couldn't get it changed. The woman absolutely refused. Here, the lady told me, 'Smile. You want to look good on your driver's license.' Then she let me come behind the counter to be sure I liked the one she had taken."

The thing they like best about Georgetown is the square. After lunch, Elsie ushered us down the street to The Escape, a gift shop where almost everything in the store is made locally, and then to the Hill Country Bookstore. She mentioned the new mall, the town's first, that was recently approved by the city, to be located just west of the interstate near one of the east-west crossroads. "We're concerned about its impact on the square," Pat said. "We don't want to see these businesses disadvantaged."

The seniors contribute to the town. Elsie and Pat support the Palace Theatre, which long ago stopped showing movies regularly but puts on plays and concerts, and they plan to join the Symphony Society, which brings in the orchestra from Temple, 35 miles to the north, for concerts. And everybody in town talks about the Georgettes, an organization of Sun City women who were twirlers in their youth and strut their remaining stuff at high school football games. But there is also tension. A recent state law gives cities the power to freeze the property taxes of seniors, and a group of Sun City residents asked the city council to do just that. But the council resisted; seniors own 27 percent of the city's taxable property, which means that the people who own the remaining 73 percent would probably face a tax increase. The seniors organized a petition drive and forced an upcoming vote on the issue.

Sun City isn't the only reason that politics is a lot more intense than it used to be. Growth brings conflict. New schools create fights over boundary changes; as small as Georgetown is, nobody likes sending their kids across the interstate to school, in either direction. Different factions offer competing ideas about what Georgetown should be: a bedroom community for Austin? A competitor of nearby Round Rock, where Dell is based, for industry? A place that preserves its small-town feeling? Recent battles have been waged over a proposal for a large Walgreen's (it was defeated), a bond issue for a new library (likewise), and a restrictive design code (it passed, but only after the mayor, who irritated townspeople with her outspoken advocacy of the code, had been ousted by a recall vote).

"Everybody here used to have a sense of joint ownership of the town," Clark Thurmond, the publisher of the twice-weekly Williamson County Sun, told me, explaining the recall fight. "You could walk up to any city council member and say, 'Fix my street,' and it would get done. You'd know them and they'd know you. Your voice was heard. That tends to go away when a town gets big, but people here still expect it." Clark is married to Linda Scarbrough, whose family has owned the Sun since 1948 and whom I have known since we were at the University of Texas in the sixties. When I asked her what she missed from the Georgetown she knew when she was growing up, she mentioned two things: the river and the university.

"We've lost the river," she said. "It used to be easy to get to low-water crossings. We would throw rocks, collect fossils, wade, and fish. Traffic demands have just about shut off access. There are still parks and hiking trails, but the openness of the landscape is lost."

The other thing she misses is the involvement of the university in the town. On the way to dinner at a new restaurant called Wildfire—one of the advantages of size is that residents who want to go out for a good meal no longer have to go to Round Rock—we detoured by a public-housing project called Stonehaven that dates from the sixties. As Linda related the story, the city was going to build a typical low-budget project until a Southwestern professor named Bob Lancaster got involved, backed by Linda's father and the Sun. Almost forty years later, the attractive stone-and-wood units still look more like apartments than a housing project.

Linda remembers when most professors lived in Georgetown and sometimes served on the school board and the city council. But as the university has gotten more ambitious academically, town and gown have gone their separate ways. One of the complaints at Southwestern is that Georgetown is dry, so there is nowhere for the students to go in the evenings except Austin. "Southwestern has pulled themselves out of this community," a friend from Georgetown who works in Austin told me. He mentioned a now-departed president who "would have built walls and a moat around the school if he could."

Walls and a moat: Georgetown would love to do the same. It would love to keep out the metropolis (but keep the proximity to high-paying jobs), keep out the traffic (but keep the interstate), keep out the seniors, at least on Election Day (but keep their tax dollars), keep out the competition for the businesses on the square (but keep the convenience of the mall). The paradox of growth is that something is lost, but something is gained, and as much as people feel the loss, most are unwilling to sacrifice the gain. This is why small towns in the path of the metropolis ultimately become big towns. To Georgetown's great credit, that hasn't happened yet.

Paul Burka joined the staff of TEXAS MONTHLY one year after the magazine's founding. A lifelong Texan, he was born in Galveston, graduated from Rice University with a B.A. in history, and received a J.D. from the University of Texas School of Law.

Burka is a member of the State Bar of Texas and spent five years as an attorney with the Texas Legislature, where he served as counsel to the Senate Natural Resources Committee.

Burka won a National Magazine award for reporting excellence in 1985 and the American Bar Association’s Silver Gavel Award. He is a member of the Texas Institute of Letters and teaches at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. He is also a frequent guest discussing politics on national news programs on MSNBC, Fox, NBC, and CNN.

Copyright © 2004 Texas Monthly Magazine

Tuesday, August 31, 2004

Being A Geezer Can Be Very Taxing

The Next Governor Of Texas Will Hail From Medina!

Medina, TX is at the intersection of State Highway 16 and Farm Road 337, twelve miles northwest of Bandera in central Bandera County. It is home to Richard (Kinky) Friedman, next governor of Texas. The Kinkster's meditation is in keeping with the magazine's September theme of small towns in Texas. If this is (fair & balanced) pastoralism, so be it.

[x Texas Monthly]

Man About Town

by Richard (Kinky) Friedman

Why do I like living "in the middle of nowhere"? The dry cleaning's cheaper, I hear stories about snakes, I meet the most colorful characters on the planet, and I never get the urge to shoot the bird. (Well . . .)

IN 1985, AFTER THE DEATH of my mother, I left New York for good to seek shelter in the small towns that lay scattered about the Hill Country as if they were peppered by the hand of God onto the gravy of a chicken-fried steak. In New York people believe that nothing of importance ever happens outside the city, that if it doesn't occur inside their own office, it hasn't occurred at all. My friends told me that I would be a quitter if I gave up whatever the hell I was doing in New York and went back home. One of the things I was doing was large quantities of Peruvian marching powder, and I now believe that leaving may have saved my life.

I'd had, it seemed, seven years of bad luck. One of my two great loves, Kacey Cohen, had kissed a windshield at 95 miles per hour in her Ferrari. My other great love, of course, was me. My best friend, Tom Baker, troublemaker, had overdosed in New York. I'd come back to Austin just in time to spend a few months with my mother before she died. My dear Minnie, from whom much of my soul springs, left me with three cats, a typewriter, and a talking car. She wanted me to be in good company, to write, and to have somebody to talk to. The car's name was Dusty. She was a 1983 Chrysler LeBaron convertible with a large vocabulary, including the phrase "A door is ajar" (at this time of my life, one definitely was). My mother had always believed in me. Now, it seemed, it was time for me to believe in myself.

After New York, you'd think Austin would be a pleasant relief, but to my jangled mind there still seemed to be too many people. So I corralled Cuddles, Dr. Skat, and Lady into Dusty and together we drifted up to the Hill Country, where the people talk slow, the hills embrace you, and the small towns flash by like bright stations reflecting on the windows of a train at night. As Bob Dylan once wrote, "It takes a train to cry." As I once wrote, "Anything worth cryin' can be smiled."

What is it about small towns that always seems to be oddly comforting? Jesus was born in one. James Dean ran away from one. While visiting Italy, my father once said, "If you've seen one Sistine Chapel, you've seen them all." This is true of small towns as well, except they're not particularly good places to get postcards from. "Why would anyone want to live here?" somebody always says. "It's out in the middle of nowhere. It's so far away." And the gypsy answers, "From where?"

There is a fundamental difference between big-city and country folks. In the city you can honk at the traffic, shout epithets, and shoot the bird at anybody you like. You know you'll probably never see those people again. In a small town, however, you're responsible for your behavior. Instead of spouting off, you have to simply smile and shake your head. You know you're going to see the same people again in church, or maybe at a cross burning. (Just kidding.)

Another positive aspect of living in or near small towns is that they're breeding grounds for some of the most colorful characters on the planet. They're also good places to hear stories about snakes. Dry cleaning's cheaper than it is in the big city, and life itself perhaps is a bit more precious, always allowing for inflation. There is, of course, no dry cleaner's in Medina. You have to go to Bandera. And if you want to rent a good video, you probably should go to Kerrville. I say this because the Bandera video store has Kiss of the Spider Woman racked in the section with Friday the 13th and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Arguably Agatha Christie's greatest creation, Miss Marple, hailed from the small English town of St. Mary Mead. In a lifetime of fictional crime detection, the sage Miss Marple contended that the true character of people anywhere in the world could be easily divined by casting her mind back to the people she'd grown up with. For instance, the shy Peeping Tom in London reminded her keenly of the butcher's son in St. Mary Mead, who'd been slightly off-kilter but would never have harmed a flea. In such manner she determined that he was not the murderer of the fifth Duchess of Phlegm-on-Rye. In other words, the small town, like the small child, often dictates the emotional heritage of the human race. Unfortunately, because of shifting populations, even this great measure of mankind seems to be changing. When Tonto gets off his horse these days and puts his ear to the ground, he says to the Lone Ranger, "Kemosabe, thousands of yuppies are coming!"

So maybe there's not that much difference between small-town life and life in the big city. When I lived in New York, like most New Yorkers, I rarely ventured outside my own little neighborhood in the Village. I bought newspapers at the same stand every morning, frequented the same cigar shop near Sheridan Square, and hung out at a bar right across the avenue called the Monkey's Paw. Like most Manhattanites, I never went to Brooklyn, never visited the Statue of Liberty, never ascended to the top of the Empire State Building, and never took a ride on the Staten Island Ferry. That was all for the tourists, most of whom, ironically, were from small towns.

My old departed friend Earl Buckelew, the unofficial mayor of Medina, always used to say, "Everything comes out in the wash if you use enough Tide." Yet there are tides that run deep in small towns, deep as the sea of humanity, deep as the winding, muddy river of life. There once were two lovers who lived in Medina: Earl's youngest son, John, and his true love, the beautiful Janis. Though still in their teens, it is very possible that they shared a love many of us have forfeited, forgotten, or never known. A love of this kind can sometimes be incandescent in its innocence, reaching far beyond the time and geography of the small town into the secret history of the ages.

In June of 1969, at a country dance under the stars, John and Janis quarreled, as true lovers sometimes will. They drove home separately, and on the same night Judy Garland died, Janis was killed in a car wreck. John mourned for her that summer, and in September, he took poison on her grave, joining her in eternity. John and Janis were much like another pair of star-crossed young lovers, the subjects of one of that summer's biggest films. The town was too small for a movie theater, but that year, many believe, Romeo and Juliet played in Medina.

Copyright © 2004 Texas Monthly Magazine

For A Rant, Press 1. For A Rave, Press 2.

One of the joys of modern life is calling a toll-free number and listening to a menu read by a mechanical, but cheerful voice. The menu always changes frequently (according to the voice), so careful listening is essential. Evan Eisenberg has written the funniest parody of automated call system menus yet to see the light of day. If this is (fair & balanced) Luddism, so be it.

[x Slate]

Our Options Have Changed: To continue in jargon, press 1.

By Evan Eisenberg

Thank you for calling. To continue in jargon, press 1. Jos haluat jatkaa suomeksi, ole hyva ja paina 2.

Please listen closely to the following menus, as our options have changed. For technical support, press 1. For financial support, press 2. For support of the fleshy parts that jiggle during exercise, press 3. For emotional support, please hang up and call 888 HOT-LIVE.

Please note that we are currently experiencing temporary, localized service interruptions in Nome, Alaska*; Phoenix, Ariz.; Tijuana, Mexico; and all of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. If you live in one of these regions, please hang up and do not call back until we tell you. We appreciate your patience while our technicians ignore the problem.

If your appliance is less than 1 year old, press 1. If you are unmarried or are not sure, press 2.

In order to serve you better, it will be helpful for us to know which order you belong to. For Primates, press 1. For Cetacea and Proboscidea, press 2. For Jesuit or Dominican, press 3. For Knights Templar or Hospitaler, Knights of Pythias or Columbus, as well as Masons, Elks, and Kiwanis, or if you are unsure, press 4. If you are a Franciscan and have a rotary phone, please stay on the line.

Please key in the model and serial number of the product you are calling about. The model number is the series of 12 letters and digits that is visible when you push the unit away from the wall, work your head into the gap using a crowbar and No. 10 machine oil, and train a beam of ultraviolet light on the lower three centimeters of the right-hand rear surface of the appliance. If the model number is obscured by dust or cockroach detritus, wipe it with a soft, lint-free cloth soaked in a solution of ordinary rubbing alcohol, Kirschwasser, and formaldehyde. The serial number is the 37-digit number inscribed by means of laser nanotechnology on the underside of the unit and is not visible to the naked eye. When you have entered both numbers, press the pound key.

Note that at any point you may return to the previous menu by hanging up, calling again, and repeating the process until you reach the point just before the point you are at right now.

Please listen carefully to the following choices and select the one that best describes the problem you are calling about: If water is condensing on inner surfaces or leaking from under the door, press 1. If you are having trouble sending or receiving e-mail, press 2. If you are experiencing sharp, shooting pains in the left shoulder or a feeling of constriction in the chest, press 3. If you have lost your faith in a Supreme Being or any intelligible order in the universe and feel a desperate need for human contact, press 4. If you smell gas, press 5. To repeat this menu, press 6. To return to the previous menu or to a state of infantile bliss, press 7.

Please note that while you were listening to the previous menu, our options changed yet again. For Option 1, press 4. For Option 7, press 3. For Option 6, press 7. For Options 2 through 4, press 0 or hang up and call our Consumer Relations Department at (427) 555-9221. Long-distance charges may apply.

Most common problems can be resolved at home by following a simple sequence of diagnostic tests and procedures. We will now guide you through such a sequence. If you wish to skip this section, press 1, 3, and 9 simultaneously while restarting your telephone. Please note: If, while answering these questions, you see smoke or flames or if your chest is warm to the touch, hang up and call 911.

OK, let's get started.

Is the unit plugged in? If yes, press 1. If no, press 2.

Is the power switch set to "on"? If yes, press 1. If no, press 2.

Touch the condensation on the interior of the unit with your finger, then smell it. Does it smell like a dog that has been left out in the rain? If yes, press 1. If no, press 2.

Unplug your modem, power down your computer, and mix yourself a stiff drink. Drink it. Now restart your computer and plug the modem back in. Did this resolve the problem? If yes, press 1. If no, press 2.

While holding down the control and option keys, crouch on the floor, making chugging and whistling sounds. Say, "I think I can, I think I can." Continue in this manner for five minutes. Did this resolve the problem? If yes, press 1. If no, press 2.

Do you attend a church, synagogue, mosque, tabernacle, or other house of worship regularly (that is, three times a month or more)? If yes, press 1. If no, better press 1 anyway.

While remaining on this phone, use your cellular phone to call an old friend whom you haven't seen in years. Tell him or her that you've really missed him or her, and that if he or she has a problem he or she needs to talk about, you will be happy to lend a sympathetic ear. Did this resolve the problem? If yes, press 1. If no, press 2.

The diagnostic and self-help procedure is now complete. If the problem has been resolved, press 1. If the problem has been cleared up, press 2. If the problem no longer seems worth bothering with, press 3.

Thank you for calling. Goodbye.

Evan Eisenberg is the author of The Ecology of Eden and The Recording Angel, which will be reissued next spring in an expanded edition.

Another Dead-Easy To-Do List

The

- Crush Al Qaeda.

- Pacify Iraq.

- Block Iran's nuclear ambitions.

- Stabilize Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

- Restart the peace process between Palestinians and Israelis.

- Maintain the security of the world's oil supply.

- Push Arab leaders to reform without leaving them vulnerable to power grabs by terrorist fanatics.

- And do all this while making more friends for the United States in a region where most people dislike or even hate us.

Walter Russell Mead—Henry A. Kissinger Senior Fellow in US Foreign Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author, most recently, of Power, Terror, Peace, and War: America's Grand Strategy in a World at Risk (Knopf)—offered this to-do list in a review of the 9/11 Commission Report in the Boston Globe (August 29, 2004). These eight items should be the substance of the foreign policy debate between W and John Kerry. Give 'em the list in advance. Let 'em prepare. Then, hold 'em to this list of eight tasks as they tell us how they would lead this country to accomplish this foreign policy agenda. No more blather. No more flip-flopping on the so-called war on terror. I am afraid that neither W nor John Kerry could summon up a cogent plan for even one of the items, let alone all eight. We are—in the words of Bush 41—in deep doo-doo. If this is (fair & balanced) punditry, so be it.

Monday, August 30, 2004

The GOP Convention Schedule In Advance

My son, David, sent along this funny, funny parody of the GOP Convention in NYC. If this is (fair & balanced) mockery, so be it.

REPUBLICAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE CONVENTION SCHEDULE New York, NY

6:00 PM - Opening Prayer led by the Reverend Jerry Falwell

6:30 PM - Ceremonial Burning of Bill of Rights (excluding 2nd Amendment)

6:46 PM - Seminar #1: Katherine Harris on "Are Elections Really Necessary?"

7:30 PM - Announcement: Lincoln Memorial Renamed for Ronald Reagan

7:35 PM - Trent Lott - "Resegregation in the 21st Century"

7:40 PM - EPA Address #1: "Mercury: It's What's for Dinner"

8:00 PM - Voice Vote on which country to invade next

8:10 PM - Call EMTs to revive Rush Limbaugh

8:15 PM - John Ashcroft Lecture: "The Homos Are After Your Children"

8:30 PM - Round table discussion on reproductive rights (Men Only)

8:50 PM - Seminar #2: "Corporations: The Government of the Future"

9:00 PM - Condi Rice sings "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man"

9:05 PM - Phyllis Schlafly speaks on "Why Women Shouldn't Be Leaders"

9:10 PM - EPA Address #2: "Trees: The Real Cause of Forest Fires"

9:30 PM - Break for secret meetings and cash "gifts" to Cabinet Secretaries

10:00 PM - Second Prayer led by Clarence Thomas

10:15 PM - Karl Rove Lecture: "Doublespeak and Misinformation Made Simple"

10:30 PM - Rumsfeld Lecture/Demonstration: "How to Squint and Talk Macho Even When You Feel Squishy Inside"

0:40 PM - John Ashcroft Demonstration: New Mandatory Kevlar Chastity Belt

10:45 PM - GOP's Tribute to Tokenism, featuring Colin Powell and Condi Rice

10:46 PM - Ann Coulter's Tribute to "Joe McCarthy, American Patriot"

10:50 PM - Seminar #3: "Education: A Drain on Our Nation's Economy"

11:20 PM - John Ashcroft Lecture: "Evolutionists: A Dangerous New Cult"

11:30 PM - Call EMTs to revive Rush Limbaugh again

11:35 PM - Session on Blaming Hilary and Bill Clinton for Everything Wrong

11:40 PM - Newt Gingrich speaks on "The Sanctity of Marriage"

11:41 PM - Announcement: Ronald Reagan to be added to Mt. Rushmore

11:50 PM - Closing Disinformation Session led by Karl Rove

Topic: "Putting Lipstick on a Pig"

12:00 Mid - Nomination of George W. Bush as Holy Supreme Planetary Overlord

IMPORTANT NOTICE: The preceding message may be confidential or protected by the attorney-client privilege. It is not intended for transmission to, or receipt by, any unauthorized persons. If you believe that it has been sent to you in error, do not read it. Please reply to the sender that you have received the message in error. Then destroy it. Thank you.

Saturday, August 28, 2004

Posner's List

W keeps sending wacko judicial appointments to the Senate Judiciary Committee. Why doesn't he send Richard A. Posner forward? The most cerebral of the federal jurists, Posner cuts to the heart of the weaknesses of the 9/11 Commission Report. If his suggestions aren't taken to heart by the 9/11 Families and the 9/11 Commissioners, the result will be more furniture rearrangement on the deck of the Titanic. If this is (fair & balanced) analysis, so be it.

[x The New York Times]

The 9/11 Report: A Dissent

By RICHARD A. POSNER

Review of THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. Illustrated. 567 pp. W. W. Norton & Company. Paper, $10.

The idea was sound: a politically balanced, generously financed committee of prominent, experienced people would investigate the government's failure to anticipate and prevent the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Had the investigation been left to the government, the current administration would have concealed its own mistakes and blamed its predecessors. This is not a criticism of the Bush White House; any administration would have done the same.

And the execution was in one vital respect superb: the 9/11 commission report is an uncommonly lucid, even riveting, narrative of the attacks, their background and the response to them. (Norton has published the authorized edition; another edition, including reprinted news articles by reporters from The New York Times, has been published by St. Martin's, while PublicAffairs has published the staff reports and some of the testimony.)

The prose is free from bureaucratese and, for a consensus statement, the report is remarkably forthright. Though there could not have been a single author, the style is uniform. The document is an improbable literary triumph.

However, the commission's analysis and recommendations are unimpressive. The delay in the commission's getting up to speed was not its fault but that of the administration, which dragged its heels in turning over documents; yet with completion of its investigation deferred to the presidential election campaign season, the commission should have waited until after the election to release its report. That would have given it time to hone its analysis and advice.

The enormous public relations effort that the commission orchestrated to win support for the report before it could be digested also invites criticism -- though it was effective: in a poll conducted just after publication, 61 percent of the respondents said the commission had done a good job, though probably none of them had read the report. The participation of the relatives of the terrorists' victims (described in the report as the commission's ''partners'') lends an unserious note to the project (as does the relentless self-promotion of several of the members). One can feel for the families' loss, but being a victim's relative doesn't qualify a person to advise on how the disaster might have been prevented.

Much more troublesome are the inclusion in the report of recommendations (rather than just investigative findings) and the commissioners' misplaced, though successful, quest for unanimity. Combining an investigation of the attacks with proposals for preventing future attacks is the same mistake as combining intelligence with policy. The way a problem is described is bound to influence the choice of how to solve it. The commission's contention that our intelligence structure is unsound predisposed it to blame the structure for the failure to prevent the 9/11 attacks, whether it did or not. And pressure for unanimity encourages just the kind of herd thinking now being blamed for that other recent intelligence failure -- the belief that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction.

At least the commission was consistent. It believes in centralizing intelligence, and people who prefer centralized, pyramidal governance structures to diversity and competition deprecate dissent. But insistence on unanimity, like central planning, deprives decision makers of a full range of alternatives. For all one knows, the price of unanimity was adopting recommendations that were the second choice of many of the commission's members or were consequences of horse trading. The premium placed on unanimity undermines the commission's conclusion that everybody in sight was to blame for the failure to prevent the 9/11 attacks. Given its political composition (and it is evident from the questioning of witnesses by the members that they had not forgotten which political party they belong to), the commission could not have achieved unanimity without apportioning equal blame to the Clinton and Bush administrations, whatever the members actually believe.

The tale of how we were surprised by the 9/11 attacks is a product of hindsight; it could not be otherwise. And with the aid of hindsight it is easy to identify missed opportunities (though fewer than had been suspected) to have prevented the attacks, and tempting to leap from that observation to the conclusion that the failure to prevent them was the result not of bad luck, the enemy's skill and ingenuity or the difficulty of defending against suicide attacks or protecting an almost infinite array of potential targets, but of systemic failures in the nation's intelligence and security apparatus that can be corrected by changing the apparatus.

That is the leap the commission makes, and it is not sustained by the report's narrative. The narrative points to something different, banal and deeply disturbing: that it is almost impossible to take effective action to prevent something that hasn't occurred previously. Once the 9/11 attacks did occur, measures were taken that have reduced the likelihood of a recurrence. But before the attacks, it was psychologically and politically impossible to take those measures. The government knew that Al Qaeda had attacked United States facilities and would do so again. But the idea that it would do so by infiltrating operatives into this country to learn to fly commercial aircraft and then crash such aircraft into buildings was so grotesque that anyone who had proposed that we take costly measures to prevent such an event would have been considered a candidate for commitment. No terrorist had hijacked an American commercial aircraft anywhere in the world since 1986. Just months before the 9/11 attacks the director of the Defense Department's Defense Threat Reduction Agency wrote: ''We have, in fact, solved a terrorist problem in the last 25 years. We have solved it so successfully that we have forgotten about it; and that is a treat. The problem was aircraft hijacking and bombing. We solved the problem. . . . The system is not perfect, but it is good enough. . . . We have pretty much nailed this thing.'' In such a climate of thought, efforts to beef up airline security not only would have seemed gratuitous but would have been greatly resented because of the cost and the increased airport congestion.

The problem isn't just that people find it extraordinarily difficult to take novel risks seriously; it is also that there is no way the government can survey the entire range of possible disasters and act to prevent each and every one of them. As the commission observes, ''Historically, decisive security action took place only after a disaster had occurred or a specific plot had been discovered.'' It has always been thus, and probably always will be. For example, as the report explains, the 1993 truck bombing of the World Trade Center led to extensive safety improvements that markedly reduced the toll from the 9/11 attacks; in other words, only to the slight extent that the 9/11 attacks had a precedent were significant defensive steps taken in advance.

The commission's contention that ''the terrorists exploited deep institutional failings within our government'' is overblown. By the mid-1990's the government knew that Osama bin Laden was a dangerous enemy of the United States. President Clinton and his national security adviser, Samuel Berger, were so concerned that Clinton, though ''warned in the strongest terms'' by the Secret Service and the C.I.A. that ''visiting Pakistan would risk the president's life,'' did visit that country (flying in on an unmarked plane, using decoys and remaining only six hours) and tried unsuccessfully to enlist its cooperation against bin Laden. Clinton authorized the assassination of bin Laden, and a variety of means were considered for achieving this goal, but none seemed feasible. Invading Afghanistan to pre-empt future attacks by Al Qaeda was considered but rejected for diplomatic reasons, which President Bush accepted when he took office and which look even more compelling after the trouble we've gotten into with our pre-emptive invasion of Iraq. The complaint that Clinton was merely ''swatting at flies,'' and the claim that Bush from the start was determined to destroy Al Qaeda root and branch, are belied by the commission's report. The Clinton administration envisaged a campaign of attrition that would last three to five years, the Bush administration a similar campaign that would last three years. With an invasion of Afghanistan impracticable, nothing better was on offer. Almost four years after Bush took office and almost three years after we wrested control of Afghanistan from the Taliban, Al Qaeda still has not been destroyed.

It seems that by the time Bush took office, ''bin Laden fatigue'' had set in; no one had practical suggestions for eliminating or even substantially weakening Al Qaeda. The commission's statement that Clinton and Bush had been offered only a ''narrow and unimaginative menu of options for action'' is hindsight wisdom at its most fatuous. The options considered were varied and imaginative; they included enlisting the Afghan Northern Alliance or other potential tribal allies of the United States to help kill or capture bin Laden, an attack by our Special Operations forces on his compound, assassinating him by means of a Predator drone aircraft or coercing or bribing the Taliban to extradite him. But for political or operational reasons, none was feasible.

It thus is not surprising, perhaps not even a fair criticism, that the new administration treaded water until the 9/11 attacks. But that's what it did. Bush's national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, ''demoted'' Richard Clarke, the government's leading bin Laden hawk and foremost expert on Al Qaeda. It wasn't technically a demotion, but merely a decision to exclude him from meetings of the cabinet-level ''principals committee'' of the National Security Council; he took it hard, however, and requested a transfer from the bin Laden beat to cyberterrorism. The committee did not discuss Al Qaeda until a week before the 9/11 attacks. The new administration showed little interest in exploring military options for dealing with Al Qaeda, and Donald Rumsfeld had not even gotten around to appointing a successor to the Defense Department's chief counterterrorism official (who had left the government in January) when the 9/11 attacks occurred.

I suspect that one reason, not mentioned by the commission, for the Bush administration's initially tepid response to the threat posed by Al Qaeda is that a new administration is predisposed to reject the priorities set by the one it's succeeding. No doubt the same would have been true had Clinton been succeeding Bush as president rather than vice versa.

Before the commission's report was published, the impression was widespread that the failure to prevent the attacks had been due to a failure to collate bits of information possessed by different people in our security services, mainly the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. And, indeed, had all these bits been collated, there would have been a chance of preventing the attacks, though only a slight one; the best bits were not obtained until late in August 2001, and it is unrealistic to suppose they could have been integrated and understood in time to detect the plot.

The narrative portion of the report ends at Page 338 and is followed by 90 pages of analysis and recommendations. I paused at Page 338 and asked myself what improvements in our defenses against terrorist groups like Al Qaeda are implied by the commission's investigative findings (as distinct from recommendations that the commission goes on to make in the last part of the report). The list is short:

(1) Major buildings should have detailed evacuation plans and the plans should be communicated to the occupants.

(2) Customs officers should be alert for altered travel documents of Muslims entering the United States; some of the 9/11 hijackers might have been excluded by more careful inspections of their papers. Biometric screening (such as fingerprinting) should be instituted to facilitate the creation of a comprehensive database of suspicious characters. In short, our borders should be made less porous.

(3) Airline passengers and baggage should be screened carefully, cockpit doors secured and override mechanisms installed in airliners to enable a hijacked plane to be controlled from the ground.

(4) Any legal barriers to sharing information between the C.I.A. and the F.B.I. should be eliminated.

(5) More Americans should be trained in Arabic, Farsi and other languages in widespread use in the Muslim world. The commission remarks that in 2002, only six students received undergraduate degrees in Arabic from colleges in the United States.

(6) The thousands of federal agents assigned to the ''war on drugs,'' a war that is not only unwinnable but probably not worth winning, should be reassigned to the war on international terrorism.

(7) The F.B.I. appears from the report to be incompetent to combat terrorism; this is the one area in which a structural reform seems indicated (though not recommended by the commission). The bureau, in excessive reaction to J. Edgar Hoover's freewheeling ways, has become afflicted with a legalistic mind-set that hinders its officials from thinking in preventive rather than prosecutorial terms and predisposes them to devote greater resources to drug and other conventional criminal investigations than to antiterrorist activities. The bureau is habituated to the leisurely time scale of criminal investigations and prosecutions. Information sharing within the F.B.I., let alone with other agencies, is sluggish, in part because the bureau's field offices have excessive autonomy and in part because the agency is mysteriously unable to adopt a modern communications system. The F.B.I. is an excellent police department, but that is all it is. Of all the agencies involved in intelligence and counterterrorism, the F.B.I. comes out worst in the commission's report.

Progress has been made on a number of items on my list. There have been significant improvements in border control and aircraft safety. The information ''wall'' was removed by the USA Patriot Act, passed shortly after 9/11, although legislation may not have been necessary, since, as the commission points out, before 9/11 the C.I.A. and the F.B.I. exaggerated the degree to which they were forbidden to share information. This was a managerial failure, not an institutional one. Efforts are under way on (5) and (6), though powerful political forces limit progress on (6). Oddly, the simplest reform -- better building-evacuation planning -- has lagged.

The only interesting item on my list is (7). The F.B.I.'s counterterrorism performance before 9/11 was dismal indeed. Urged by one of its field offices to seek a warrant to search the laptop of Zacarias Moussaoui (a candidate hijacker-pilot), F.B.I. headquarters refused because it thought the special court that authorizes foreign intelligence surveillance would decline to issue a warrant -- a poor reason for not requesting one. A prescient report from the Arizona field office on flight training by Muslims was ignored by headquarters. There were only two analysts on the bin Laden beat in the entire bureau. A notice by the director, Louis J. Freeh, that the bureau focus its efforts on counterterrorism was ignored.

So what to do? One possibility would be to appoint as director a hard-nosed, thick-skinned manager with a clear mandate for change -- someone of Donald Rumsfeld's caliber. (His judgment on Iraq has been questioned, but no one questions his capacity to reform a hidebound government bureaucracy.) Another would be to acknowledge the F.B.I.'s deep-rooted incapacity to deal effectively with terrorism, and create a separate domestic intelligence agency on the model of Britain's Security Service (M.I.5). The Security Service has no power of arrest. That power is lodged in the Special Branch of Scotland Yard, and if we had our own domestic intelligence service, modeled on M.I.5, the power of arrest would be lodged in a branch of the F.B.I. As far as I know, M.I.5 and M.I.6 (Britain's counterpart to the C.I.A.) work well together. They have a common culture, as the C.I.A. and the F.B.I. do not. They are intelligence agencies, operating by surveillance rather than by prosecution. Critics who say that an American equivalent of M.I.5 would be a Gestapo understand neither M.I.5 nor the Gestapo.

Which brings me to another failing of the 9/11 commission: American provinciality. Just as we are handicapped in dealing with Islamist terrorism by our ignorance of the languages, cultures and history of the Muslim world, so we are handicapped in devising effective antiterrorist methods by our reluctance to consider foreign models. We shouldn't be embarrassed to borrow good ideas from nations with a longer experience of terrorism than our own. The blows we have struck against Al Qaeda's centralized organization may deflect Islamist terrorists from spectacular attacks like 9/11 to retail forms like car and truck bombings, assassinations and sabotage. If so, Islamist terrorism may come to resemble the kinds of terrorism practiced by the Irish Republican Army and Hamas, with which foreign nations like Britain and Israel have extensive experience. The United States remains readily penetrable by Islamist terrorists who don't even look or sound Middle Eastern, and there are Qaeda sleeper cells in this country. All this underscores the need for a domestic intelligence agency that, unlike the F.B.I., is effective.

Were all the steps that I have listed fully implemented, the probability of another terrorist attack on the scale of 9/11 would be reduced -- slightly. The measures adopted already, combined with our operation in Afghanistan, have undoubtedly reduced that probability, and the room for further reduction probably is small. We and other nations have been victims of surprise attacks before; we will be again.

They follow a pattern. Think of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the Tet offensive in Vietnam in 1968. It was known that the Japanese might attack us. But that they would send their carrier fleet thousands of miles to Hawaii, rather than just attack the nearby Philippines or the British and Dutch possessions in Southeast Asia, was too novel and audacious a prospect to be taken seriously. In 1968 the Vietnamese Communists were known to be capable of attacking South Vietnam's cities. Indeed, such an assault was anticipated, though not during Tet (the Communists had previously observed a truce during the Tet festivities) and not on the scale it attained. In both cases the strength and determination of the enemy were underestimated, along with the direction of his main effort. In 2001 an attack by Al Qaeda was anticipated, but it was anticipated to occur overseas, and the capability and audacity of the enemy were underestimated. (Note in all three cases a tendency to underestimate non-Western foes -- another aspect of provinciality.)

Anyone who thinks this pattern can be changed should read those 90 pages of analysis and recommendations that conclude the commission's report; they come to very little. Even the prose sags, as the reader is treated to a barrage of bromides: ''the American people are entitled to expect their government to do its very best,'' or ''we should reach out, listen to and work with other countries that can help'' and ''be generous and caring to our neighbors,'' or we should supply the Middle East with ''programs to bridge the digital divide and increase Internet access'' -- the last an ironic suggestion, given that encrypted e-mail is an effective medium of clandestine communication. The ''hearts and minds'' campaign urged by the commission is no more likely to succeed in the vast Muslim world today than its prototype was in South Vietnam in the 1960's.

The commission wants criteria to be developed for picking out which American cities are at greatest risk of terrorist attack, and defensive resources allocated accordingly -- this to prevent every city from claiming a proportional share of those resources when it is apparent that New York and Washington are most at risk. Not only do we lack the information needed to establish such criteria, but to make Washington and New York impregnable so that terrorists can blow up Los Angeles or, for that matter, Kalamazoo with impunity wouldn't do us any good.

The report states that the focus of our antiterrorist strategy should not be ''just 'terrorism,' some generic evil. This vagueness blurs the strategy. The catastrophic threat at this moment in history is more specific. It is the threat posed by Islamist terrorism.'' Is it? Who knows? The menace of bin Laden was not widely recognized until just a few years before the 9/11 attacks. For all anyone knows, a terrorist threat unrelated to Islam is brewing somewhere (maybe right here at home -- remember the Oklahoma City bombers and the Unabomber and the anthrax attack of October 2001) that, given the breathtakingly rapid advances in the technology of destruction, will a few years hence pose a greater danger than Islamic extremism. But if we listen to the 9/11 commission, we won't be looking out for it because we've been told that Islamist terrorism is the thing to concentrate on.

Illustrating the psychological and political difficulty of taking novel threats seriously, the commission's recommendations are implicitly concerned with preventing a more or less exact replay of 9/11. Apart from a few sentences on the possibility of nuclear terrorism, and of threats to other modes of transportation besides airplanes, the broader range of potential threats, notably those of bioterrorism and cyberterrorism, is ignored.

Many of the commission's specific recommendations are sensible, such as that American citizens should be required to carry biometric passports. But most are in the nature of more of the same -- more of the same measures that were implemented in the wake of 9/11 and that are being refined, albeit at the usual bureaucratic snail's pace. If the report can put spurs to these efforts, all power to it. One excellent recommendation is reducing the number of Congressional committees, at present in the dozens, that have oversight responsibilities with regard to intelligence. The stated reason for the recommendation is that the reduction will improve oversight. A better reason is that with so many committees exercising oversight, our senior intelligence and national security officials spend too much of their time testifying.

The report's main proposal -- the one that has received the most emphasis from the commissioners and has already been endorsed in some version by both presidential candidates -- is for the appointment of a national intelligence director who would knock heads together in an effort to overcome the reluctance of the various intelligence agencies to share information. Yet the report itself undermines this proposal, in a section titled ''The Millennium Exception.'' ''In the period between December 1999 and early January 2000,'' we read, ''information about terrorism flowed widely and abundantly.'' Why? Mainly ''because everyone was already on edge with the millennium and possible computer programming glitches ('Y2K').'' Well, everyone is now on edge because of 9/11. Indeed, the report suggests no current impediments to the flow of information within and among intelligence agencies concerning Islamist terrorism. So sharing is not such a problem after all. And since the tendency of a national intelligence director would be to focus on the intelligence problem du jour, in this case Islamist terrorism, centralization of the intelligence function could well lead to overconcentration on a single risk.

The commission thinks the reason the bits of information that might have been assembled into a mosaic spelling 9/11 never came together in one place is that no one person was in charge of intelligence. That is not the reason. The reason or, rather, the reasons are, first, that the volume of information is so vast that even with the continued rapid advances in data processing it cannot be collected, stored, retrieved and analyzed in a single database or even network of linked databases. Second, legitimate security concerns limit the degree to which confidential information can safely be shared, especially given the ever-present threat of moles like the infamous Aldrich Ames. And third, the different intelligence services and the subunits of each service tend, because information is power, to hoard it. Efforts to centralize the intelligence function are likely to lengthen the time it takes for intelligence analyses to reach the president, reduce diversity and competition in the gathering and analysis of intelligence data, limit the number of threats given serious consideration and deprive the president of a range of alternative interpretations of ambiguous and incomplete data -- and intelligence data will usually be ambiguous and incomplete.

The proposal begins to seem almost absurd when one considers the variety of our intelligence services. One of them is concerned with designing and launching spy satellites; another is the domestic intelligence branch of the F.B.I.; others collect military intelligence for use in our conflicts with state actors like North Korea. There are 15 in all. The national intelligence director would be in continuous conflict with the attorney general, the secretary of defense, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the secretary of homeland security and the president's national security adviser. He would have no time to supervise the organizational reforms that the commission deems urgent.

The report bolsters its proposal with the claim that our intelligence apparatus was designed for fighting the cold war and so can't be expected to be adequate to fighting Islamist terrorism. The cold war is depicted as a conventional military face-off between the United States and the Soviet Union and hence a 20th-century relic (the 21st century is to be different, as if the calendar drove history). That is not an accurate description. The Soviet Union operated against the United States and our allies mainly through subversion and sponsored insurgency, and it is not obvious why the apparatus developed to deal with that conduct should be thought maladapted for dealing with our new enemy.

The report notes the success of efforts to centralize command of the armed forces, and to reduce the lethal rivalries among the military services. But there is no suggestion that the national intelligence director is to have command authority.

The central-planning bent of the commission is nowhere better illustrated than by its proposal to shift the C.I.A.'s paramilitary operations, despite their striking success in the Afghanistan campaign, to the Defense Department. The report points out that ''the C.I.A. has a reputation for agility in operations,'' whereas the reputation of the military is ''for being methodical and cumbersome.'' Rather than conclude that we are lucky to have both types of fighting capacity, the report disparages ''redundant, overlapping capabilities'' and urges that ''the C.I.A.'s experts should be integrated into the military's training, exercises and planning.'' The effect of such integration is likely to be the loss of the ''agility in operations'' that is the C.I.A.'s hallmark. The claim that we ''cannot afford to build two separate capabilities for carrying out secret military operations'' makes no sense. It is not a question of building; we already have multiple such capabilities -- Delta Force, Marine reconnaissance teams, Navy Seals, Army Rangers, the C.I.A.'s Special Activities Division. Diversity of methods, personnel and organizational culture is a strength in a system of national security; it reduces risk and enhances flexibility.

What is true is that 15 agencies engaged in intelligence activities require coordination, notably in budgetary allocations, to make sure that all bases are covered. Since the Defense Department accounts for more than 80 percent of the nation's overall intelligence budget, the C.I.A., with its relatively small budget (12 percent of the total), cannot be expected to control the entire national intelligence budget. But to layer another official on top of the director of central intelligence, one who would be in a constant turf war with the secretary of defense, is not an appealing solution. Since all executive power emanates from the White House, the national security adviser and his or her staff should be able to do the necessary coordinating of the intelligence agencies. That is the traditional pattern, and it is unlikely to be bettered by a radically new table of organization.

So the report ends on a flat note. But one can sympathize with the commission's problem. To conclude after a protracted, expensive and much ballyhooed investigation that there is really rather little that can be done to reduce the likelihood of future terrorist attacks beyond what is being done already, at least if the focus is on the sort of terrorist attacks that have occurred in the past rather than on the newer threats of bioterrorism and cyberterrorism, would be a real downer -- even a tad un-American. Americans are not fatalists. When a person dies at the age of 95, his family is apt to ascribe his death to a medical failure. When the nation experiences a surprise attack, our instinctive reaction is not that we were surprised by a clever adversary but that we had the wrong strategies or structure and let's change them and then we'll be safe. Actually, the strategies and structure weren't so bad; they've been improved; further improvements are likely to have only a marginal effect; and greater dangers may be gathering of which we are unaware and haven't a clue as to how to prevent.

Judge Richard A. Posner

serves on the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, is a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School and is the author of the forthcoming book Catastrophe: Risk and Response.

Copyright © 2004 The New York Times Company

Friday, August 27, 2004

The REAL Fab 5

Thursday, August 26, 2004

My Kind Of Women

US Olympic Team—Women's Soccer—Mia Hamm (center kneeling) and Brianna Scurry (red goalie jersey)

Brandi Chastain, Joy Fawcett, Kristine Lilly, Julie Foudy, Mia Hamm, Brianna Scurry, Abby Wambach, Cat Reddick, Shannon Boxx, Kylie Bivens, Heather O’Reilly, Lindsay Tarpley, Devvyn Hawkins, Leslie Osborne, Nandi Pryce, and Lori Chalupny. Don't forget their coach: April Heinrichs. W ought to send these women to Iraq. Their eyes were unbelievable. Nothing was going to stop them. The broadcast of the Gold Medal match with Brazil on Univision was incredible.

GOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOAL!

These women took on the world and played the right way (as Olympic Coach Larry Brown of the Men's Basketball Team would put it) and they played hard. Not dirty, but they gave as good as they got from a savvy international soccer team. If this is (fair & balanced) admiration, so be it.

Wednesday, August 25, 2004

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, MD—RIP

I first confronted death and dying with the terminal cancer illness of my father, Bob Sapper. My father faced death bravely and I pray for the grace under pressure to do the same. If this is (fair & balanced) thanatology, so be it.

[x NYTimes]

Dr. Kübler-Ross, Who Changed Perspectives on Death, Dies at 78

By HOLCOMB B. NOBLE

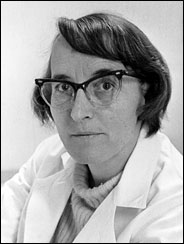

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in 1970.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, the psychiatrist whose pioneering work in counseling terminally ill patients helped to revolutionize the care of the dying, enabling people all over the world to die more peacefully and with greater dignity, died Tuesday at her home in Scottsdale, Ariz. She was 78.

Family members told The Associated Press she died of natural causes.

A series of strokes had debilitated her, but as she neared her own death she appeared to accept it, as she had tried to help so many others to do. She seemed ready to experience death, saying: "I'm going to dance in all the galaxies."

Dr. Kübler-Ross was credited with ending centuries-old taboos in Western culture against openly discussing and studying death. She set in motion techniques of care directed at making death less dehumanizing and psychologically painful for patients, for the professionals who attend them and the loved ones who survive them.

She accomplished this largely through her writings, especially the 1969 best-seller, "On Death and Dying," which is still in print around the world; through her lectures and tape recordings; her research into what she described as the five stages of death, based on thousands of interviews with patients and health-care professionals and through her own groundbreaking work in counseling dying patients.

She was a powerful intellectual force behind the creation of the hospice system in the United States through which special care is now provided for the terminally ill. And she helped to turn thanatology, the study of physical, psychological and social problems associated with dying, into an accepted medical discipline.

"Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was a true pioneer in raising the awareness among the physician community and the general public about the important issues surrounding death, dying and bereavement," said Dr. Percy Wooten, president of the American Medical Association. He said much of her work was a basis for the A.M.A.'s attempts to encourage the medical profession to improve the care patients received at the end of life.

The A.M.A was one of her early supporters, though many of its members at first vigorously opposed her and attempted to ostracize her.

Florence Wald of the Yale School of Nursing said that before her research "doctors and nurses had been simply avoiding the problem of death and focusing on patients who could get better." She said, Dr. Kübler-Ross's "willingness and skill in getting patients to talk about their impending death in ways that helped them set a profoundly important example for nurses everywhere."

In the later part of her career, she embarked on research to verify the existence of life after death, conducting, with others, thousands of interviews with people who recounted near-death experiences, particularly those declared clinically dead by medical authorities but who were then revived. Her prestige generated widespread interest in such research and attracted followers who considered her a saint.

But this work aroused deep skepticism in medical and scientific circles and damaged her reputation. Her claims that she had evidence of an afterlife saddened many of her colleagues, some of whom believed that she had abandoned rigorous science and had succumbed to her own fears of death.

"For years I have been stalked by a bad reputation," she said in her 1997 autobiography "The Wheel of Life: A Memoir of Living and Dying." "Actually, I have been pursued by people who have regarded me as the Death and Dying Lady. They believe that having spent more than three decades in research into death and life after death qualifies me as an expert on the subject. I think they miss the point. The only incontrovertible fact of my work is the importance of life. I always say that death can be one of the greatest experiences ever. If you live each day of your life right, then you have nothing to fear."

Whatever scientists feel about her view of life after death, they continue to be influenced by her methods of caring for the terminally ill. Before "On Death and Dying," terminally ill patients were often left to face death in a miasma of loneliness and fear because doctors, nurses and families were generally poorly equipped to deal with death.

Dr. Kübler-Ross changed all that. By the 1980's, the study of the processes and treatment of dying became a routine part of medical and health-care education in the United States. "Death and Dying" became an indispensable manual, both for professionals and for family members. Many doctors and counselors have relied on it to learn to cope themselves with the loss of their patients, and face their own mortality.

Her early childhood may have been the "instigator," as she put it, in shaping her career. Weighing barely two pounds at birth, she was the first of triplets born to Ernst and Emma Villiger Kübler on July 8, 1926 in Zurich, Switzerland.

She might not have lived, she wrote, "If it had not been for the determination of my mother," who thought a sick child must be kept close to her parents in the intimate environment of the home, not at a hospital.

But there were moments in her childhood in a farm village when she saw death as both moving and frightening. A friend of her father who was dying after a fall from a tree invited neighbors into his home and, with no sign of fear as death approached, asked them to help his wife and children save their farm. "My last visit with him filled me with great pride and joy," she said.

Later, a schoolmate died of meningitis. Relatives or friends of the child were with her night and day, and when she died, her school was closed and half the village attended the funeral.

"There was a feeling of solidarity, of common tragedy shared," Dr. Kübler-Ross said. By contrast, when she was 5, she was "caged" in a hospital with pneumonia, allowed to see her parents only through a glass window, with "no familiar voice, touch, odor, not even a familiar toy." She believed that only her vivid dreams and fantasies enabled her to survive.

By the sixth grade, she wanted to be a physician. But her father, she said, saw only two possibilities in life: "his way and the wrong way." "Elisabeth," he said, "you will work in my office. I need an intelligent secretary."

"No thank you," she said, and her father's face flushed with anger.

"Then you can spend the rest of your life as a maid."

"That's all right with me," she replied.

When she finished school, she worked at various jobs and began her lifelong involvement with humanitarian causes. She volunteered at Zurich's largest hospital to help refugees from Nazi Germany. And when World War II ended, she hitchhiked through nine war-shattered countries, helping to open first-aid posts and working on reconstruction projects, as a cook, mason and roofer.

In Poland, her visit to the Majdanek concentration camp narrowed her professional goal: she would become a psychiatrist to help people cope with death.

Back in Switzerland, she enrolled at the University of Zurich medical school, receiving her degree in 1957. Within a year she had come to the United States; married Dr. Emanuel K. Ross, an American neuropathologist she met at the University of Zurich; begun her internship at Community Hospital in Glen Cove, N.Y., and become a research fellow at Manhattan State Hospital on Ward's Island in New York City.

There she was appalled by what she called routine treatment of dying patients: "They were shunned and abused," she wrote, "sometimes kept in hot tubs with water up to their necks and left for 24 hours at a time."

After badgering her supervisors, she was allowed to develop programs under which the patients were given individual care and counseling.

In 1962, she became a teaching fellow at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. A small woman, who spoke with a heavy German accent and was shy, despite extraordinary inner self-confidence, she was highly nervous when asked to fill in for a popular professor and master lecturer. She found the medical students rude, paying her scant attention and talking to one another as she spoke.

But the hall became noticeably quieter when she brought out a 16-year-old patient who was dying of leukemia, and asked the students to interview her. Now it was they who seemed nervous. When she prodded them, they would ask the patient about her blood counts, chemotherapy or other clinical matters.

Finally, the teenager exploded in anger, and began posing her own questions: What was it like not to be able to dream about the high-school prom? Or going on a date? Or growing up? "Why," she demanded, "won't people tell you the truth?" When the lecture ended, many students had been moved to tears.

"Now you're acting like human beings, instead of scientists," Dr. Kübler-Ross said.

Her lectures began to draw standing-room-only audiences of medical and theology students, clergymen and social workers — but few doctors.

In 1965, she became an assistant professor in psychiatry at the University of Chicago Medical School, where a group of theology students approached her for help in studying death. She suggested a series of conversations with dying patients, who would be asked their thoughts and feelings; the patients would teach the professionals. At first, staff doctors objected.

Avoiding the subject entirely, particularly when treating the young, physicians and therapists would meet a dying child's questions with comments like, "Take your medicine, and you'll get well," Dr. Kübler-Ross said.

In "On Death and Dying," her account of the seminars on dying that she conducted at Chicago, she asked: What happens to a society when "its young medical student is admired for his research and laboratory work while he is at a loss for words when a patient asks him a simple question?"

She said children instinctively knew that the answers they received about their prognoses were lies and this made them feel punished and alone. Children were often better at coping with imminent death than adults, she said, and told of 9-year-old Jeff, who though weakened with leukemia asked to leave the hospital and go home and ride his bicycle one more time.

The boy's father, tears in his eyes, put the training wheels back on the bike at the boy's request, and his mother was kept by Dr. Kübler-Ross from helping him ride. Jeff came back after a spin around the block in final triumph, the psychiatrist said, and then gave the bicycle to his younger brother.

To bring public pressure for change in hospitals' treatment of the dying, she agreed to a request by Life magazine in 1965 to interview one of her seminar patients, Eva, who felt her doctors had treated her coldly and arrogantly. The Life article prompted one physician, encountering Dr. Kübler-Ross in a hospital corridor, to remark: "Are you looking for your next patient for publicity."

The hospital said it wanted not to be famous for its dying patients but rather for those it saved, and ordered its doctors not to cooperate further. The lecture hall for her next seminar was empty.

"Although humiliated," she said, "I knew they could not stop everything that had been put in motion by the press." The hospital switchboard was overwhelmed with calls in reaction to the Life article; mail piled up and she was invited to speak at other colleges and universities.

Not that this helped Eva much. Dr. Kübler-Ross said she looked in on her years later and found her lying naked on a hospital bed, unable to speak, with an overhead light glaring in her eyes. "She pressed my hand as a way of saying hello, and pointed her other hand up toward the ceiling. I turned the light off and asked a nurse to cover Eva. Unbelievably, the nurse hesitated, and asked, `Why?' " Dr. Kübler-Ross covered the patient herself. Eva died the next day.

"The way she died, cold and alone, was something I could not tolerate," Dr. Kübler-Ross said. Gradually, the medical profession came to accept her new approaches to treating the terminally ill.

From her patient interviews, Dr. Kübler-Ross identified five stages many patients go through in confronting their own deaths. Often denial is the first stage, when the patient is unwilling or unable to face his predicament. As his condition worsens and denial is impossible, the patient displays anger — the "why me?" stage. This is followed by a bargaining period ("Yes, I'm going to die, but if I diet and exercise, can I do it later?"). When the patient sees that bargaining won't work, depression often sets in. The final stage is acceptance, a passive period in which the patient is ready to let go.

Not all dying patients follow the same progression, said Dr. Kübler-Ross, but most experience two or more of these stages. Moreover, she found, people who are experiencing traumatic change in their lives, such as a divorce, often experience similar stages.

Another conclusion she reached was that an untraumatic acceptance of death came easiest for those who could look back and feel they had lived honestly and felt they had not wasted their lives.

In later years, Dr. Kübler-Ross's insistence that she could prove the existence of a serene afterlife drew fire from scientists and many lecture appearances were canceled. The center she built in California in the late 1970's burned, and the police suspected arson. She set up another center in 1984 in Virginia to care for children with AIDS; that center also was burned, in 1994, and arson was again suspected. After the second fire, she moved to Scottsdale, Ariz., to be near her son, Kenneth, a freelance photographer.

That year, when Dr. Ross was dying, he moved to a condominium in Scottsdale near Dr. Kübler-Ross, even though they were divorced. She and their son, Kenneth, cared for him. In addition to the son, Dr. Kübler-Ross is survived by a daughter, Barbara Ross, a clinical psychologist, of Wausau, Wis.; her brother Ernst, of Surrey, England; and her triplet sisters, Erika and Eva of Basel, Switzerland.

As Dr. Kübler-Ross awaited her own death, in a darkened room at her home in Arizona, she acknowledged that she was in pain and ready for her life to end. But she said, "I know beyond a shadow of a doubt that there is no death the way we understood it. The body dies, but not the soul."

Copyright © 2004 The New York Times Company

ANOTHER Modest Proposal

Another 527 Group? How about Dummies For Bush? W has self-defined himself as a dumbass; stupid, but cunning. His malapropisms abound and astound. W is proud of his mispronunciation of nuclear. In his mind (using the term loosely), there is honor in mediocrity. Frat-boy jocularity passes for wit. I hate to think what Dr. Samuel Johnson would say of him if W had been born in another place (London) at another time (early 18th century). The good Dr. Johnson would dismiss W as a babbling idiot. Now, who would join (and support) Dummies For Bush? They're everywhere. Anyone with a W bumper strip or a W lapel pin is a prime candidate. Not only does W self-define, but all of the Bush supporters self define themselves as dummies. This cognitive underclass elected W in 2000. May the Almighty have mercy on our souls if W is given 4 more years by them. If this is (fair & balanced) dismay, so be it.

[x Jerusalem Post]

In praise of mediocrity

by Bret Stephens

Friday, July 26, 2002 -- Poor Roman Hruska. In April 1970, the Nebraska Republican took to the floor of the Senate to defend the nomination of G. Harrold Carswell, a federal judge on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, to the United States Supreme Court. It was a trying time. Questions had been raised about Carswell's commitment to civil rights. Betty Friedan testified that he was a sexist. The judge's rulings tended to be overturned on appeal, so he was considered an intellectual lightweight. And the administration was hurting, too. A defeat for Carswell would be the second consecutive rejection by the Senate of a Nixon Supreme Court nominee (the first was Clement Haynsworth), something the president could ill afford in the run-up to the midterm elections.

In this atmosphere, Hruska delivered the remark that would become his epitaph. "It has been held against this nominee that he is mediocre," he told the Senate chamber. "Even if he is mediocre there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren't they, and a little chance? We can't have all Brandeises, Cardozos and Frankfurters and stuff like that there."

Needless to say, Hruska's defense did not do much to help Carswell, who went down in a 51-45 vote and was later indicted for soliciting a male prostitute in a Florida shopping mall. Hruska's reputation fared little better. At the time of the nomination, the Nebraskan had been a senator for 16 years and held seats both on the appropriations and the judiciary committee, where he was known by colleagues as a "workhorse," a "senator's senator," and a contender for the GOP leadership. Yet becoming the champion of the mediocre man also made him the epitome of one, and he never lived it down. When he died, in 1999, every obituary of him reprinted the comment, about which Hruska himself was said to be much abashed.